RIDING ’ROUND THE ’RING:

RIDE CARFT

Two days with BMW Rider Training at the Nürburgring

MATTHEW MILES

RACING HISTORIANS COUNT THE 24 HOURS OF LE Mans, Formula One’s Monaco Grand Prix and the Indianapolis 500 as the three most significant events in motorsport. Notably absent from that list

is the Nürburgring, thought by many to be the toughest-and most unforgiving-racetrack in the world.

First of its kind in Germany, “The Green Hell,” as F1 great Jackie Stewart infamously labeled it, was built between 1925-27 around the village and medieval castle of Nürburg in the Eifel Mountains. Originally, the full course totaled a daunting 17.6 miles; in all, there were 172 corners84 right-handers and 88 lefts-with nearly every imaginable combination of camber, gradient and radius.

The first race, won appropriately by young German Rudolf Caracciola, was held on June 19, 1927. Two years later, the track was shortened to include only the 14.2-mile Nordschleife (Northern Loop). In 1936, one year before his death in a top-speed record attempt, motorcyclist-turnedcar-racer Bernd Rosemeyer became the first person to lap the circuit in less than 10 minutes.

Seven decades later, as a guest of BMW at its annual Nürburgring Nordschleife Race Track Training, I found myself winding around the same incredible, heavily forested circuit at a pace identical to that of the legendary three-time ’Ring winner. Thanks to huge advances in technology, significant improvents to the course (now 12.9 miles in length) and excellent instruction on the part of the enthusiastic and well-trained staff, my on-track experience was a joy. I can only imagine the heart-pounding stresses that Rosemeyer must have endured while wide-open at the wheel of his 16cylinder Auto Union Silver Arrow. Or maybe not. Describing Rosemeyer, Caracciola said, “Bernd literally did not know fear, and sometimes that is not good.”

No manufacturer devotes more effort and expense to rider training on dirt, road and track than BMW. European training venues include the Compact Training Course at the Munich Airport, racetracks (Nordschleife and Salzburgring) and several enduro parks. According to the official program guide, levels of difficulty range from “one helmet” (beginners with limited experience) to “two helmets” (advanced motorcyclists with extended experience) to “three helmets” (skilled riders who wish to master every type of terrain).

Last September, 20 years after the program debuted in Europe, BMW North America began rider training at its South Carolina performance center.

In the case of the two-helmet Nordschleife training, 950 euros (about $1300) buys two days of on-track instruction, food and two nights lodging at the modern, memorabiliafilled track hotel. Participants supply or rent their own motorcycles and riding gear. (BMW outfitted American moto-journalists with brand-new Kand R-bikes.)

Our class consisted of 70 riders broken into nine groups, each with at least one instructor. Former GP racer Jürgen Fuchs, on hand as a guest teacher, received a hero’s welcome.

Each day would begin rain or shine with two slow-speed sighting laps, followed by section training, a catered lunch and, rounding out the afternoon, complete laps of the course, usually two or three at a stretch. Overtaking instructors or other students was verboten. When asked what constituted a respectable lap time, headmaster Klaus Hammer replied, “Everything below 10 minutes is fast. After that, it’s up to you.”

On Day 1, we gathered at 8:30 a.m. on the front straight, which is as long as some entire tracks. Most school-goers were male, old enough to know they were never going to win a world title and in large part dressed in textile riding gear; unlike at U.S. track days, full leathers and knee pucks were in the minority. Our affable instructor, Peter Sperlich, sporting two-piece leathers and virgin pucks, has worked for BMW since 1990, previously in sales and marketing, and is currently in dealer development. “Rider training is not work,” he said, flashing a toothy smile.

Our initial sighting laps hammered home everything I’d read and been told about the ’Ring: With Armco lining both sides of the circuit, even a slight error in judgment could be lethal. Gravel traps, a staple at most circuits, are few and far between. It’s no wonder F-l hasn’t visited the ’Ring since 1976. Grand Prix motorcycles stuck around for two more years, long enough for Kenny Roberts to wrap up his first world title with a third-place showing.

Sperlich separated the track into a dozen sections; in two days, we would cover just five. Unlike CW Road Test Editor Don Canet, who prepped for his visit to the Nordschleife last summer (see “Ring Fling,” CIV, November, 2007) by playing video games that featured the ’Ring, I took the analog approach, going into the experience blind and looking to Sperlich and his colleagues for insight. He spent an hour on each section, leading our group of six back and forth like a doting mother, periodically stopping to explain the intricacies of each comer and methods we could use to link them together. For me, a non-German speaker, just remembering the names of the scctions-Tiergarten,

Hohenrain, Schikane, Hatzenbach,

Hocheichen, QuiddelbacherHohe, Flugplatz, Schwedenkreuz,

Aremburg and Fuchsrohre-was a mammoth task.

My feeble memory aside, section training was fun. Complete

laps, however, were an altogether different story, like stepping up from The Black Stallion to War and Peace, especially when Sperlich began to quicken the pace. What’s next, a blind fifth-gear left followed by a decreasing-radius thirdgear right? Or does that come later? Hey, isn’t that where Nikki Lauda nearly burned to death? You get the picture:

I was lost. A fellow student told me over dinner that while he had a visual grasp of the circuit, drawing a map of the course from memory would be impossible. Fuchs admitted he needed three years to learn the track. “Don’t worry,” Sperlich assured me. “You’ll make a 100 percent improvement tomorrow.”

I didn’t sleep well that night, but I wasn’t alone in that regard. Another journalist dreamed he’d crashed spectacularly. “I tucked the front,” he explained at breakfast the following morning, “and woke up with my heart pounding!” I’d had no

such dreams; in fact, my bike, an R1200S rolling on Michelin Pilot Power radiais, had served me well. Good power, nice sounds and excellent compliance from

the fully adjustable Öhlins shocks

fitted to the Telelever front and Paralever rear suspensions. A couple clicks of rebound damping was the only change I made to the setup. I even used the heated handgrips on the short early morning commute from the hotel to the track. I drew the line with the expandable saddlebags, leaving them in my room.

Sperlich was right, although “100 percent” might be stretching it a bit. Bottom line, when the second day rolled around, I felt

more comfortable on the course, especially in the afternoon when I stepped down from the footpeg-scratching, ex-racer “A” group to the thinning-hair, slightly overweight, wick-it-up-on-the-exits “B” group. Perfect pace for me, should I have the good fortune to make a return trip, would be something between the two-call it “A minus.” Late in the afternoon, we strapped on our helmets for a final three-lap run. Before I left for Germany, Canet had advised me, “Don’t start another lap if you’re low on fuel.” Sure enough, after the second lap, an easy 11 on my 1 -to-10 funmeter, the low-fuel warning began to flash. Common sense prevailed but, man, I really wanted to make one more circuit.

That evening, after a light meal and much back-patting, we headed into the German countryside bound for the Frankfurt airport. As we jetted away from the track, I thought, forget Le Mans, Monaco and even Indy, nothing-absolutely nothzzzg-compares to the Nürburgring. K2

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontElectric Chair

February 2008 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Road To Harleysville

February 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCControlled Motions

February 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2008 -

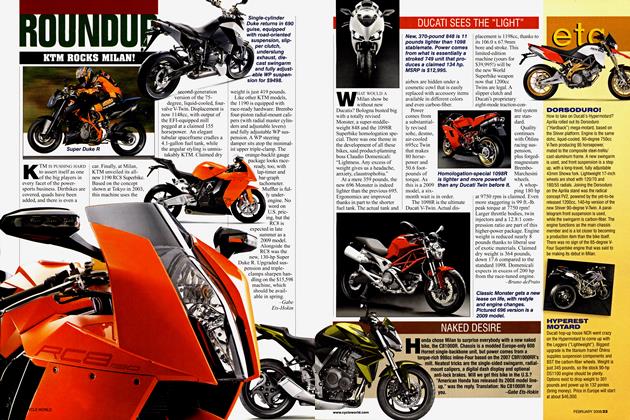

Roundup

RoundupKtm Rocks Milan!

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin -

Roundup

RoundupNaked Desire

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin