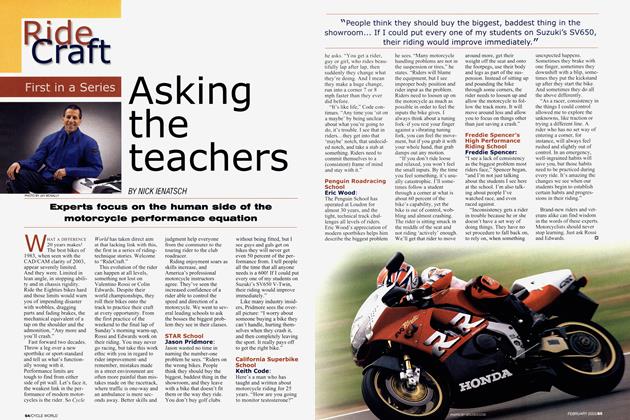

RIDE CRAFT

Learning to ride well with a 500cc World Champion at Barber Motorsports Park

MATTHEW MILES

Be a better rider #9

KEVIN SCHWANTZ MADE 109 STARTS DURING HIS eight-year Grand Prix career, sat on pole 29 times, and won 25 races and the 1993 500cc world championship. He also crashed a lot, often spectacularly, breaking bones in his hands, wrists, arms and feet, and dislocating his left hip. Those rollercoaster results led casual observers to conclude that Schwantz put little-if any-thought into his riding, that his mantra was simply “win it or bin it.”

What is Schwantz’s view? “Early in my Grand Prix career, 15-time world champion Giacomo Agostini was courting me to ride Yamahas,” he began. “We were at Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium. After practice, Ago came up to me and said, T watched you go through this sequence of corners, and every lap you did it a little bit differently. I don’t put that down to inconsistency. This is your first time here; you are learning by slightly varying your lines.’”

Schwantz says he developed this “explore all options” technique as a child. His parents, Jim and Shirley, and uncle, Darryl Hurst, co-owned a motorcycle dealership-Hurst Yamaha & Marine-in Houston, Texas. Schwantz spent hours riding his TY80 trials bike up and down a ditch in front of the store.

SCHWANTZ SCHOOL

“I would try one way to get up the face of that ditch, then another way-a little different angle, varying the pressure on the footpegs,” he said. “I don’t think you can be consistently successful at anything, especially at the top, without putting a lot of thought into it.”

Had Schwantz instead taken a reckless, seat-of-the-pants, throttle-to-the-stop approach to racing, he never would have racked up all those victories. A world title? Forget about it.

Chances are he would not have even survived a single day of his own riding school, let alone earned a diploma.

Now in its ninth year of operation, the Schwantz Schoolformerly known as the Kevin Schwantz Suzuki School-is in its first year at Barber Motorsports Park, located on the outskirts of Birmingham, Alabama, following a successful eight-year run at Road Atlanta. The name change denotes new backing from American Honda and the addition of a fleet of brand-new CBR600RRs to Schwantz’s already impressive stable of late-model Suzuki GSX-R600s; other brands and models may follow in the coming months. Furthermore, the school is now endorsed by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, a first for a racetrack-based program and part of Schwantz’s ever-expanding effort to reach motorcyclists of all ages, backgrounds and riding experiences.

This past May, I joined 37 other students-a school record-at BMP to learn from Schwantz. At morning registration, many of those riders were a bit on edge, their nervous laughter a dead giveaway. Some were concerned about turning a wheel on a racetrack for the first time. Others were unfamiliar with the school’s motorcycles. All had their eyes trained on the dark skies, looking for a break from the rain that was pelting the circuit.

Weather in and around Birmingham had been horrible for much of the weekend leading up to the two-day school.

Severe thunderstorms threatened to cancel Barber’s annual AMA roadrace national, the Honda Superbike Classic. Tornados were sighted nearby. Rain fell throughout the night on Sunday, stretching into Monday.

Even Schwantz was frustrated. “I laid in bed all night thinking, ‘How much longer can it rain?”’

The Schwantz School runs rain or shine. More to the point, and lending understanding to why so many students’ stomachs were tied in knots, crashing is not accepted practice. Tip over, even at walking speeds, and you’ll likely spend the rest of the day watching from the sidelines. So the anxiety was understandable; nobody wants to throw away $1800 (plus a $1000 damage deposit) with a simple slip-up.

Schwantz and his instructors immediately recognized this group neurosis (they’ve seen it before) and attempted to alleviate students’ concerns by pointing out that the wet conditions were actually ideal-yes, ideal-for learning an unfamiliar track, even on strange, untried motorcycles.

Wet or dry, Road Atlanta, with its long, top-gear back straightaway, could be intimidating, especially to novice riders. Barber’s shorter straights invoke less fear in older non-racers, the deep-pocket bike nuts to whom-let’s be honest-Schwantz caters. Plus, everything about Barber is top-drawer. Beautifully manicured grounds are dotted with weird and wonderful metal sculptures. The fivestory museum is spectacular, maybe the finest homage to motorcycling in existence. The track also has nice amenities, including a spacious classroom and an air-conditioned lunchroom.

All of which makes for a comfortable environment that is conducive to teaching-and more importantly, learning.

When Schwantz was initially approached about putting together a track-based riding school, he expressed only mild interest. “Suzuki wanted me to do it, and Road Atlanta was behind it,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘Sure, I’ll try it.’” Now, having delivered congratulatory handshakes to more than 3000 school graduates, he has a different view of the program that bears his name.

“In the beginning, we weren’t so critical of ourselves,” Schwantz said. “Now, we pay more attention to smaller things, from the classroom presentation to the ontrack instruction to our own professionalism.” That helps explain why instructors are forbidden to perform standup wheelies, rolling burnouts and other two-wheel frivolity-unless the name on the back of your Dainese leathers is “Schwantz,” that is...

School curriculum focuses on the following: visual awareness and concentration; body position and steering; cornering lines and reference points; gear selection and shifting; braking, staying smooth and controlling panic.

“The teaching side is pretty basic,” Schwantz said. “The tough part is getting the average grownup, who has been doing things his own way for a number of years, to realize what we are trying to teach him and then make it stick in his head so he can apply it later.”

It all starts, quite literally, in the classroom, probably the last place you want to be when togged up in leathers and other hot, snug-fitting protective gear. Schwantz’s crew of instructors is a likeable, easygoing and highly experienced bunch, many with multiple club and/or national roadracing titles to their credit. Ted Cobb, handling classroom duties at this particular school in Michael Martin’s absence, accumulated 80,000 miles around Road Atlanta. Experience, indeed!

Once he had the floor, Cobb didn’t waste time with small talk. Don’t worry about speed, he said. Rather, focus on finding reference points, looking up the track, and smoothly applying the throttle and the brakes. The speed will come later-naturally.

“We need you to anticipate,” he stressed “not react.”

“Get comfortable on the track, find the inside and outside boundaries,” chimed in Schwantz. “Establish a nice, smooth, relaxed pace. Pick up your reference points.

Find a rhythm.”

Classroom sessions roughly equaled time on the racetrack-20 minutes in the classroom, 20 minutes on the track. Throughout the morning, instructors continued to talk about establishing reference points-cones, pavement patches, distant trees. They are the keys, Cobb noted, to becoming comfortable on a track like Barber with its many blind corners and dramatic changes in elevation.

“Think of the track as a rope,” offered Harry Vanderlinden. “The rope has a series of knots along its length. Those knots are your reference points. Just pull the rope toward you, one knot at a time.”

Some students still found themselves getting into corners too fast.

I watched one student drift wide in a couple of the tighter turns. “Back home in Tennessee,” he later related, “I’m ‘The Guy.’ Nobody is quicker on the street. This is really a humbling experience.”

I’ve heard Schwantz say time and again that he learns something new every time he swings a leg over a motorcycle. Furthermore, he believes in leaving no stone unturned when trying to make a bike do what he wants it to do. Weighting the footpegs to help the bike change directions is an example.

“When you get the bike really leaned over, you don’t want to make any big inputs through the handlebars,” he said. “Those pegs are just like big levers. When you start to slide across the seat, weight the outside peg and use the bike’s mass to steer the motorcycle.”

Schwantz also urges students to get the throttle cracked open as soon as possible after releasing the brakes when entering a corner. That doesn’t mean he wants you to grab a ham-fisted handful mid-corner. It’s a subtle, barely detectable movement intended to transfer load from the narrow front tire toward the rear of the bike. I found this techniqueSchwantz refers to it as “neutral” throttle-especially useful in Charlotte’s Web, a downhill, off-camber, double-apex turn.

Most of Schwantz’s students are street riders-appropriate since this is a school for improving riding skills, not racing skills. The students are used to sitting in the middle of the seat, even on hard-edged racer-replicas like CBRs and GSX-Rs. Hanging off while negotiating a town-center intersection is silly, but on the racetrack, where cornering speeds are higher, it’s all-important. Problem is, many students, me included, were waiting too late before shifting their weight toward the inside of the corner, upsetting the bike at a time when stability is critical.

“I’d like to see you set up earlier for corners,” suggested Vanderlinden. “Use what Kevin calls a ‘lazy’ riding style.”

Schwantz later explained that when he was racing, every time he slid back to the center of his twostroke 500cc Suzuki, the bike wanted to set itself into a big, violent wobble. Riding that type of motorcycle, with its narrow powerband and light weight, forced him to get into position early for corners. “If I didn’t have to get back in the middle of the seat for a big, long straightaway,” he said, “I’d just leave one butt cheek set off the side of the seat.”

There is a lot to take in during a two-day Schwantz School. But all the effort on the part of Schwantz and his instructors is wasted if students don’t absorb and benefit from the information passed along to them. I asked several instructors what traits they look for in a student. Number one was the ability to listen. Vanderlinden cited school regular John Hensley, an actor best known for his role on TV’s “Nip/ Tuck,” as a good example. “He’s used to taking direction,” said Vanderlinden. “With some guys, it’s in one ear and out the other.”

So pay attention. And, as Schwantz says, explore all options.

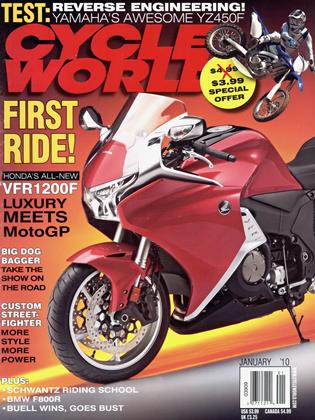

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFrom One Enthusiast To Another

JANUARY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Best Bargain:

Best Bargain:Honda Interceptor

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

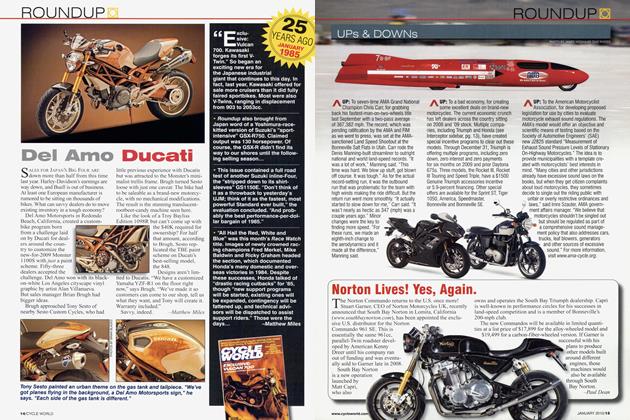

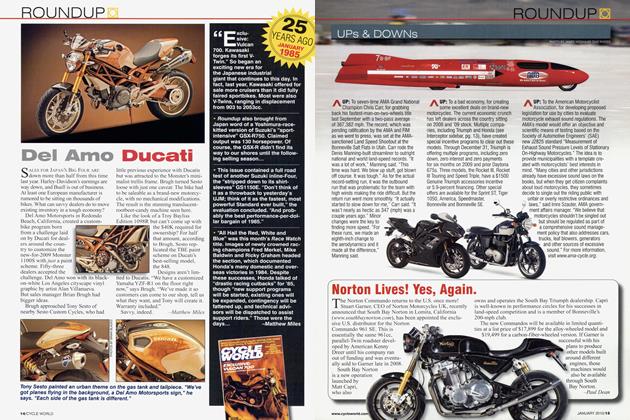

Roundup

RoundupDel Amo Ducati

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

25 Years Ago

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

JANUARY 2010 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton Lives! Yes, Again.

JANUARY 2010 By Paul Dean