Passages

UP FRONT

David Edwards

IN LIFE, I DOUBT THAT OTIS CHANDLER, Larry Grodsky or Johnny Chop ever met. They didn’t exactly run in the same circles.

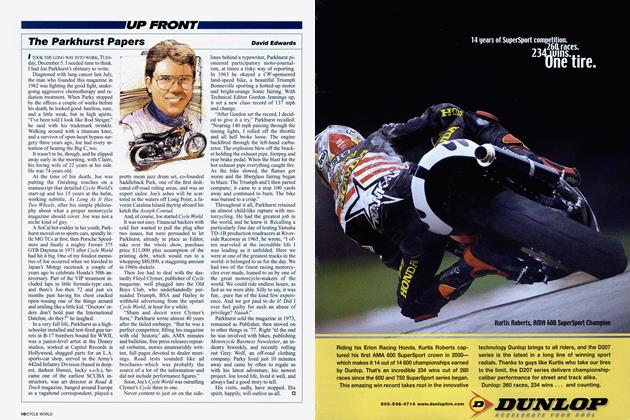

Chandler, 78, was the multi-millionaire ex-newspaper publisher who amassed one of the world’s finest collections of motorcycles. Grodsky, 55, through his long-running magazine column and his riding schools, was the best known motorcyclesafety expert in the country. Chop, 34, built some of the purest Harley-based customs of recent times.

All three men died this past spring.

There is more than a little irony in this Chandler, for all his money and a lifel zeal for fitness, could do nothing to stop the onslaught of Lewy disease, a degenerative disorder that combines the worst effects of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Seven months after diagnosis, he was gone. Grodsky, who penned Rider magazine’s “Stayin’ Safe” column for 18 years, was riding home from the International Motorcycle Safety Conference when he collided with a deer on a deserted West Texas highway and died instantly. Chop, always a man with a ready smile, a quick quip and a big heart, was felled by a bum ticker.

To say that Chandler was born to a life of privilege is true-his family owned the Los Angeles Times-but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Norman Chandler insisted his only son start at the bottom, which meant as a boy Otis shoveled fertilizer in the family citrus groves. Neither was his higher education at Stanford University particularly plush. A tight allowance meant Chandler’s only mode of transportation was half-interest in a decidedly secondhand Knucklehead Harley. When he started at the Times in 1953 it was as an apprentice pressman on the graveyard shift making $48 a week.

Seven years later, having worked in every department at the paper, 32-year-old Chandler was named publisher. It was not exactly an ideal posting; the Times was a sad joke of a big-city newspaper. Over the next 20 years, though, Chandler would turn it into one of the world’s great newsgathering organizations, with nine Pulitzer Prizes to its name and a two-fold increase in circulation.

And then he quit.

“Otis is going surfing and he’s never coming back,” one of his editors said at the time. An Olympic-class shot-putter in college, Chandler was also an accomplished long-boarder and serious biggame hunter, but his post-newspaper years were increasingly filled with cars and motorcycles. At one time his 45,000square-foot Vintage Museum of Transportation and Wildlife held 130 bikes of eclectic variety-everything from brassera classics to perfect replicas of the “Captain America” and “Billy Bike” movie choppers to a Honda RC30 repli-racer. Lately, Chandler had refocused the collection and pared it down to 50 examples of mostly early American models. Fifteen of his bikes were part of the Guggenheim Museum’s landmark “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit.

“If Otis Chandler hadn’t existed, Hemingway would have created him,” a reporter once wrote, which may be the best epithet ever.

Larry Grodsky prevented (well, delayed, hopefully ’til old age) the need for epithets. Hundreds of thousands of riders read his safety advice over the years, and since 1980 some 5000 clients have been educated at his Stayin’ Safe Motorcycle Training school, cornerstone of which are twoand three-day backroad tours. The school (www.stayinsafe.com) has abbreviated its schedule following Grodsky’s passing but plans a full selection of courses in 2007.

On his way home to Pittsburgh from the safety conference in California, riding an ex-police Kawasaki he had just purchased, Grodsky detoured to Big Bend

National Park in Texas to shoot photos for a feature story. He had planned to stay the night in nearby Marathon but there were no vacancies in the town’s two hotels, so after dark he pushed on toward Fort Stockton, 60 miles distant. It was on Highway 385, a lonely two-lane, that Grodsky and the deer tragically crossed paths.

“We really miss him,” said Rider’s Editor Mark Tuttle. “He was a unique character, a neat guy with a quirky personality and a laid-back attitude that concealed unbelievable knowledge and skill. His special ability was in taking a complicated subject that could easily put you to sleep and giving it a fresh, in-depth treatment that provided readers with food for thought. He had an enormous following. He’s left a big hole to fill.”

Likewise Johnny Chop, born John Vasko in 1971. Young Johnny progressed from customizing Hot Wheels toys to bicycles, then hot-rods and motorcycles. Millions of television viewers met him on the “Biker Build-Off” series, where he functioned as right-hand man to Japanese-born Chica, often translating the boss’ cryptic grunts for the camera.

Chop was a talented craftsman in his own right, turning out clean, 1960s-influenced, Frisco-style choppers. Refer to him as a “master builder,” though, and you’d risk having a wrench flung in your direction. “A pair of pliers and a blowtorch, that’s all you need,” he liked to say, downplaying his considerable skills. Truth is, his bikes were beautifully done and simple, the antithesis of the gaudy, trite, formulaic customs that TV has unfortunately spawned.

“He had an incredible eye for style, for what was cool, not just popular,” said builder Roland Sands, who collaborated with Chop on several projects. “He knew cool.”

He also knew what was important. As a teenager, Chop had received a heart transplant. Though he didn’t dwell on it, he realized his chances of drawing Social Security were none too good. Last March, after a couple of days of not feeling well, he headed to the hospital but there was nothing the doctors could do.

“A lot of us take life, take good health, for granted,” said Sands. “Johnny never did. He lived every day like it was his last-because maybe it was.”

If there’s a lesson here, that’s as good as any. As Johnny would say, “Ride fast, ride unsafe.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue