CONTROLLED OUTCOME

RACE WATCH

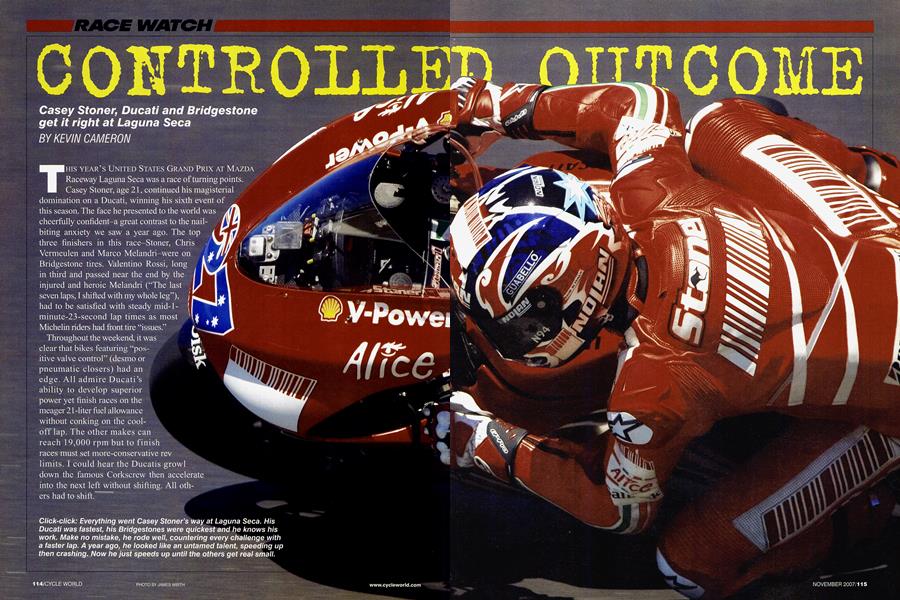

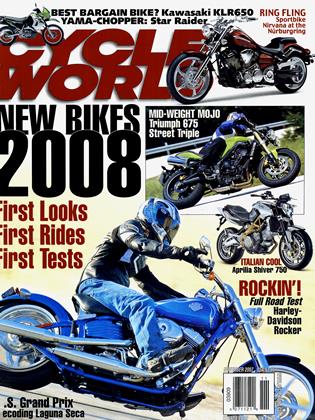

Casey Stoner, Ducati and Bridgestone get it right at Laguna Seca

KEVIN CAMERON

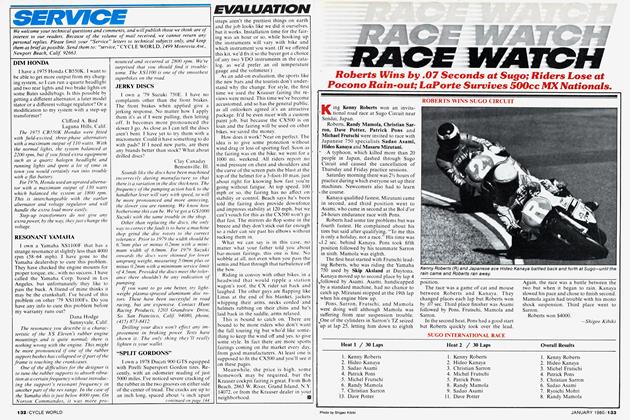

THIS YEAR’S UNITED STATES GRAND PRIX AT MAZDA Raceway Laguna Seca was a race of turning points. Casey Stoner, age 21, continued his magisterial domination on a Ducati, winning his sixth event of this season. The face he presented to the world was cheerfully confident-a great contrast to the nailbiting anxiety we saw a year ago. The top three finishers in this race-Stoner, Chris Vermeulen and Marco Melandri-were on Bridgestone tires. Valentino Rossi, long in third and passed near the end by the injured and heroic Melandri (“The last seven laps, I shifted with my whole leg”), had to be satisfied with steady mid-1-minute-23-second lap times as most Michelin riders had front tire “issues.”

Throughout the weekend, it was Ä clear that bikes featuring “posm itive valve control” (desmo or pneumatic closers) had an ~ edge. All admire Ducati’s ability to develop superior power yet finish races on the meager 21 -liter fuel allowance without conking on the cooloff lap. The other makes can reach 19,000 rpm but to finish races must set more-conservative rev limits. I could hear the Ducatis growl down the famous Corkscrew then accelerate into the next left without shifting. All others had to shift.

Stoner controlled the race, keeping a second between himself and Vermeulen’s Suzuki through the first 10 laps, repeatedly improving upon his 1 -minute-22-second pace as required. In time, Vermeulen’s tires faded, slowing him slightly. Stoner then increased his lead to 10 seconds, slowing toward the end to conserve fuel and not even using full throttle on the front straight, where his top speed dropped nearly 6 mph.

Melandri, on a lease-team Gresini Honda, had been fast in practice but had bailed in a terrifying rag-doll tumble. With an injection for his damaged ankle, he continued to ride, qualifying only 10th after having been second behind Stoner in the first and second free practices. After the race, he said he was stiff in the early laps but then ‘T found a rhythm and I think maybe I can make a good race.” He did just that, climbing from an early sixth to pass Rossi for third on the 15th of 32 laps.

Melandri’s gritty ride (he had to be carried into the pressroom) did not obscure the glaring fact that a leased Honda (even slower than the factory Hondas have been this season) on Bridgestones was faster than Rossi on Michelins. When the Bridgestones are right, they look like they could do another whole race. Tires are not just “supplies” like drive chains or cooling water. They are racedetermining factors, quietly responsible for most of the performance gains we see.

Michelin has provided much of this gain with steady innovation. This season, the French company has faltered. A year ago, CEO Edouard Michelin died in a boating accident, and long-serving Competition Director Pierre du Pasquier retired.

Bridgestone technology appears as a rounded hilltop. Push the tires off their peak and they lose little height. Michelins, by contrast, seem currently balanced atop a flagpole-one misstep and they fall. Yet the previous weekend at Sachsenring in Germany, the shoe was on the other foot. The left sides of Bridgestones gave up, letting Dani Pedrosa through to win on his Michelin-shod factory Repsol Honda.

Honda stated last year its belief that metal valve springs could continue to do the job, while Suzuki and Kawasaki developed pneumatic spring systems and Ducati remained faithfiil to desmo (which employs a second cam lobe and an Lshaped closing lever to shut its valves). To the surprise of many, Honda’s 800cc V-Four, still with metal springs, became the “sick man of Europe” this year. The problem is that at extreme rpm, only part of the energy supplied by the cam compresses the spring and accelerates the valve upward off its seat. The rest of that energy persists as wave motion, stored in the oscillating coils of the spring. Making the spring stiffer only adds more mass, storing more energy as fatiguegenerating, end-to-end wave action in the spring.

Every stress cycle in metal causes tiny rearrangements in the atomic bonds that hold it together. Thus the metal becomes like the film badge worn by nuclear workers, recording its stress exposure. Metal springs have become very sophisticated, extending their performance, but as stress exposure grows, so do defects in the metal, originating at inclusions main-

ly of silicon dioxide (yep, that’s sand). Techniques like vacuum remelting and cold-working reduce inclusion size and give them less harmful shapes. Japan’s Kobe Steel Company is a respected source of valve spring technology. Titanium springs, which are difficult to make, add

another dimension.

The problem of valve operation is like riding a motocrosser over a whoop. In this case, gravity takes the place of the spring. If the whoop is short and steep, the bike wheelies easily over the top or flies off the top (valve float). Valve float breaks valves, which cannot survive hard impact with their seats. To prevent jumping at higher speed, we make the “hill” (cam lobe) gentler-wider and lower. Cutting valve lift in this way reduces engine performance, and longer timing (a “wider hill”) invites a peakier powerband.

Metal springs tie the designer’s hands. Higher rpm is necessary for more power but to reach it, valve lift has to be reduced and duration increased. Would you rather be hanged or shot? The compromise has been to work the springs very hard, requiring daily replacement. Then it’s not a surprising statistic if a spring breaks a few minutes early, as may have been the case with Nicky Hayden’s smoky Sachsenring blow-up.

Jeremy Burgess, Rossi’s crew chief, noted that, “They didn’t find the gudgeon pin, and heads of the valves were coming out the exhaust pipe.” He further observed that “you want an ideal valve lift, say, of around 12mm on the inlet, but you’re probably down to 9 now because things are beginning to rattle a bit too much.”

This valve lift problem has left metalspring users short in the horsepower department. “We need to take the next step,” Burgess said. Honda and Yamaha are> believed to be furiously developing pneumatic systems.

The new tire rule has done more than cut Michelin off from using its automated C3M manufacturing system to make Sunday’s tires Saturday night, based upon feedback from all the practices. Riders must now place their tire bet on Thursday and receive their allocation of 14 fronts and 17 rears, including two qualifiers. By Sunday morning warm-up, all the riders have chosen their tire fit, and what’s left is either too soft or too hard. On Sunday morning, some riders must use “hard rejects” and appear uncompetitive, while others have too-soft tires left, making their times demoralizinglyand artificially-quick. Stoner was in the second category, setting a stunning new Laguna record of 1:21.975 in the warmup. Riders take this in stride, but it’s confusing for fans.

Last year, Laguna was full of bumpsone just off the bottom of the Corkscrew threw several riders out of the saddle. The pavement has been renewed and adjusted, but many riders found the old bumps still present. The Big One at the Corkscrew, happily, was much improved. Pedrosa, who would finish fifth, said, “Laguna is the only circuit that flows with the hills-not designed on a computer.” The new pavement is a major part of our story and of Michelin’s uncompetitiveness at this event. Higher grip allowed the lap record to fall and it worked tires harder. Bridgestone sent technicians to take casts of the new pavement’s texture, as Michelin has done in the past. The size, scale and sharpness of asperities in the pavement provide clues to how rubber compounds will perform as they slide over it.

On Friday afternoon, Burgess said, “The racetrack’s very green here. We’re getting some tire wear on the front that we would expect on a green racetrack. We go harder to stop the tire tearing up and we see that into the Corkscrew we’re braking 14 meters earlier and we’re losing time. The hard tire is not doing its job, and it doesn’t look any better than the soft tire. We can eliminate the hard tire for our race. We can work with the soft tire now and bring our braking distances back to where they were this morning. And hope that the racetrack will come toward us a little bit with more rubber down, which it seems to do. If we do get into a bind, we’ve got the hard one, but we know that with it we’re going to struggle in the braking.”

How marvelous to be able to actually measure what a change in rubber compound is doing on the track! More difficult to know is the effect of the abrasiveness of the new track surface on tire condition-and how fast the field will lay down rubber that can “bury” many of the sharp edges that constitute that abrasiveness. The closer you look at the details, the less you know. Yet the tire choice must be made. The Michelin “tire choice chart” for this race indicates that all seven of its riders chose “medium” front and rear slicks.

All tire variables are interrelated, so there is no changing of one without affecting all. And performance may be good at the expected temperature but useless at 5 degrees hotter or cooler. Mesdames et messieurs, place your bets.

Tire companies are tight with information. As longtime Michelin man Colin Edwards put it, “We don’t get any information.” Tire-makers’ press releases disclose gems like, “Brand X riders eager for victory at Laguna!” At the end of 2005, Honda was out of grip, while Yamaha’s firing order gave them plenty. Michelin got busy and produced a range of soft-carcass, ultra-low-pressure tires that laid down a larger footprint.

When inflation pressure is reduced, tire casing entering or leaving the footprint must bend through a sharper angle. This increased flexure generates more heat that could make a soft rubber “give up,” losing its peak properties-as a qualifier does in a lap or two. To prevent this, the casing is made thinner, reducing the amount of rubber that is flexing and the heat generated. This process was ongoing at Michelin through the 1990s, as tire pressures in the 500cc class came down to 28 psi and finally to 24 (or 22 for at least one team!). Each reduction brought with it a roughly inversely proportional increase in footprint area. Meanwhile, softer compounds-some of them formerly used only in wet conditionsbegan to appear on dry tires.

In response to Honda’s demand for more grip, pressures were reduced yet again. Concerns about possible rim damage were offset by the continuing trend toward smaller rim sizes (all Michelin fronts at Laguna were 16 inches; rears were 16.5 inches). A tire’s fabric carcass, however, gets its rigidity from tension created by inflation pressure. When I asked Edwards about his role as team tire tester, he said he’s no use to Rossi now because their tire preferences are so different.

Speaking of this, Rossi said, “We ride in a completely different way, me and Colin. I have a good speed in the center of the corner, and my speed is less up and down-more constant. Colin is more stop and restart. So Colin needs more traction. I need more stability.”

Edwards has enjoyed top qualifying positions this year. I asked, “When it’s right, what is it that’s right?”

“When it turns when / want to, and it has traction,” he replied. Edwards went on to say that he likes the new soft constructions-they “solve” the back end of the bike, allowing him to concentrate on the front.

By contrast, Rossi said, “I need more stability because for me with the soft construction, when I go through the corner and I touch the throttle, always the rear moves.”

I suspect what he is feeling is some buckling of the very soft carcass under his high cornering load. But when Edwards says “traction,” he means not sidegrip but the grip needed to accelerate. Edwards finished 11th, his times decaying from 1:23s to steady :24s, and finally, at the end, :25s.

And the other Americans? Fans’ yearnings for World Champion Nicky Hayden and John Hopkins to do well were dashed in their first-lap Turn 2 collision. Roger Lee Hayden impressed in a one-off ride to 10th on a Kawasaki after qualifying 15th. Canadian Miguel Duhamel, filling in for absent regular Toni Elias on a Gresini Honda, qualified 19th and was out after 10 laps.

These are electronic motorcycles and not everyone likes it. I asked Loris Capirossi, who was heroically successful on last year’s Ducati 990 (and second at Sachsenring the previous week), what is different now. He replied that the engine control program used in early testing suited his aggressive throttle style. But when the “fuel economy program” needed for actual racing was substituted, conflict emerged. The new 800s must be ridden very precisely in an energyconserving, high-comer-speed 125cc style. Deviations from this are punished by slower lap times. Capirossi said he’d even welcome the 500cc two-strokes back. “That is a strong engine,” he said. “In one lap, half of this field would fall off.”

Hayden said, “Every year, the meetings get longer, the testing gets longer. We used to just work on suspension, tires, gearing, but now we have to set the wheelie control for this part of the track, the traction control for that part of the track.”

Some fear the sport is becoming a dry technical exercise and want electronics banned. With the present big, powerful engines, no electronics would mean 1989 all over again harsh power delivery, chancy slip-and-grip corner exits and potentially injurious highsides. Must riders do parts of their jobs from hospital beds? Back to computer-free magnetos and carburetors? 1 hope not.

Years ago, when Jack Brabham began win Formula One races in the rational rearengined Cooper against a field of slewing front-engine Ferraris and Maseratis, critics said much the same. “Racing must not come a contest of colorless technicians.” That is, races should be won by “heart, displayed by playboy drivers, such as Von Trips or De Portago, in cars always half of control. We can do better than this.

How does Ducati combine lcave-you-fordead power with fuel economy? I spoke with Ducati Corse Managing Director Claudio Domenicali. He said, “We employ fuel-conserving techniques in every regime of engine operation, from idle to peak power.”

He also admitted, “Our engine has very bad flat spots.”

Then how can they achieve the smooth torque delivery that tire grip requires? The simplest answer is by automated throttle modulation. Honda dominated early new-era four-stroke events by smoothing engine torque. Any troublesome torque peaks were clipped off by programmed ignition retard. Retard is out now because it wastes fuel. Instead, fastacting throttle actuators rapidly flutter the butterflies as the engine accelerates, delivering the average torque the rider commands from the throttle grip but trimming the engine’s natural peaks and filling the valleys. Supplementary help may come from changes in ignition and fuelinjection timing. With this trimming and filling, Ducati can use valve timings that make big power and yet retain smooth driveability. All this is enhanced by the high valve lifts possible-even at 19,000 rpm-by positive valve drive.

The show goes on, technology expands and problems are solved. Every door this process opens reveals wide vistas of imagination-stimulating ignorance. Forever. Ö

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMy Day of Living Dangerously

November 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThings Change

November 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCNatural Orchestra

November 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2007 -

Roundup

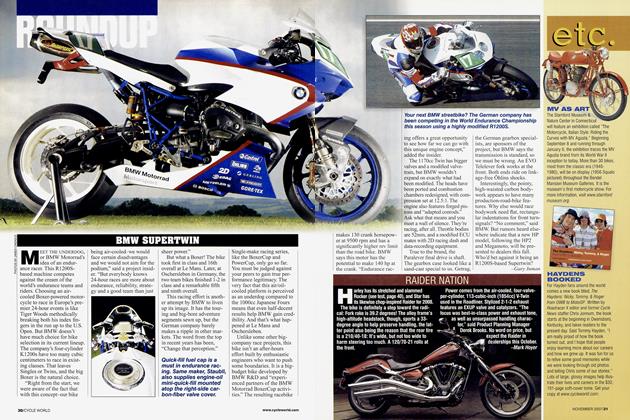

RoundupBmw Supertwin

November 2007 By Gary Inman -

Roundup

RoundupRaider Nation

November 2007 By Mark Hoyer