A MODEST PROPOSAL

The Daily Rider Re-Examined

Do you use your motorcycle as your primary mode of transportation? Or, if you’re not a “daily rider” in the literal sense, does your bike serve as a frequent alternative to four wheels?

It’s been a long while since I’ve considered these questions in earnest. In fact, the last time was 1980 and I was at grad school, squeezing nearly 60 mpg out of a 500cc Triumph Twin and riding past long lines of cars waiting to fill up at the local gas station. High fuel prices and rationing were temporary facts of life in the U.S. and a bike was the hot setup for commuting.

Today, a midsized pickup truck serves as my primary transport while my motorcycles are mainly for sport. I admit when it comes to getting around on weekdays I’m just like most American motorcyclists: I take the steel cage, not the bike.

That’s a shame, and we can all do better. Most of us love motorcycling for the sheer pleasure of riding, but too few of us are exploiting the practicality and, I believe, societal benefits of our machines for regular use.

Bikes take up less space in an increasingly congested world. They’re easier to park, cheaper to operate per mile and they consume far less steel, aluminum, plastic, rubber and energy to manufacture, per vehicle.

And fuel efficiency? Based on the Department of Transportation’s estimated 50-mpg average for motorcycles versus 22 mpg for cars, bikes consume 56 percent less fuel per mile traveled. If Americans would use a motorcycle instead of a car for one out of every 10 drives we make, we’d save an estimated 4.2 billion gallons of gasoline annually.

But we, as the faithful, already knew that. What may be less apparent is the increased use of motorcycles as regular conveyances.

According to the most recent (2003) bike-use data compiled by the Motorcycle Industry Council, roughly 25 percent (1.67 million) of the 6.6 million on-highway bikes (including dualsports and scooters) in the U.S. were being ridden as primary transportation for most of the year. And another 400,000 (6 percent of the total) or so were doing primary-trans duty for at least part of the year.

Sure, the numbers are paltry compared with an estimated 90 million cars and trucks clogging the streets and parking spaces. But the good news is the use of bikes for commuting and general transportation has been on the rise, keeping pace with the yearto-year sales boom the industry has enjoyed since the 1990s.

And the MIC sees this trend continuing.

My own lame excuses for choosing four wheels instead of two are no doubt rooted in nearly 30 years of the weekend-ride mentality which, when I’m on the bike, has me avoiding heavy traffic as urgently as I avoid liver at a dinner buffet.

In the past when my routes to work were on secondary roads,

I used my motorcycles to commute two or three days each week from mid-April through late November. I rode in most weather, saved a mint on gas and I always arrived at the office invigorated.

I want to return to that scenario. Unfortunately, the quickest route to my current job crosses 30 miles of Detroit’s most crumbling, frenetic freeways. It’s intense combat-commuting all the way. Braving the perils of inattentive Expedition drivers, bike-devouring potholes, bridges that shed hunks of concrete like dandruff, and untold alien objects in the road-fancy hitting a diesel engine block that’s fallen off a flatbed in the middle of l-96?-are not on my Top 10 Motorcycling Experiences list.

Certainly America’s auto-centric culture presents challenges to making motorcycling part of the mobility regime. But it can be done with commitment and creativity.

It took the shock of last summer’s crazy-high fuel prices to reawaken me to the major asset bikes can be beyond my hobbyist’s norm. First, while riding in Britain on my way to the Manx Grand Prix on the Isle of Man, I was astounded to pay the equivalent of $6.20 for a gallon of petrol. No wonder the Brits, Europeans and Japanese, all of whom are used to such prices, regard the motorcycle as a valuable part of their transportation systems.

Filling up the 5.3-gallon tank on the BMW R1200STI was piloting cost two-thirds as muc as filling up the 17-gallon tank on my Dakota pickup back in the States. Ouch.

But the 1.2-liter Beemer, loaded with my 195 pounds and hard panniers packed to the bursting point, averaged 51 mpg during the 1100-mile trip. B comparison my truck, with its 3.9-liter V-6, barely manages 18 mpg unloaded on the highway.

Then came Ouch #2. While I was soaking up the “real roads” racing on the Island, Hurricane Katrina was hammering the Gulf Coast and shutting down a lot of U.S. oil-refining capacity in the process. By the time I’d returned in early September, a gallon of regular gas had skyrocketed to $3.80 at my local station. Even as U.S. fuel prices subsided to pre-Katrina levels, the price of tanking up my truck has more than doubled in the past 18 months.

Volatile fuel prices help make 50 mpg an alluring feature for any vehicle. Compared with overpriced hybrid cars that won’t return my investment for years, the payback from a bike is almost immediate.

I’m no alarmist, but I see a future where energy-particularly its cost and strategic implications-will increasingly occupy the forefront of our lives. Add greater road congestion and parking headaches, and it’s clear that motorcycles can play an important role in alleviating these issues, as they do today in other parts of

the world.

What will it mean for daily riders? We’ll be forced to get more involved in local and state lawmaking, to insure motorcycling remains an accessible, affordable commuting option. That includes preserving and expanding HOV lane use. Securing protected parking for bikes in public and private lots. Equipping traffic signals with sensors that recognize a bike versus a car. And offering incentives such as reduced bridge and highway tolls to those on two wheels.

I’m not kidding myself that even a drastic, sustained bump in fuel prices would turn my freeway into a sea of bikes, or that my town will ever allow motorcycle parking on its Main St. sidewalks, as is common in Paris and London and Tokyo.

But opting for the bike and not the steel cage will get us part way there.

In the meantime, I’m checking the local map for a longer, albeit more bike-friendly route to work. —Lindsay Brooke

Lindsay Brooke is the author of three books on the history of Triumph. When he’s not wrenching his bevel-drive Ducati or Norton Commando, he’s covering the auto industry for Automotive Engineering International magazine in Detroit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWorld's Fastest Indian

February 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBeemer Report Card, Summer Semester

February 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUntying Knots

February 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2006 -

Roundup

RoundupSub Culture

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

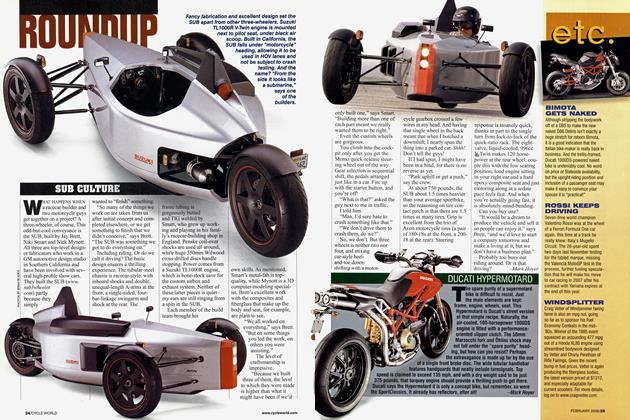

RoundupDucati Hypermotard

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer