MAKING THE MOVE TO Moto GP

RACE WATCH

A winning résumé is only half of the battle

MATTHEW MILES

WHO WILL BE MOTOGP’S NEXT STAR? BEN SPIES IS ONE POSsibility. He has made clear his desire to move from domestic AMA racing, where he is an established two-time Superbike champion, to the politically charged international world of GP racing. He would like to do this as soon as possible. This season, in addition to his AMA duties with Yoshimura Suzuki, the 23-year-old Texan will race a Suzuki GSV-R800 at MotoGP’s two U.S. rounds-Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca in July and Indianapolis Motor Speedway in September. Two more wildcard rides in Spain are open for discussion.

This is a fine plan that has worked for others in the past. Successful performances both here and abroad would generate interest on the part of teams, sponsors and fans. In Kevin Schwantz, he has a respected mentor with deep ties to the Suzuki factory in Japan. Yet Spies, aware that doors often close as quickly as they open, admits he would consider other offers if the result were a competitive seat.

This is the same predicament Nicky Hayden faced five years ago. He, too, came through the AMA ranks, on dirt as well as pavement. In 2002, in only his second AMA Superbike season, he won the Daytona 200 and that year’s series title. An exceptionally well-rounded rider, he lacks only a win at a mile dirt-track to join Dick Mann, Kenny Roberts, Bubba Shobert and Doug Chandler in the “Grand Slam” club.

Yamaha was interested, and higher-ups at American Honda, along with Mick Doohan, the Australian five-time 500cc world champion, then still a Honda employee, lobbied hard for a spot for Hayden on the factory Repsol squad alongside Valentino Rossi. The Kentucky native eventually signed with Honda and finished fifth overall in the world championship in 2003.

In making the transition to Europe, Hayden was forced to adapt to a world turned upside-down. "Nicky's an Amen can, so it's completely different, the cul ture shock," said Doohan, who underwent a similar upheaval when he came into GP racing in 1989. "It definitely takes a couple seasons under your belt to feel comfort able and understand the environment."

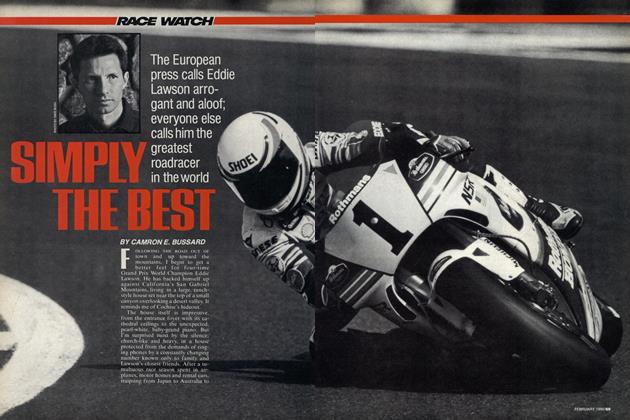

This is no small issue, and unlike fel low rear-steering dirt-trackers-turned pavement-stars Freddie Spencer, Eddie

Lawson and Wayne Rainey, among oth ers, Hayden didn't have an Erv Kanemo to or a Kenny Roberts to show him the way. The racetracks were unfamiliar, and he couldn't understand the languages spo ken around him. Ordering a meal in a res taurant was difficult. He was contracted to a Japanese factory, teamed with an Italian icon and backed by a Spanish oil company, Repsol. All of which had their potential hurdles.

“America is a large market, so hiring an American rider has never been a problem for the Japanese,” explained Doohan. “The Spanish sponsor obviously would like a Spanish racer or to be winning races-either one. I wasn’t Spanish when I had that sponsor, but we had a Spaniard in the race team, Alex Criville, who eventually won the championship.”

When Doohan made these comments to me in 2004, Rossi had just left Honda for Yamaha. Four-time 250cc World Champion Max Biaggi had joined Honda, but by season’s end, he’d won just two races; Rossi won nine in ’03. Hayden had yet to score his first victory. “Over the past two seasons with Valentino, Repsol was getting exposure from winning races and that was enough,” said Doohan. “We’re not having the results that we’d like, and we don’t have a Spaniard.”

Repsol got another Spaniard two years later, when Dani Pedrosa joined the team. The arrival of the former 125 and 250cc world champion signaled a turning point for MotoGP. Pedrosa and fellow class rookie Casey Stoner were the prototypes for a new breed of GP rider: small, impossibly light and, unlike Hayden (or most of his American GP predecessors, for that matter), possessing no Superbike experience. Standing nearby them, the gangly Rossi looks like Michael Jordan. Muscled-up 5-foot-11,160-pound Spies could be mistaken for an NFL cornerback.

Despite their diminutive dimensions, or possibly because of it, Pedrosa and Stoner have gotten results. Together with similarly sized Marco Melandri and Toni Elias, who entered the series in 2003 and ’05, respectively, they’ve amassed 20 premier-class wins, with the lion’s share (10) going to Stoner, the reigning title-holder. This year, they’ll be joined on the grid by Andrea Dovizioso, Alex De Angelis and Jorge Lorenzo, all veterans of GP racing’s smaller classes. In contrast, Hayden, fellow Americans Colin Edwards and Kurds Roberts, plus Australians Troy Bayliss and Chris Vermeulen and new Yamaha recruit James Toseland, are the only ex-Superbike riders to join MotoGP during the same period. Collectively, they have five GP wins.

Why draft riders from the smaller classes? Two reasons: First, the current 800s, with their wide-reaching electronic controls, are much like 125s. Riders are taught from an early age that throttle opening should reflect lean angle-the more upright the bike, the larger the throttle opening. But 125 s are far lighter than and not nearly as powerful as production-based 600s or 1000s, and their throttles can be opened more abruptly with less concern for available grip. It is now the same in MotoGP. Also, 125 riders rely on high cornering speeds to maintain momentum, another plus with the 800s. This may explain Stoner’s many crashes on a Michelin-backed satellite Honda 990 during his 2006 transition season. Switching last year to the powerhouse Bridgestone-shod Ducati-a masterpiece of electronic interventionhe fell with far less frequency.

Second, they know the tracks. “Casey’s done six or seven years of learning circuits and learning the environment,” said Doohan. “It adds up.” Further, they know how to set up their machines for those tracks. “I know how to fix my bike to make it work on the parking-lot tracks we run on,” said Spies. “It’s not the same when you go to a fast, flowing track in Europe. A problem that you have on a 250 on those tracks is going to be the same on a big bike. They’ve got a big head start on us.”

American Jason DiSalvo was once on the same track as Pedrosa and Stoner. In 1999, at age 15, he contested four 125 GPs-two in Europe and two in South America. The following year, he raced the entire series. At 17, he moved up to the 250 class, finishing 10th overall. “I raced with Casey Stoner,” he said. “I raced with Dani Pedrosa in Spain. Chaz Davies was over there at the time, too.” Out-ofpocket costs eventually drove DiSalvo back home. For $100K, he could have been “one of the select few,” but for that amount of money, his father decided, DiSalvo could do something in America that was “guaranteed.” Back in the States in 2003, he won one AMA 750cc Superstock race and was the highest-placing Superbike privateer. In ’04, he accepted a Yamaha ride in AMA Supersport and Superstock. He currently races a factory YZF-R1 in Superbike.

Steve Bonsey is another American who opted for the GP route. Following in the footsteps of Rainey and John Kocinski, the 17-year-old Californian is Kenny Roberts’ latest project. He made his debut this past year in the 125 class on a KTM. A dirt-tracker with little previous pavement experience, Bonsey ended his season in 25th overall, with a best finish of 13th at Jerez, Spain. “He can ride,” said Roberts. “Whether he can impress his bosses...”

What struck me about Bonsey when I met him last year at the Italian GP is that he’s just a kid, and very much alone. I asked him about school. “I took the GED,” he said, “but that didn’t work out so well.” His little finger, badly disfigured from a crash earlier in the season, revealed the serious nature of his chosen occupation.

Later, I asked Doohan for his opinion of Bonsey. “I just met him yesterday,” he admitted. “I looked up and he was running off in the grass. Throwing him in the deep end isn’t probably the safest way, but obviously Kenny believes in him. That’s what I mean: It’s a whole different learning environment for Americans than, say, a European. If things don’t go well on Sunday afternoon, they can just go home. It’s not that easy for Bonsey.”

“That’s a tough situation for a kid,” agreed Hayden. “How could he say no, though? He might not ever get that opportunity again. Sometimes you only get one shot at it, and you’ve got to run with it. He’s in deep. It’s tough over here, especially in that class, and he’s got a lot to learn. I’m sure there are a few habits that are hard to break, and he’s probably going a lot faster in left-handers than rights. I’m still the same way.”

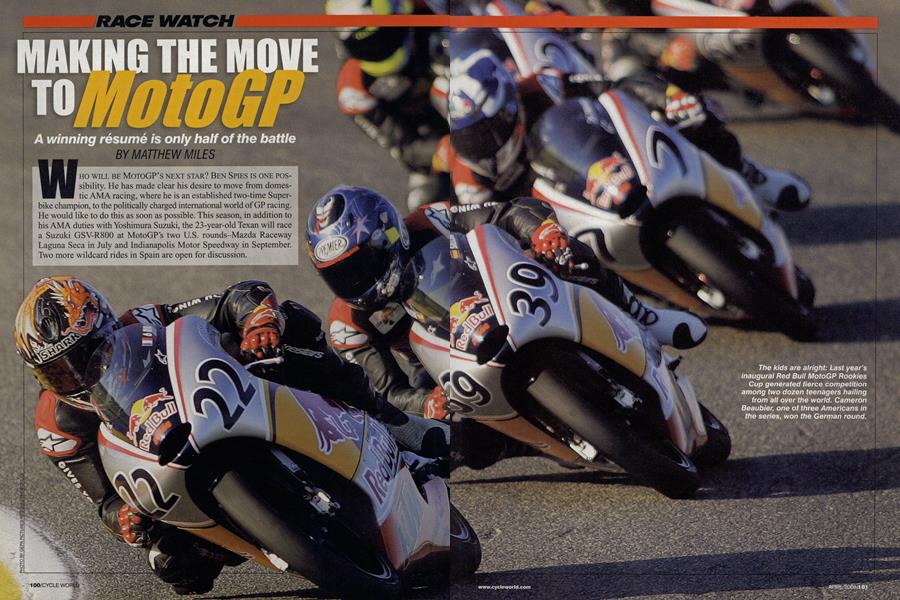

Italy also provided a firsthand opportunity to learn about the Red Bull MotoGP Rookies Cup. This well-funded spec series is open to 13-16-year-oldsmale and female-from around the world. Tryouts were held, 23 riders chosen, all to ride identically prepped KTM 125s at eight European venues. Three Americans-Californian Cameron Beaubier, Washingtonian J.D. Beach and Tennessean Kris Turner-made the cut for last year’s inaugural program. The concept is simple: Find, in a relatively safe environment, a replacement for Rossi, MotoGP’s shining star. As such, Rookies Cup is not just about speed, damn the personalities. That helps to explain why Beach, a dirt-tracking pavement novice like Bonsey, was chosen. Style points count.

Hayden, for one, likes what he’s seen of the Cup. “At Jerez, the first race, me and my brother Tommy watched every lap when Beaubier was up front battling for it,” he said. “I’ve been impressed with all of them. They all seem like really cool kids. The 800s are not nearly as physical as the 990s, so the way MotoGP is headed right now, 125 is the place to be.”

This year, in an effort to foster young talent stateside, the Red Bull AMA U.S. Rookies Cup will run the same Euro-spec KTMs during select AMA Superbike weekends. Schwantz will coach the nearly two dozen teens culled from 600 applicants and 104 invitees who tried out this

past fall at Barber Motorsports Park in Alabama. If there’s a catch, it’s the fiveyear commitment participants must make to Red Bull. Further, the Austrian energy drink company has a hand in determining where the kids will end up after each of those years. That’s a big corporate obligation for riders barely into their teenage years. “They may not know if they have the commitment and the desire to live out of a suitcase, to travel around the world, not be able to see all the kids that they’ve gone to school or grown up with,” Schwantz acknowledged. “It’s a different lifestyle. For most people who go to GP racing, that’s the biggest shock: a suitcase and a hotel room. It’s tough on you.”

Spies, however, is an adult. He long ago made his own commitment to a career in racing, and he has worked in a determined fashion to achieve his goals. Yoshimura teammate Mat Mladin has been an excellent sparring partner, pushing Spies to a level that he would not have reached on his own. “Last year, after I crashed at Road Atlanta, then came back and finished second to him, I rode up and shook his hand,” said Spies. “He looked at me said, ‘We’re not good for each other’s health!”’

Following last season’s MotoGP finale at Valencia, Spain, Spies tested the Suzuki, lapping within 1 second of competitive times. “It was a lot like riding my old 250,” he said. “I do so many things, especially in the middle of the corner, on my Superbike that my team says, ‘Don’t do that! ’ When I jumped on the GP bike, it was like I was home.”

For now, he must once again contend with Mladin. “We won however many races last year and never finished worse than second, yet we barely managed to win the title,” he said. “For me to win the title again this year, I’ve got to win races and I can’t make mistakes. Racing Mat is tough. It’s going to be half-tenths of a second per lap; that is what’s going to separate first from second. I can’t be thinking about racing a GP bike when I’m lining up against him.”

To make the move to MotoGP, he will need a team and sponsor that believe in his abilities, that will give him the time he will need to learn the European culture, the tracks, the languages.

“MotoGP bikes are different than Superbikes,” admitted Hayden, “but at the end of the day, a rider of Ben’s caliberanybody with talent and determinationcan adapt. It’s not like starting completely over. It’s still a motorcycle, and the guys who are fast know that.”

MotoGP is a business that sells a lot of things, and for a rider to succeed in that series, he needs more than speed. But being fast doesn’t hurt.