SERVICE

Some don’t like it hot

While watching supercross and motocross races this season, I’ve noticed that a lot of the four-stroke riders struggle to restart their machines after a crash, while two-stroke riders kick the bike once and are back to racing. Why is the new breed of high-performance four-strokes so much harder to restart while hot?

Adam Bartlett Dayton, Ohio

Numerous factors contribute to this, but the most relevant are: 1) A four-stroke’s greater mechanical friction, particularly cam lobes scraping across followers and pushing against the resistance of valve springs; 2) its longer effective compression stroke (a two-stroke squeezes the mixture only during about half of the upward stroke, after the piston blocks off the exhaust port, whereas a four-stroke closes its mechanical valves earlier); 3) the need for lower kickstarter gearing that can give the rider more mechanical advantage to help overcome factors 1 and 2; and 4) a four-stroke only produces one power stroke every two crankshaft revolutions, compared to one every revolution on a two-stroke.

What’s more, four-strokes are permitted as much as twice the displacement of two-strokes in the two main motocross classes. The 250 class allows up to 450cc four-strokes while the ring-dings are limited to 250cc. Even in the 125 class, the two-strokes can be no larger than 125cc but the four-strokes can be as big as 250cc. Add this all up and you get an engine that is harder to kick and turns over more slowly because of increased friction, larger displacement and lower kickstarter gearing, and that produces half as many power strokes for any given number of crankshaft revolutions. Considering all those factors, it’s amazing that a big four-stroke Single can be kickstarted at all.

A four-stroke Single kickstarts fairly easily when cold primarily because its choke/enrichener circuit dumps enough fuel into the cylinder that the sparkplug has no trouble finding something to ignite. But for the engine to run as crisply and efficiently as possible when warm, the mixture has to be significantly leaner; and when you combine that comparative leanness with the aforementioned slow cranking speeds during kicking, the amount of mixture that is drawn into the cylinder on each intake stroke is marginal-for starting purposes, at least. If everything works perfectly (the rider begins his kick with the crankshaft in the ideal position for maximum possible firing cycles; if he gives the lever a full, long kick; if the throttle is opened just the right amount), the engine fires. If any of those factors are off a bit, it may take numerous attempts to get the engine running.

By the way, this is not a “new-breed” phenomenon: Four-stroke Singles have been fussy kick-starters since the invention of ...four-stroke Singles.

A crooked Bandit

I have a 2004 Suzuki Bandit 1200S that I just bought, and it appears that the right fork tube is a little closer to me than the left. I know it sounds weird, but if I stop when I’m traveling in a straight line and don’t turn the handlebars in the least, it looks like the fork assembly is aimed slightly to the right, using the fairing and gas tank as reference points. The bike goes straight and handles well, but darned if it doesn’t look like the fork is pointing to the right. Rob Auerbach Littleton, Colorado

Assuming your new Bandit has neverfallen over, it’s possible, but not probable, that some crucial part of its chassis (frame, swingarm, one of the triple-clamps, etc.) was improperly manufactured. If so, your dealer has an obligation to diagnose the problem and repair it under warranty. It’s also possible that the fairing and gas tank are not exactly centered, which can make the front end appear to be out of line. it’s more likely that the rear wheel is properly aligned with the front wheel or fork tubes are twisted in the triple-clamps. If either is the case, you should be able identifia and rectify the problem yourself.

If the rear wheel is adjusted so it points slightly to the right instead of being on same centerline as the front wheel, the tire back end has to shift to the right for the bike to travel in a straight line.

This, in turn, requires the front end to be angled slightly to the right so that both wheels are on the same straight-ahead plane. That causes the right fork tube to reside a bit closer to the gas tank than the left tube when the bike is going straight. Getting the rear-wheel alignment in the ballpark is fairly easy. With the front tire aimed directly at the rear tire, place two long, perfectly straight boards alongside both tires, one on each side and as high as the chassis will allow. The boards should just touch both of the rear tire’s sidewalls, but because the rear tire is wider than the front, neither board should touch any part of the front tire. The distance between each front tire’s sidewall and its adjacent board should be exactly the same if the rear tire is properly aligned. If the distances are not the same, correct them by using the chain adjusters to re-angle the rear wheel accordingly.

On occasion, accurately aligning the rear wheel requires that you ignore the reference marks on the chain adjusters, which means the chain may end up marginally out of alignment. If this happens on your bike, you have to decide which is more important to you: proper chain alignment or accurate rear-wheel alignment. Personally, Ifavor the latter.

If the rear-wheel alignment is correct and your Bandit’s front-end problem is the result of fork tubes that are misaligned in the triple-clamps, here’s an easy, effective fix: Put the bike on its centerstand and loosen the axle nut, the pinch bolts on the axle and the pinch bolts on the lower tripleclamp. Stand in front of the bike, facing rearward, and straddle the front wheel with your legs, grasping the left handgrip with your right hand and vice versa. Then give the handlebars a sharp push to your right while using your legs to resist deflection of the wheel. Tighten all the fork hardware and take the bike on a short ride, observing whether the right fork tube is still closer than the left. With a bit of trial-and-error using this adjustment method, you should be able to get the fork tubes square with the front of the bike when the wheel is pointed straight ahead.

’Scoping it out

I’ve been riding for 20-plus years and just got a 2004 Ducati 998 Matrix. I never thought of asking this before, but if 70 percent of a bike’s stopping power comes from the front tire, and we steer with the front tire, why is the front tire smaller than the rear tire? Stanley LaPorta

Oxford, Connecticut

Excellent question, Stan, and the answer lies in the fact that the wheels of a motorcycle function as large, powerful gyroscopes. One of the fundamental rules governing the behavior of a gyroscope is that it offers resistance to any forces that attempt to change the plane of its axis. If you hold a spinning gyroscope in your hands with its axis (the equivalent of a motorcycle wheel’s axle) on a horizontal plane and simply move the axis up or down or forward or backward, the gyroscope offers no resistance to those movements, because you kept it in the same plane. But if you try to tilt the axis in any direction, which moves it out of its existing plane, the gyroscope resists.

A motorcycle’s spinning wheels offer that same kind of gyroscopic resistance, which is why they have significant effects on the way a bike behaves. On one hand, the wheels provide much of a motorcycle s stability because their gyroscopic effect resists any tendencies for the bike to lean, which would change the plane of its axles. And when the rider tries to steer the bike by turning the handlebar, which alters the plane of the front axle, the wheel resists then, too. The faster the wheel is spinning, the greater the resistance it provides. And the larger the wheel’s diameter, or the greater the amount of its weight that is concentrated nearer the wheel’s circumference, the more resistance it provides.

A motorcycle that is not designed to change direction quickly at high speed, such as a full-dress touring bike or a fattired cruiser, can afford to have a large and/or heavy front wheel. But a sportbike or roadrace motorcycle needs a bare minimum of front-wheel gyroscopic stability so it can steer quickly, and both wheels have to be light enough to allow quick changes in lean angle. The wheels can’t be too small in diameter, however, or they will be adversely affected by bumps and pavement imperfections.

On performance bikes, the front tire is narrower than the rear because the tasks of initiating and maintaining traction in a turn, as well as hard braking (which takes place mostly when the bike is vertical), can be accomplished with a comparatively small contact patch. The rear tire, however, has to deliver the engine s power to the ground, even when the bike is leaned over at fairly radical cornering angles. That requires a considerably larger contact patch, which the rear tire achieves simply by being wider than the front tire.

FEEDBACK LOOP

In response to Ken Hill’s letter (“gottasickmodifiedrd,” Sept, issue) regarding his Yamaha RD350’s high-rpm miss, I suspect the problem may be with the ignition’s breaker points.

I and some fellow racers used to compete on RDs, and when the bikes would fail to pull redline or start to misfire, we always checked the points first. They often had weak springs, which would allow the points to bounce at higher rpm and act like a rev-limiter.

David Wilson Posted on www.cycleworld.com

Good call, David, and thank you for reminding me that RD350s have points. Yes, those little contacts could very well be the source of Hill’s misfiring problem. If he has even the slightest doubt about their condition, he should replace them. They can be a little hard to find these days and cost more than they did when the bike was new, but anew set might turn his hopped-up RD into the pocket rocket he wishes it to be.

It’s been a long time since motorcycles rolled off the assembly lines with breaker points, and many of those machines have had their ignition systems updated over the years with aftermarket solid-state equipment. For that reason, I occasionally forget to mention the points when offering a reader with an older bike some engine troubleshooting advice. Thanks again.

Heavy breather

A moderate amount of oil continually fouls the air filter on my ’93 Harley Davidson 883 Sportster. I’m mystified to how oil can be coming from the carburetor. I’ve logged more than 31,000 miles on it, mainly around-town commuting, with the occasional long trip. The solution my local repair shop suggested sounds complicated and expensive, and has guarantee of resolving the problem. I can live with it but would rather not have to if there is a relatively simple and inexpensive solution. Do you have any advice?

Carl Holden Jacksonville, Florida

Actually, Carl, the oil isn’t coming from your Sportster ’s carburetor; it is emanating from the engine’s breather system, which vents vapors from the crankcase up through the rocker boxes and into the air-cleaner housing. If something causes those vapors to contain excess oil, the natural suction of the intake system will draw a lot of that oil into the filter element.

Generally, this condition is the result of either of two problems: worn piston rings or a failure in the breather system. Worn rings can allow some of the pressure of compression and combustion to leak past, creating excessive turbulence in the crankcase. When that turbulent air exits through the breather system, it carries with it more oil than normal, which eventually accumulates in the air filter. Worn piston rings usually-but not always-also cause the engine to burn oil, so if your Sporty puffs exhaust smoke, the problem is most likely with the rings.

Another possible cause is a little one-way rubber valve, called the “umbrella valve,’’ in each rocker box. When crankcase pressure is high, which occurs when either of the pistons is on its downstroke, that pressurized air is vented up past the umbrella valves and into the rocker boxes, bringing with it a miniscule amount of oil mist. The air and oil then separate, with the air exiting through the breather into the air filter and the oil returning to the crankcase via a tiny drain hole. Then, the upstroke of the pistons creates negative crankcase pressure that sucks the umbrella valves closed and helps draw the oil down into the crankcase. But if the valve hardens and distorts, which it tends to do over time, it can’t seal properly, and that reduces the amount of crankcase suction available to the oil drain hole. And without that assistance, the oil cannot drain back to the crankcase quickly enough. It then accumulates in the rocker box, and some of it gets into the breather passages, where it is then transported out into the air cleaner, eventually saturating the filter element.

The cure here is relatively simple, involving removal of the rocker boxes and replacement of the umbrella valves. But if the rings are at fault, you re faced with an expensive top-end overhaul.

More power, commander

I have a 2003 Suzuki SV1000, and the only modification I’ve made to it was to install Yoshimura RS-3 race slip-ons. It still has the stock air filter, but since the bike runs leaner now, is it necessary to install a Power Commander to optimize the fuel-air ratio? The PC for my bike costs $332, so I’m wondering if it’s worth the expense. Sean Applebay

Posted on America Online

We have never tested or even ridden an SVI000 fitted with RS-3 race mufflers, so I can’t offer you any first-hand advice about the effect of those particular silencers on engine performance. In our August issue, we tested an SVI000S equipped with Yoshimura Tri-Oval Street Slip-ons and found they had no measurable effect on performance, either good or bad, but those mufflers are much more restrictive than the RS-3 race models.

Chances are that your SV is, as you imply, running somewhat lean, but probably not enough so to hurt the engine. The bikes come from the factory already programmed for lean air-fuel ratios, especially at smaller throttle openings, and the installation of a freer-flowing exhaust tends to lean out the mixtures even farther. If your SV still runs crisply and shows no signs of excessive leanness (hesitation, poor throttle response, pinging, surging, etc.), you probably can continue to ride it without concern about engine damage. But if your SV exhibits any of those lean-mixture symptoms, you would be well-advised to ante up for the Power Commander.

Actually, even a bone-stock SV1000 can reap noticeable performance benefits from a proper fuel-injection remap. Besides, you already have somewhere in the neighborhood of Nine Large tied up in your SV; spending another $300-$400 to enjoy all of the bike ’s performance potential seems like a worthwhile investment.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help.

If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com, or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Letters to the Editor” button and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

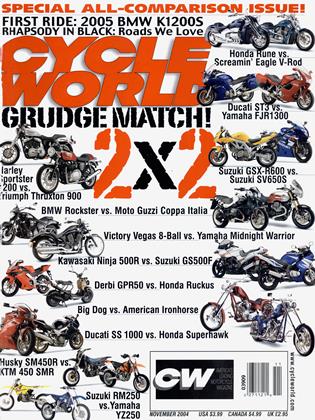

Up Front

Up FrontThe Accidental Sport-Tourist

November 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKtm Unplugged

November 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBigger Big Bangs?

November 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2004 -

Roundup

Roundup2005 Bmw K1200s: Too Fast For the Autobahn?

November 2004 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Goes To Motogp

November 2004 By Bruno Deprato