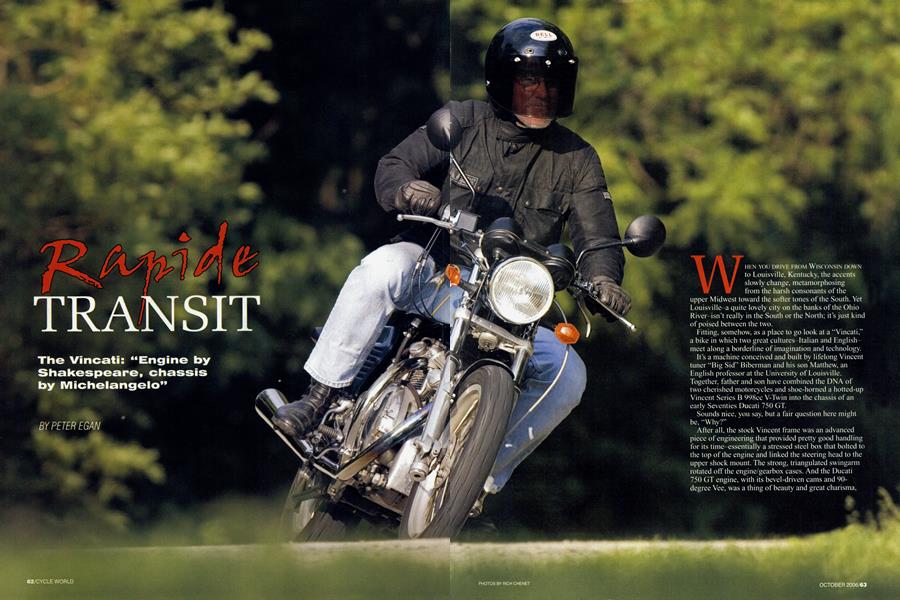

Rapide TRANSIT

The Vincati: "Engine by Shakespeare, chassis by Michelangelo"

PETER EGAN

WHEN YOU DRIVE FROM WISCONSIN DOWN to Louisville, Kentucky, the accents slowly change, metamorphosing from the harsh consonants of the upper Midwest toward the softer tones of the South. Yet Louisville-a quite lovely city on the banks of the Ohio River -isn’t really in the South or the North; it’s just kind of poised between the two.

Fitting, somehow, as a place to go look at a “Vincati,” a bike in which two great cultures Italian and Englishmeet along a borderline of imagination and technology.

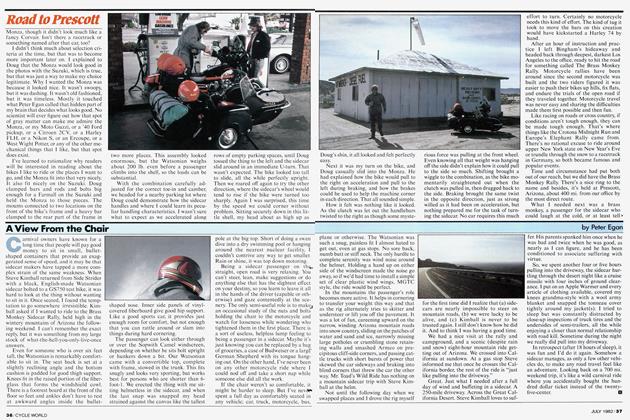

It’s a machine conceived and built by lifelong Vincent tuner “Big Sid” Biberman and his son Matthew, an English professor at the University of Louisville. Together, father and son have combined the DNA of two cherished motorcycles and shoe-horned a hotted-up Vincent Series B 998cc V-Twin into the chassis of an early Seventies Ducati 750 GT.

Sounds nice, you say, but a fair question here might be, “Why?”

After all, the stock Vincent frame was an advanced piece of engineering that provided pretty good handling for its time-essentially a stressed steel box that bolted to the top of the engine and linked the steering head to the upper shock mount. The strong, triangulated swingarm rotated off the engine/gearbox cases. And the Ducati 750 GT engine, with its bevel-driven cams and 90degree Vee, was a thing of beauty and great charisma,

never mind the occasional rod-bearing weakness. Why bother with a frame and engine swap on these two timeless classics?

“Good question,” Matthew Biberman tells me. “I guess I wanted the Vincati for a long trip-that’s my dream. I’ve got a 4-year-old daughter, and someday I’d like to take her on a road trip. Also, I grew up riding a Ducati 750 GT. With the Ducati, you get a more supple ride and a nicer long-distance bike. You could see going to Daytona or Sturgis on it. Better seat and riding position with a passenger and luggage. It’s

a question of how you’ll feel on day three or four of a road trip. You’ll enjoy life more on a Vincati.”

Big Sid seconds that opinion: “The Ducati GT chassis is the most comfortable conveyance for the human body I’ve ever been on.”

Okay. But why the Vincent engine? What do you gain over the 750 GT motor?

“The Vincent engine is more muscular,” Matthew says, “and more relaxed, with bigger hits of power.”

Fair enough, and it’s also extremely beautiful, I think to

myself as the Bibermans roll open their garage door and reveal the Vincati. Sitting on its centerstand, decked out in silver-blue (a ’67 Corvette color) with gold trim, the bike looks spectacular.

Allan Girdler once famously remarked that the Vincent Twin always looked as though it had been put in its frame with a whip and a chair. Well, that effect is not lost in the Ducati chassis. The Vincent motor has a combination of ¡I beauty and wickedness, a seriousness of purpose, that’s simply beyond compare. It looks like an engine that might eat young or suddenly jump out of there and sting you to deaf It has not just beauty, but deadly beauty. The kind that se: land-speed records at Bonneville.

Once I take my eyes off the silver-blue Vincati, I look around the garage and realize I’m in Vincent Central. Park« alongside the Vincati are a 1951 Series C White Shadow, a 1950 Series B Vincent Meteor and an Egli Vincent. Fittingly, W the two modern bikes in the garage are Sid’s 2000 Suzuki ,r SV650 and Matthew’s 1989 Honda Hawk GT-in case you wonder what Vincent guys ride when they don’t feel like g¡ adjusting anything.

As the a morning White Shadow warm-up, for a the ride Bibermans around the insist neighborI take H hood. They live in a pretty suburb of Louisville with post-war ranch houses set well back from shaded streets, the green trees heavy with early summer. A couple of blocks away is a street that forms a big oval, once a famous horse-racing track where the first Preakness was held. What more fitting place to warm up a Vincent? I do as many laps as I can without having the police arrive, then return to the driveway. I used to have a 1951 Black Shadow, and I’d almost forgotten how serene and relaxed a Vincent can be.

And this is a lovely example.

Now it’s Vincati time.

Matthew wheels it out and begins the start-up ritual.

The Vincati has a Bosch electric starter mounted under the engine, a French-built kit that drives the engine through the kick-start gear. But Matthew doesn’t just hit the electric starter and go. He likes to save the starter and battery, he explains, for re-starting the bike when it’s warmed up.

He turns on the fuel taps, turns both chromed choke levers, pulls in the compression release and kicks the engine through a few times. Then fiddles with a few toggle switches for the 12-volt coil ignition (from a late Series D Vincent) and gives it eight or nine kicks before it roars to life and settles down into a nice pulsing idle.

I do some laps around the erstwhile horse track while a few lawn-raking neighbors glare. Apparently, they haven’t forgotten my recent visit with the Shadow. Then I head into downtown Louisville, following Matthew’s Vincent, while Big Sid and photographer Rich Chenet follow in a car.

In traffic, the Vincati is pretty civilized for a machine that-on paper-could be a cantankerous beast. The clutch is moderate and normal, the gearbox shifts with a well-oiled weighty click-though you want to find neutral before you stop rolling (shades of my old Shadow). Also, the electric starter mechanism prevents the bike from rolling backward, even with the clutch disengaged, while you’re in gear, so U-turns require foresight. The engine is pretty tractable, if a bit cammy at stoplights. It wants to spit back and quit now and then. Sid later tells me they’ve already decided the aftermarket racing cams are too extreme and plan to put a set of better-idling factory Lightning cams back in as soon as possible.

Still, the bike pulls nicely at low rpm and comes on like

gangbusters above 3000 rpm, flinging the bike down the road like the hand of God. It is indeed muscular as no 750 GT engine ever was, and it makes big power everywhere.

Getting into the restored red brick neighborhoods of the old industrial downtown, we pull over for photographs at a place called The Bluegrass Brewing Company, a local micro-brewery and pub. A friendly brewery manager named Chris MacGilvray (who turns out to be an avid motorcyclist) invites us to use the back alley to shoot pictures, then invites Sid and me into the pub to get out of the summer heat while Chenet clicks away on his camera.

Just after we sit down, Chris comes into the pub, smiling. “You won’t believe this,” he says, “but the radio station we have on out in the warehouse-WFKP-just played Richard Thompson’s 1952 Vincent Black Lightning. No one here requested it. They just played it.”

“What are the odds?” I ask.

Sid shakes his head and smiles. “Did you know MacGilvray is the name of an early owner of the 1953 Rapide that provided the engine for the Vincati? I should do a book on this bike. The whole project has fate and mystery in it.”

“How so?” I ask.

While the ceiling fan ticks overhead and we drink ice water from the bar, Sid tells me the story, complete with ethereal visions.

He had heart surgery five years ago, at the age of 72, and almost died in the hospital. But as Sid tells it, “At the gates of heaven, Philip Vincent said, ‘You’re going back; you’ve still got some engines to build.’ ”

As he lay in the hospital, Sid decided that building a Vincati would be a good rehabilitation project. “As it turns out, the pieces were just waiting for me,” he says.

Sid, however, is a little sensitive about the origin of those pieces, because he’s afraid both Ducati and Vincent buffs will be put off by the apparent pirating of parts to build the bike. He need not worry, though, because no animals were harmed during the making of this movie. The engine was given to Sid by an old friend who had taken it out of a 1953 Rapide so he could use the chassis to build a single-cylinder

Vincent Comet to run at Bonneville.

The Ducati half came from a race shop near his old home in Norfolk, Virginia.

A man who was building a vintage racer prepped the whole chassis, then decided to buy a hand-built Italian frame and put his 750 GT race engine in that. So Sid was able to buy a rolling chassis, complete with Sun 18-inch alloy rims, modern Brembo brakes and new Avon Roadrunner tires. “Already done! Tell me that ain’t fate! I was given the motor and found the frame.”

The engine was rebuilt by some mastermachinist friends of Sid’s from Portsmouth,

Virginia, who worked with him for decades back when he had his own shop in Norfolk.

They refuse to take individual credit, he says, and just want to be known as “The Midnight Crew.”

Sid describes the motor as “full trick.” It has ported heads, Specialoid 10.06:1 racing pistons, lightened flywheels and hot cams. Rods are standard but shotpeened, and the crank rides in competition INA roller bearings with silver-plated cages. The crank has been rebalanced from 46 to 60 percent, “So it feels like you’re sitting on a sofa through the seat, tank and bars, with only a mild pulse at the footpegs,” Sid says.

Carbs are reworked 32mm Amal Mk I concentrics off a Norton 850, and there’s a Neal Videan primary drive kit with a Triplex chain and double springs on the cush drive. The V-3 Videan clutch uses Kawasaki pieces, and the alternator is made by Alton, of France. Standard Vincent 2-

into-i exhaust headers flow into a Conti replica muffler from Australia. "How fast do you reckon this bike should go," I ask Sid. "About 140 mph in present tune, and maybe 150 if! put on the Lightning twin pipes and intake rams."

Engine straightforward installation because was relatively the engine and frame naturally line up, sprocket-wise (and, interestingly, both engines-Ducati and Vincent-weigh almost exactly 200 pounds), but making the mounts was not easy. The Ducati frame’s front downtube had to be cut away, and the cylinder-head motor mounts had to be lined up and tack-welded onto the frame, then reinforced. Downtube pieces were cut

up and welded in laterally to brace the upper frame.

Most of the templates and drawings to do this came from an Australian named Don “Hendo” Henderson. Sadly, he died from melanoma not long after Sid sent him photos of this bike. “A sweet guy everybody loved,” Sid says.

“Are there other Vincatis, then?” I ask.

“Oh, yes. Ours is the sixth in the world; the other five were built in Australia.”

I ask why so much Australian Vincati activity, and Sid explains that there was a big craze for Vincent-powered racing sidecars in Australia, while Ducati 750 GTs were very popular among roadracers. The Ducati engines blew up, and there were lots of outmoded and bent old Vincent sidecar

rigs lying around. Voila! A natural combination.

And it feels like a natural corn bination later that afternoon as we

head out of the Louisville traffic and into the ever-emptier roads that wind through the famous Bluegrass Country east of the city.

The Vincati is acceptable in traffic, but it really likes to be out of town. Turning only 3000 rpm at 70 mph, it muscles down the road with a relaxed, easy gait, but when you roll the throttle on it just lunges forward and goes faster. And then faster, with no sense of an end in sight. On the highway, it sounds like a 50-caliber machine gun with an unlimited supply of ammo, spitting out big rounds with a steady, hardhitting beat.

The riding position, as Big Sid says, is perfect, and the bike turns in easily and sweeps through fast corners with rock-solid stability. It’s an easy, civilized bike to ride, except perhaps for that morning kick-start procedure-after which

the electric starter actually does work. Otherwise, the bike really is the sort of thing you would like to ride-and listen to-all the way to Daytona or Sturgis. It’s harmonious and well-sorted, as if this frame and engine were intended for one another all along.

So is this the last of the line?

No, Matthew tells me. He hopes to build a run of 10 Vincatis, using new replica frames, with replica engines built from all-new components by Colin Taylor in England. “The price per bike?” I inquire hopefully.

“One hundred thousand dollars,” Matthew says.

Hmmm. Well, maybe I’ll get a 750 GT someday. Yeah, that’s the ticket.

Meanwhile, Big Sid has realized his dream of building a Vincati with his son, only three years after Phil Vincent sent him back from the gates of Heaven to do more good work.

And Matthew has in his garage, “The Platonically Perfect Custom Classic,” as he so eloquently puts it, ready to take that trip with his daughter. All’s well.. .as the Bard says. E3

For more photos of the Vincati, visit www.cycleworld.com