HONDA CB200

You can go home again. Just not very rapidly.

PETER JONES

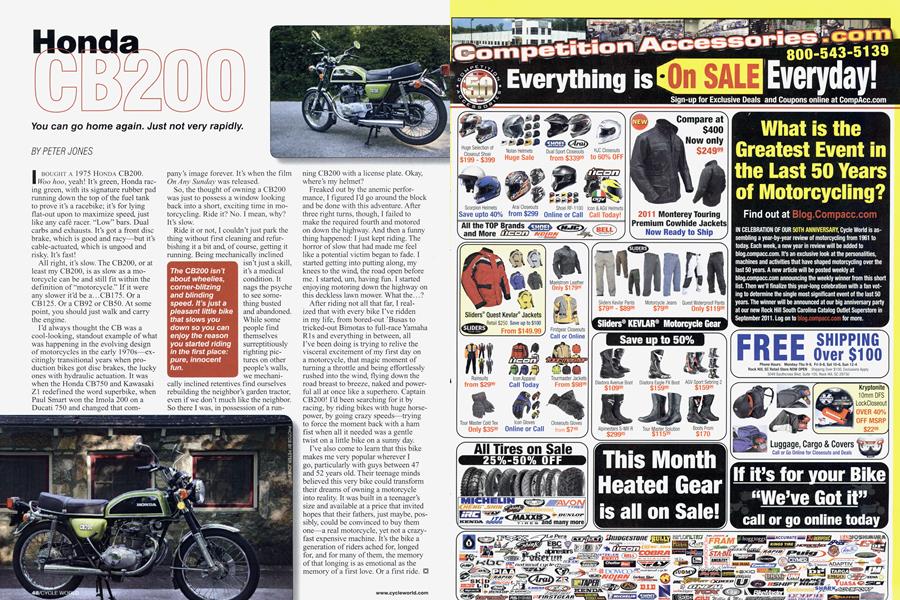

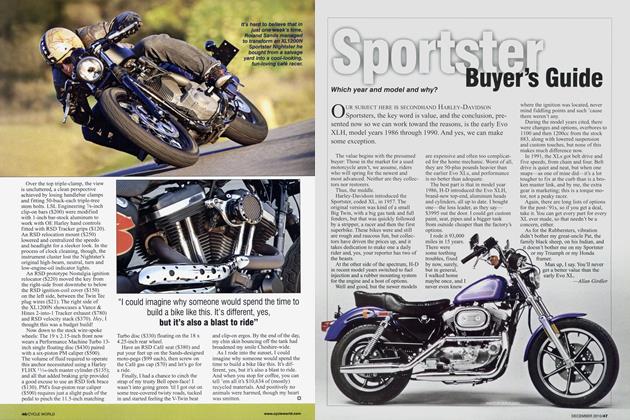

I BOUGHT A 1975 HONDA CB200. Woo hoo, yeah! It's green, Honda raeing green, with its signature rubber pad running down the top of the fuel tank to prove it's a racebike; it's for lying flat-out upon to maximize speed, just like any café racer. "Low" bars. Dual carbs and exhausts. It's got a front disc brake, which is good and racy—but it's cable-actuated, which is ungood and risky. It's fast!

All right, it's slow. The CB200, or at least my CB200, is as slow as a mo torcycle can be and still fit within the definition of "motorcycle." If it were any slower it'd be a.. .CB175. Or a CB125. Or a CB92 or CB5O. At some point, you should just walk and carry the engine.

I'd always thought the CB was a cool-looking, standout example of what was happening in the evolving design of motorcycles in the early 1 970s-excitingly transitional years when pro duction bikes got disc brakes, the lucky ones with hydraulic actuation. It was when the Honda CB750 and Kawasaki Zi redefined the word superbike, when Paul Smart won the Imola 200 on a Ducati 750 and changed that cornpany's image forever. It's when the film On Any Sunday was released.

So, the thought of owning a CB200 was just to possess a window looking back into a short, exciting time in mo torcycling. Ride it? No. I mean, why? It's slow.

Ride it or not, I couldn't just park the thing without first cleaning and refur bishing it a bit and, of course, getting it running. Being mechanically inclined isn't just a skill, it's a medical condition. It nags the psyche to see some thing busted and abandoned. While some people find themselves surreptitiously righting pic tures on other people's walls, we mechani cally inclined retentives find ourselves rebuilding the neighbor's garden tractor, even if we don't much like the neighbor. So there I was, in possession of a runfling CB200 with a license plate. Okay, where's my helmet?

Freaked out by the anemic perfOr mance, I figured I'd go around the block and be done with this adventure. After three right turns, though, I failed to make the required fourth and motored on down the highway. And then a funny thing happened: I just kept riding. The horror of slow that had made me feel like a potential victim began to fade. I started getting into putting along, my knees to the wind, the road open before me. I started, um, having fun. I started enjoying motoring down the highway on this deckless lawn mower. What the...?

After riding not all that far, I real ized that with every bike I've ridden in my life, from bored-out `Busas to tricked-out Bimotas to full-race Yamaha Ri s and everything in between, all I've been doing is trying to relive the visceral excitement of my first day on a motorcycle, that magic moment of turning a throttle and being effortlessly rushed into the wind, flying down the road breast to breeze, naked and power ful all at once like a superhero. Captain CB200! I'd been searching for it by racing, by riding bikes with huge horse power, by going crazy speeds-trying to force the moment back with a ham fist when all it needed was a gentle twist on a little bike on a sunny day

I've also come to learn that this bike makes me very popular wherever I go, particularly with guys between 47 and 52 years old. Their teenage minds believed this very bike could transform their dreams of owning a motorcycle into reality. It was built in a teenager's size and available at a price that invited hopes that their fathers, just maybe, pos sibly, could be convinced to buy them one-a real motorcycle, yet not a crazy fast expensive machine. It's the bike a generation of riders ached for, longed for, and for many of them, the memory of that longing is as emotional as the memory of a first love. Or a first ride.

The CB200 isn't about wheelies, corner-blitzing and blinding speed. It's just a pleasant little bike that slows you down so you can enjoy the reason you started riding in the first place: pure, innocent fun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCottage Industry

December 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupHyde Harrier

December 2010 By Gary Inman -

Roundup

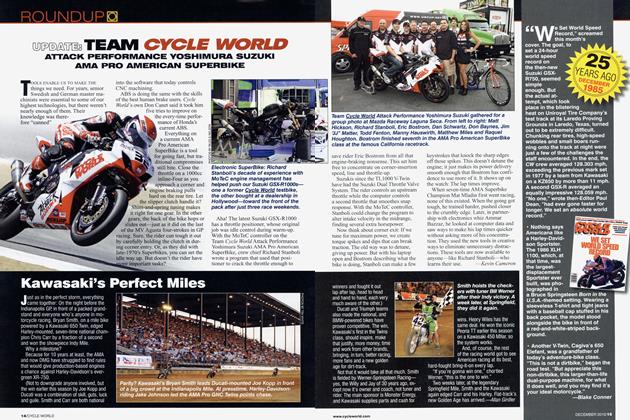

RoundupUpdate: Team Cycle World

December 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

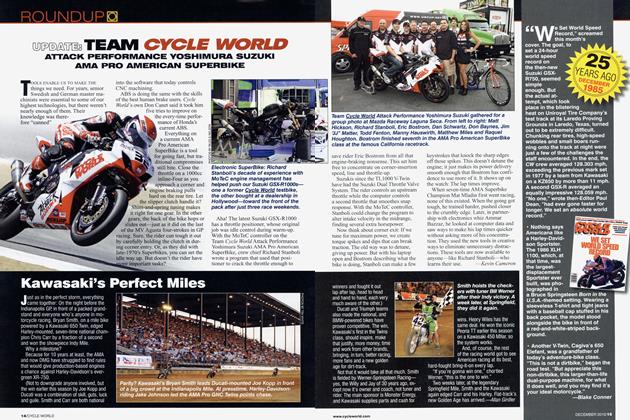

RoundupKawasaki's Perfect Miles

December 2010 By Allan Girdler -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1985

December 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup2011: What's Just Over the Horizon?

December 2010 By Bruno Deprato, Matthew Miles