Harley-Davidson Sportster 1200 Roadster Vs. Triumph Bonneville Thruxton 900

November 1 2004 Allan GirdlerHarley-Davidson Sportster 1200 Roadster Vs. Triumph Bonneville Thruxton 900 ALLAN GIRDLER November 1 2004

Harley-Davidson Sportster 1200 Roadster vs. Triumph Bonneville Thruxton 900

Clash of the not-quite-conventionals

ALLAN GIRDLER

CANCEL TIlE CLICHÉS AND ALL THAT STUFF LEARNED IN high school for a moment and consider: Just exactly why is it we can't compare apples and oranges?

No, seriously. Both are fruits, they grow on trees, they can be eaten by hand and made into jellies, jams and juice or sliced into segments. Their similarities at least equal their differences. What it comes down to is, which meets your needs, which do you prefer?

And the point?

We’ve called this meeting to compare Harley-Davidson’s Sportster 1200 Roadster with Triumph’s Bonneville Thruxton 900. Continuing the parallels, both models are new this year, and both are powered by two-cylinder, aircooled engines. They both come from companies founded a century ago, albeit one may not be quite as old as they like to say and the other left the building for a couple of years.

Both makers offer larger and smaller machines, and the Thruxton 900 and XL1200R are both upgrades, souped versions of a basic bike. Which is a long way from saying the Thruxton and the Sporty are peas from the same pod, ’cause they’re not.

Starting in alphabetical order, the Sportster here is as close as the revised XL line comes to Sport. The R in those initials stands for Roadster, as against the other side of the XL line, the XLC Custom, which is a cruiser version. Keeping with new and old traditions, the XLR has an updated version of the harnean air cleaner, an enlarged 3.3-gallon fuel tank and the staggered dual exhaust

pipes made fashionable by the XLR (a real racer; ask your dad) way back in 1958. And, of course, keeping the record clear here, the new XLR has the rubber engine mounts that keep the V-Twin’s shakes and vibrations away from the bike’s occupants.

Triumph’s new sportster (not that they’d ever use the term, lower case or not) takes sport tö the edge of the racetrack. The name comes from a fabled and successful production racer built and sold in limited numbers, 1964 through 1966. The original Thruxton was named for an English track, and inspired scores of souped café-racers, at home and abroad.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPORTSTER 1200 ROADSTER

$8495

Ups

Rubber engine mounts! Dual front disc brakes Still a Sporty

Downs

Engine mounting system and reworked drivetrain add weight Clunky gearbox No toolkit

Just as Harley re-invented the Sportster, so did Triumph revive the Bonneville, the parallel-Twin that turned the make into a household word for several generations. The Bonnie’s 790cc engine has been bored to 865cc, rounded off to 900 in the brochure. Compression ratio has been raised, the camshafts have hotter timing, there’s a new exhaust system minus the clumsy kink, plus upswept mufflers.

The Thruxton has a shorter wheelbase, steeper rake to the fork, longer shocks and a smaller 18-inch front wheel, all in the interest of quicker, sharper handling. Fenders are shorter, and the passenger section is covered with a plastic cone that looks just like the humps on the proddy racers of 40 years ago.

Most radical feature is the rider’s posture. The bars are clip-ons, pegs and pedals are rearset, so the rider is crouched, hunched over the bars for less wind resistance at speed, tucked in aft of what must be the largest headlight on the market.

Not to hand out conclusions before their time, but when the Thruxton and the XLR were parked in front of, yes, the café where the bikers gather, everyone who looked remarked on what a skillful restoration the Triumph had undergone, and no one noticed that the XLR is new, new, new. In short, both Triumph and Harley-Davidson design teams have hit their targets, dead-nuts on.

To say that both bikes get equal points because both look exactly right isn’t to say they are alike; they aren’t. First and most obvious, the XLR is a bigger motorcycle. Not simply in engine size, but the Harley hits the road at about 100 pounds more than the Triumph. Bulk is the price the XLR pays for progress; well, make that change and improvement in the sense of reduced vibration.

Not that big is merely weight. The XLR’s wheelbase is nearly 2 inches longer than the 900’s. The Harley’s handlebars are motocross-class, fully 32 inches grip tip to tip. The Triumph’s clip-ons span only 26 inches. In context, as in a two-person streetbike, two cylinders and so forth, lighter has to be easier on brakes and tires and fuel, so the Triumph gets the nod here.

Just as clearly, the Harley is quicker. In roll-ons from 40 mph, the speed at which the contestants are comfortable in

top gear, the Triumph rider gets to hear what Chuck Berry called “That Highway Sound,” the irregular backbeat of the big V-Twin pulling away toward the horizon. We aren’t talking trouncing here, but the larger motor and its extra torque rules the performance tests, bulk or no.

As mitigation here, the Triumph is more nimble. It is lighter, and shorter, with more cornering clearance. And while neither machine is a club racer, mountaineering comes easier, as in equal speed with less work and worry.

With the quantified sections of the report card filled out, we come to the less tangible: Are there odd little notes, stuff the panel remarked, pro or more likely con?

Yup.

The XLR’s are more mechanical. The narrow V-Twin’s inherent vibration has been dealt with, if not tamed. The surprise is that in this XLR there was a sour spot in the engine’s revs. From 3000 to 3200, the grips and pegs vibrated-sorry, but it’s true.

The revised drivetrain is smoother and more powerful than the earlier XL Evo, but for some reason, downshifts in the lower gears, at low revs and slow ground speed, clunk. Downshifts are smoother and quieter as speeds pick up and the clunk, like the sour spot in the powerband, can be ridden around. And this flaw may be more noticeable because the Triumph’s are lighter and smoother all the time, but still...

On the Thruxton side of the debit, Triumph has taken the worst page out of the Harley book: There is no toolkit.

What there is is an Allen wrench. It’s stuck behind some wires beneath a sidepanel that’s held in place with a fastener that the book says can be turned with a coin. And p’raps it can be, by those with forearms like Popeye.

On a daily basis, the Thruxton is commendably narrow. Even so, the cylinders are side by side and a rider of less than 5-foot-10 will feel the heat in summer conditions a mile or so down the road. How hot? Close to, say, brushing against an exhaust pipe.

Revisiting the subject of character for a sec, the Triumph’s pipes are chromed and bare and turned color quickly. The Harley’s are shielded with chrome panels and don’t change color. Folklore holds that Harley owners hate any sign that their cherished bike has actually been on the road while Triumph owners brag on miles at speed; so again, both design teams have done their jobs.

TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE THRUXTON 900

$7999

Ups

More than a styling exercise Upswept exhaust captures the look, if not the sound Smaller and lighter...

Downs

...but not quicker Racing crouch not so hot ’round town A girlfriend will tolerate a day’s ride, a wife won’t

Back with quirks, the Thruxton’s main shortfall, its limit as a mainstream motorcycle, is part of the design. The Thruxton is a demanding bike to ride. The crouch is awkward in town, hard on the wrists and back. They did this on purpose, and if you don’t like it there’s always the plain Bonneville.

This may be a win-win comparison test. The XLR is solid without being fat. The Thruxton is nimble, agile without being fragile. The Harley pulls like a train. The Triumph revs like a racer. Run the XLR through the gears, settle back...and hey, there’s another gear left. Do the same with the Thruxton and you’re in top gear before you know it.

What we have here, then, is two divergent paths, specialized if not quite not taken, to misquote the poet.

In town, at lower speeds and riding through the scenery in the country, the Harley is more at home. The postures suit the speed and the normal body, the pace is relaxing and the handling is sure and predictable. Push the pace and the XLR’s drivetrain is working just right, in the sweet zone as the new isolation mounts live up to their promise, but the wide bars and wide pegs make headwinds a handicap. In the mountains, the same weight and width persuade the rider to leave a margin at every sparks-flying sweeper.

In town, the Thruxton rider sits up at every stoplight, lets go of the left grip and shifts in the saddle on the scenic route, and braces both feet when a passenger climbs aboard because those narrow clip-ons are leverage-free.

And then the road opens, the pace quickens and at 70-plus, the wind balances the crouch and the balance shifts to the comfort zone. On challenging roads at a sporting clip, the racing heritage comes into play. Look where you want to go and the Thruxton goes exactly there, a true sporting partner. And the conclusions, plural? We’re pretending here that the Harley-Davidson and Triumph families haven’t been competing, not to say feuding, for the past century.

If the choice will be made minus brand, if the pick is for the machine as it comes out the dealer’s door, the XLR has to win. It’s the quickest, the torquiest and it’s more suited to life as a daily rider.

If the buyer will make some changes, it’s much easier and more practical to swap the Triumph’s clip-ons for some oldstyle superbike-bend bars, add a flyscreen in the true Brit tradition, than it would be to subtract the Harley’s extra weight or tune the suspension for sport.

The safest bet, after all the weighing, timing and calculating, is that the Harley crowd will go for the XLR and the Triumph fans the Thruxton. That’s why the brands have been with us for the motorcycling equivalent of forever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

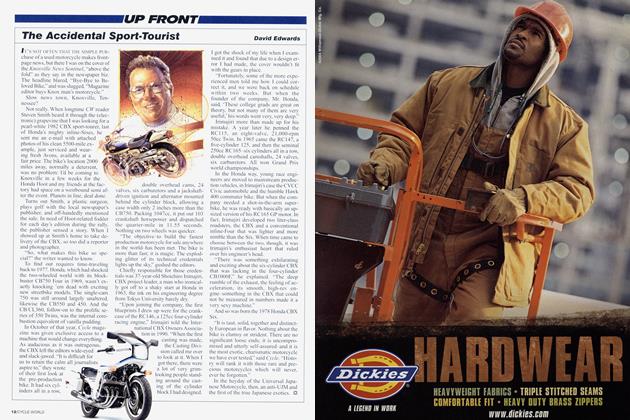

Up FrontThe Accidental Sport-Tourist

November 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKtm Unplugged

November 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBigger Big Bangs?

November 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2004 -

Roundup

Roundup2005 Bmw K1200s: Too Fast For the Autobahn?

November 2004 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Goes To Motogp

November 2004 By Bruno Deprato

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

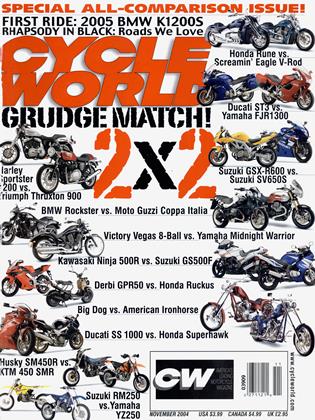

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!

-

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!

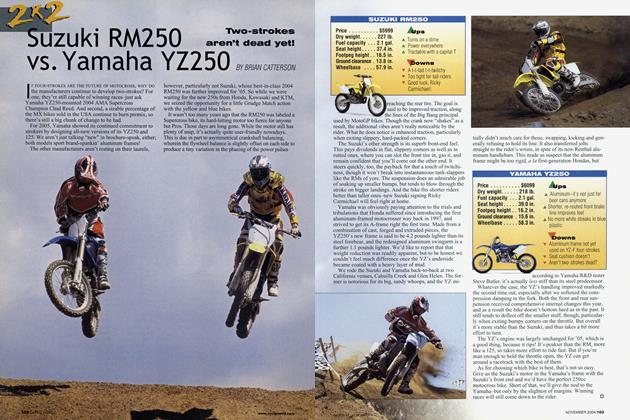

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!Suzuki Rm250 Vs. Yamaha Yz250

NOVEMBER 2004 By Brian Catterson -

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!

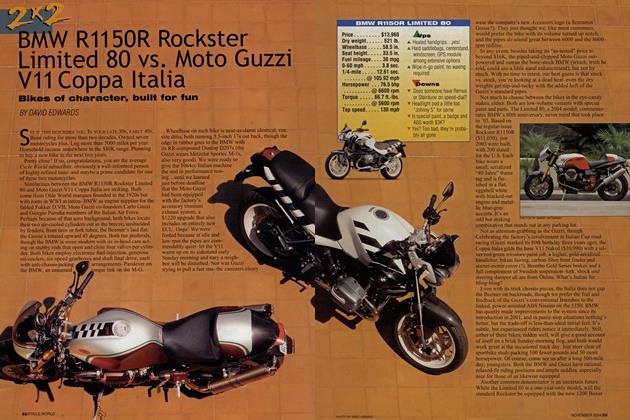

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!Bmw R1150r Rockster Limited 80 Vs. Moto Guzzi V11 Coppa Italia

NOVEMBER 2004 By David Edwards -

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!

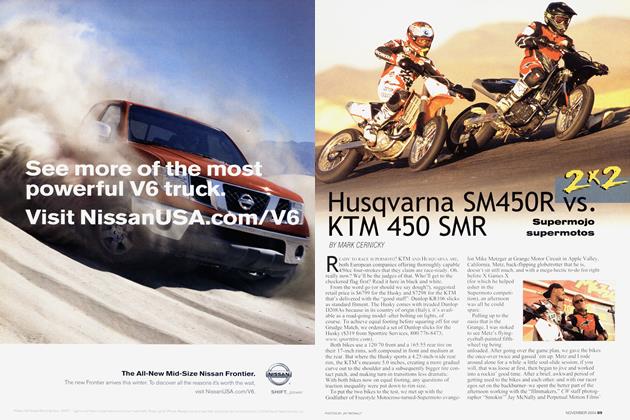

Special Section: 2x2 Grudge Match!Husqvarna Sm450r Vs. Ktm 450 Smr

NOVEMBER 2004 By Mark Cernicky