SPRINGER

RACE WATCH

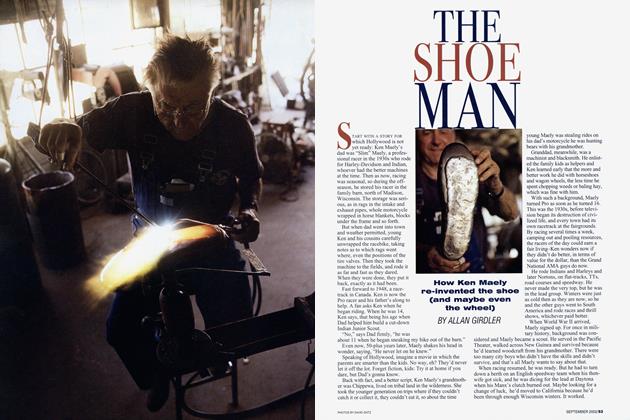

The Life and Times of a Natural Champion

ALLAN GIRDLER

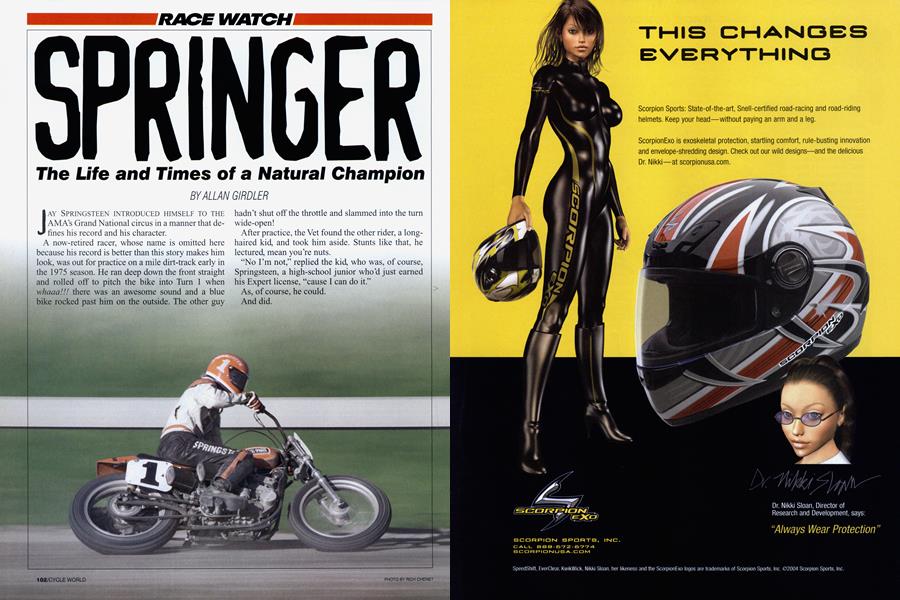

JAY SPRINGSTEEN INTRODUCED HIMSELF TO THE AMA’s Grand National circus in a manner that defines his record and his character.

A now-retired racer, whose name is omitted here because his record is better than this story makes him look, was out for practice on a mile dirt-track early in the 1975 season. He ran deep down the front straight and rolled off to pitch the bike into Turn 1 when whaaa!!! there was an awesome sound and a blue bike rocked past him on the outside. The other guy

hadn’t shut off the throttle and slammed into the turn wide-open!

After practice, the Vet found the other rider, a longhaired kid, and took him aside. Stunts like that, he lectured, mean you’re nuts.

“No I’m not,” replied the kid, who was, of course, Springsteen, a high-school junior who’d just earned his Expert license, “cause I can do it.”

As, of course, he could, And did.

That was 1975, now is 2004, and 30 years of race reports won’t do the job we’re doing here, but even so, the beginning is important.

Jay Springsteen comes from industrial Michigan, the Flint area, from a bluecollar family with a love of sport. His dad liked motorcycles and his older brother raced. When he was young, Jay had a bone disease and wasn’t supposed

to run, so Dad made him a mini-bike. The fact the kid was racing before he could run says something in itself.

He was the hottest Junior in the country in 1974, clearly marked for big things. But the kid was as brash on the track as he was shy off of it. Harley-Davidson and Yamaha-well, make that Kenny Roberts on behalf of Yamaha-were locked in combat. Springsteen’s talent was obvious, but H-D’s racing chief was Dick O’Brien, a coach and a leader, but a man who felt it was the other man’s job to ask, and his to say yes or no.

Springsteen was too shy to ask for the job.

Instead, there were Michigan fans who knew the kid deserved a shot. One owned a T-shirt company, Vista-Sheen by name, and a top tuner built Springsteen a Harley XR-750, painted in Vista-Sheen colors and emblems. This was good equipment-witness the fact that one of the team bikes, Ricky Graham up, was the

only Harley 750 ever to win the Houston TT, and that was nine years later.

The record shows Springsteen’s first win was in June, 1975, on the limestone Louisville half-mile. He won the next race after that, finished third in the series and was asked to join the factory H-D team.

More good luck followed. The 1975 champion was Gary Scott, who quit the Harley squad mid-season, leaving lead tuner Bill Werner free to wrench for Springsteen. It was, speaking modestly, a winning combination. They won the AMA Championship in 1976, repeated in ’77 and again in ’78.

These were good times. Springer was cheerful, brash and likeable, as good with the fans as any racer in history, and such a talent that even the guys who lost to him didn’t resent it.

Well, there was still a human element.

The AMA Grand National Championship was then awarded based on a series that included five types of races-shorttrack, TT, half-mile, mile and, yes, roadracing. It was an Olympic format and the winner had to be good at all forms of racing.

Harley-Davidson’s roadracing Twins had been put in the shade, along with the similar machines from Triumph, BSA and Norton, by Yamaha’s two-stroke TZ Four. H-D didn’t even bother to field entries for the roadraces. Before Springsteen hit the scene, “King” Kenny won the AMA title twice, putting the Yamaha two-stroke roadracers to good use. Springer won No. I without a roadrace bike...and Roberts left to conquer Europe. There are those who say this wasn’t mere coincidence.

Time for two anecdotes: As the team was setting up one Saturday for the following day’s race, O’Brien-the classic coach, don’t forget-noticed Jay drinking a beer.

“You’re breaking training,” O’Brien ruled. “Em fining you $50.”

“Make it $100,” Springsteen said. “I’m gonna have another.”

During the same time period, the other guy on the Harley team was Randy Goss, a quiet and determined rider who earned the No. 1 plate in 1980, but not an outgoing personality. The fans had the team’s pit under siege, everyone clamoring for Springer’s autograph, pictures and such, while Springsteen made a quiet point of steering people to Goss’ side of the table...and the bet is, not until now will Springer know anyone noticed.

At Springer’s peak, when he was all but invincible, leaving the rest of the field to battle over second place, he began to get sick. Not butterfly sick, but seriously, can’t-keep-it-down sick. Some days he’d win and get sick, other days he was too weak to even ride, while none of the usual medicines or diagnosis made a difference.

Harley-Davidson spared no effort or expense, gotta give ’em that. Springsteen went to doctors, hospitals, clinics and research centers. While the exact nature of the problem has never really been found, nor are the medical records public, some surmise is possible.

One report said that if you took 10 guys exactly equal to Springsteen in height, weight, muscle tone, aerobic fitness and so forth, and had them run a 100-yard dash, Springsteen would have won every time, because he would be the guy with the most drive, the will to win.

Second, add to that the outside pressure. The tabloid press has always liked to portray motor racing as a blood sport, fans eager for death and disaster, never mind that a legendary sportswriter, Paul Gallico, as far back as the 1930s found that when there was an accident, the fans got sick and went home.

No, Gallico wrote, what racing fans want is for their heroes to take chances...and win! We count on the racers to beat the odds, to do what we can’t do.

That understood, here we were at the Indianapolis Mile in 1982. It’s the main event, Springer is mid-pack, the rider in front loses it, they collide and Springsteen is thrown to the ground at 100 mph.

In the family section of the grandstands, Bill Werner’s young daughters burst into tears and race for the pits. Everyone who can get there heads for the pits. Springer is brought in. No broken bones, no blood, just a savage pounding over every inch of his body.

He stood there in pain and shock, while Werner and Springer’s then-wife Debbie eased his boots off and sat him down, and all around was a sea of faces, scores of fans who stood and worried. They meant well. But all they accomplished was making him wrench out of his leathers and into his jeans in public.

He limped away, leaning on his wife, and I realized there’s another side to being the hero, the man on whom we rely to perform another miracle 20 times each season.

Imagine that pressure and what it can do, and it seems a good bet that medical science would call Springsteen’s stomach problem, simply, riding his guts out.

Nor was that the only pressure.

Check racing history and, over and over, the champions have a finite time at the top. In music, they reckon top billing lasts seven years. What it would be in

racing isn’t as calculated as, say, Richard Petty, then Bill Elliot and now Jeff Gordon, guys who win time after time, rule the races and then one day it’s not as it was, never mind that the team and equipment and rules haven’t changed.

Psychic energy is the best term, and it seems as if the champions have it. But even they can take it to the limit for only so long, rewrite the song only so many times.

Meanwhile, we’re in the early and mid1980s. Jay and Willy-as insiders call Werner on days everyone isn’t calling each other “Jimmy” in response to clues I never picked up-are a team, working for H-D. Jay went winless in 1980, took a shorttrack and two miles in ’81, but was only eighth in points because he missed so many races. He came back in ’82 with five wins, but lost the title to Ricky Graham by two, yes two, points.

It was a different ballgame, so to speak. Jay invented the wide-open mile, but Ricky and new teammate Scotty Parker were not as crazy as Springer was, and they all had good equipment. Springsteen finished behind Goss and Graham in 1983 despite five wins, again because his bad days were as bad as his good ones were good.

Then, things got worse. Not medically, as one might predict, for when the pressure eased, when the fans no longer came up and asked Springer why he hadn’t won, his health improved.

Pause for a different problem. Any sports star from the pre-TV era has to wish he’d been born later, just in time for the million-dollar sign-ups. Further, motorcycle racing has never been big bucks, not now in comparison and especially not back then. That said, Springsteen was well paid by Harley-Davidson by the standards of the day. His dad served as business manager when Springer was finishing high school.

Springsteen Sr. was honest and careful, for sure. But there was at H-D at the time an executive with a tremendous head for business, an Ivy League education and the contacts that come from such a background. This exec was also a racer, good enough for a license and good enough to know how much better Springer was, and, of course, the Ivy Leaguer was a fan and tried to help the Springsteens manage the money.

No go. The Springer of those days was as leery of polished talkers as he was comfortable with the fans. The exec, who left H-D and founded an empire, still wishes he’d been able to help. Further to that, Harley-Davidson was treading on thin financial ice back then, what with the buy-back from AMF and the need to invest in the product.

And Springsteen wasn’t winning.

This was painful.

This was like being a guest in the home when a domestic fight breaks out. H-D has always been loyal, as much as possible, and no one doubted Springer was giving all he had. But he wasn’t winning, and money was tight.

Finally, Springsteen broke the awkward silence and said he wasn going to stay on the team. It had to be done, so he did it, and it hurt to look around the room and see the pain and relief on the faces of all concerned.

There was some sleight-of-hand here, as Harley dropped the full team and hired Parker to be an “outside contractor.” (Gossip: Parker’s contract said he could hire a tuner, provided the tuner was qualified. Parker hired Werner. H-D management objected, on grounds that Werner was already employed in another department. Parker’s attorney suggested the execs read the contract again, and Werner was hired-on his own time, of course-and the new team set new records.)

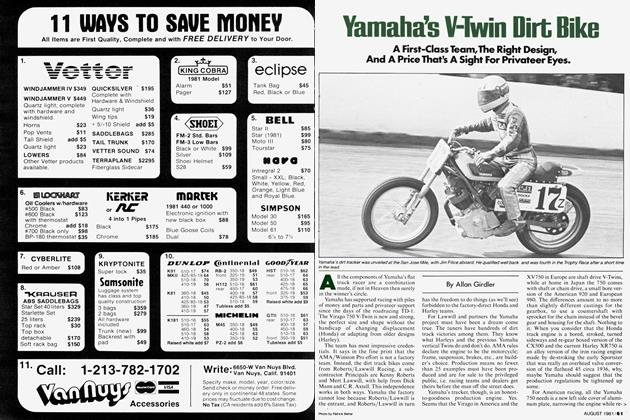

Pause here for what might have been: Yamaha’s domination of AMA roadracing discouraged the fans of the other makes, so the AMA created a new series for the outclassed four-stroke roadracers. It was called, no prize for guessing, Battle of the Twins.

O’Brien and retired racer Carroll Resweber dragged a lowboy XRTT from under the workbench and fitted it with an XR-750 engine posing as an XR-1000-it displaced lOOOcc and carried production numbers. Springer had earned his Pro roadrace license and rode the beast, nicknamed “Lucifer’s Hammer” by O’Brien, to an easy win in the series’ inaugural event at Daytona in 1983. (Second place that day was Jimmy Adamo, astride the best Ducati in the U.S. “Imagine,” commented Phil Schilling of Cycle magazine, “how many Italiophile hearts were broken here today.”)

The win gave an immense and appreciated boost to the folks at Harley, at a time when the doors were open on a dayto-day basis. Add to this the little-known fact that H-D Racing’s Pieter Zylstra had designed a for-real roadrace 750, a stacked opposed four-cylinder two-stroke.

The machine was never built because Harley has an honest tradition of not racing what it doesn’t sell, and, of course, money was scarce.

Even so, the record proves Springsteen had the talent to win roadraces against the best. If we put all these ifs together, we can’t not wonder if Springer could have gone the route of Roberts, Spencer, Lawson and Rainey, all the way to Kurtis Roberts and Nicky Hayden, and given the world lessons in what dirt-trackers can do on pavement.

Okay, we’ll never know. Too bad.

Meanwhile, back in the racing department at the corner of the old Harley plant on Juneau Avenue in Milwaukee, Parker and Werner were keeping the wins coming.

Springer still had talent and drive and fans and friends, notably Bill Bartels, a Los Angeles Harley dealer and once again, a man who’d done enough racing to know

how good Springsteen was. He picked up Springer’s sponsorship-which he still does-and others joined the program.

The talent was still there, witness his appearance in the series’ top 10 most years and his win of the Pomona HalfMile in 1992.

For a happy bit of fate, Springer was in Daytona when vintage roadracing arrived. He stopped to chat with Carl Patrick, a top engine builder who’d done work for Hourglass Racing, namely a couple of XRTTs. Jay said they looked great, might be fun, team owner Keith Campbell invited him to ride one, and he’s been a member of the team-okay, the star of the show-ever since.

In the same approximate timeframe, on a personal note, Springsteen went through a divorce, followed by a happy second marriage, and here we are in present time.

Despite rumors, Springer, at 47 years old, is still not retired. His 2004 program consists of riding the top dirt events, the Springfield Mile, for instance, and doing the AHRMA roadrace series for Hourglass. He lives in still-rural Michigan, in the house he built with his earnings from that first championship season. Springsteen has never been one for high living, no exotic cars or second homes or celebrity lifestyle. Daughter Amanda is in college not far from home, and dad is comfortable, has time for fishing and hunting-his best story about that concerns the time a bear contested his possession of the deer he’d shot-and he’s looking forward to the next race.

Meanwhile, at the time this was written, he was more interested in getting the !@#$%A&* circlip on the shaft of the pump of his boat’s engine than he was in the details of his career.

For the punchline here, we visit Nicky Hayden, the future MotoGP World Champion.

When Hayden came home from his first season on the world tour, someone asked him about the tactics of Max Biaggi, the fiery Italian rider who’s famous for crowding and using psychological tactics on rivals, especially new kids.

“I kind of enjoy it,” Hayden said. “It’s part of racing. Besides, compared to what Parker or Springsteen would do to you on a short-track, Biaggi’s a gradeschool move.” □