Cilpboard

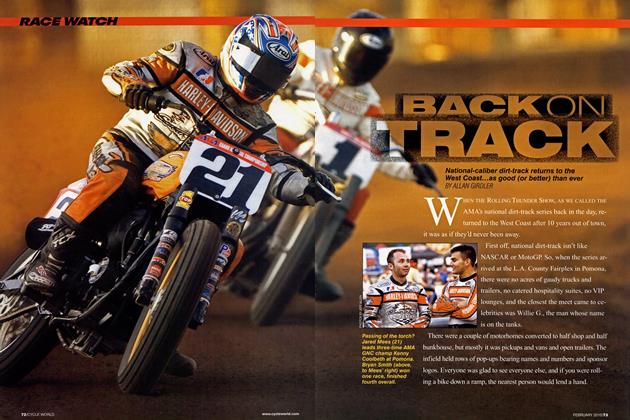

RACE WATCH

On the trail of the Hailwood Ducati

There was conflict, confusion and several different stories, but one man with a stack of cash has ended the controversy as to the whereabouts of the “real” Ducati that Mike Hailwood used to win the Isle of Man TT in 1978.

An investment banker named Michael Auriana simply bought out everybody who claimed they had a piece of the bike.

The series of events that led to Hailwood riding the bike began at Silverstone in August, 1977, when the aging nine-time world champion was wandering around the pits and spotted the Sports Motorcycles Ducati NCR 900 of Roger Nicholls. He swung a leg over it and commented that this was the kind of old-fashioned bike that he liked, and would enjoy at the Isle of Man. Within 10 minutes, Hailwood had committed himself to ride in the 1978 Formula One TT, and by the end of September the deal was signed with Sports Motorcycles’ team owner Steve

Wynne. Ducati agreed to provide special F-l machines and, atypically, two arrived in plenty of time.

The pair of NCR 900s that the team received at the beginning of 1978 were Hailwood’s machine, engine number

088238, and Nicholls’, engine number

088239. Hailwood did all the pre-TT and official practice through until the Friday evening with 088238, but for the final practice and race Wynne installed a new engine, 088243, that he had asked Ducati to ship in at the last minute.

“I paid for factory technicians Franco Farnè and Giuliano Pedretti to come over with another engine. They were worried the original engine had too many miles on it, so they replaced it. I think they may also have had some failures,” Wynne recalls. “This new engine had none of my mods, except a Lucas Rita electronic ignition. Everything else was standard NCR, including the gearbox.”

The new engine was no slouch. Hailwood won the F-l race at an average speed of 108.51 mph with a fastest lap at 110.62 mph. After the race, it was found that the bottom bevel gear had sheared as the bike crossed the finish line, so the original engine was re-installed for the following Mallory Park, Donington Park and Silverstone races. With this engine Hailwood won at Mallory, and set the fastest lap of 88.744 mph at Donington before crashing. He finished third at Silverstone.

What happened to the Hailwood Ducati has been a matter of conjecture ever since, exacerbated by the existence of two engines and the sister Nicholls machine. At the end of the 1978 season, Wynne sold the Hailwood bike, with the original engine, to a Mr. Hiyashi in Japan, while British Ducati distributors Coburn and Hughes retained Nicholls’ machine. They later sold it to Wolfgang Reiss in Hanover, Germany, with a certificate stating that it was the Hailwood bike (complete with a left-side gearshift conversion).

The spare engine that won the F-l TT was totally rebuilt by Wynne, who says, “It had a different crank, gearbox, 90mm pistons and the only parts left were the crankcases.” Wynne installed this engine in a later NCR chassis and> entered it in the 1981 Daytona Battle of the Twins race. There, the crankcases split, “most likely because I machined too much out to fit the big bore,” says Wynne. This engine was sold and eventually formed the basis of a complete NCR 900 identical to the Hailwood bike, also claiming to be the original. There were now three Hailwood Ducatis, but according to Wynne, “The race-winner was always the bike with engine 088238, even though that engine didn’t win the race.”

Finally, the story ends with American Auriana, an avid but quiet collector. Not only did he buy Hailwood’s race-winning bike for a reported $125,000, but he later purchased the Nicholls bike and the spare engine that won the Isle of Man TT. So the debate over who owns the real “real” Hailwood Ducati is over

at last.

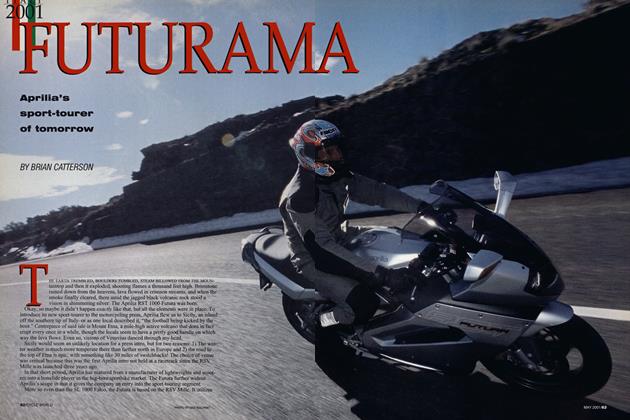

Ian Fallon

Colin gains confidence

Is there life after World Superbike for two-time champion Colin Edwards? If you read Feature Editor Mark Hoyer’s recent interview (“Never Give Up,” CW, January, 2003), you’re aware that the 28-year-old Texan was “rewarded” by Honda for his years of hard work by being offered a B-team MotoGP ride on Bridgestone tires. And that he’d turned that ride down in favor of a more lucrative position with the Aprilia MotoGP squad on his preferred Michelins. He’s ridden the high-tech, three-cylinder RS Cube a couple of times since then, so when we learned that he’d be signing autographs in the Aprilia booth at the nearby Long Beach Motorcycle Show, Managing Editor Matthew Miles and I seized the opportunity to check on his progress.

Two things you need to know about interviewing Colin Edwards: First, he doesn’t pull any punches, meaning he says what’s on his mind in whatever manner he thinks it at the time-apologies in advance for some of the more “colorful” comments that follow. And second, he could give a good interview all alone in a locked room; just turn on the tape recorder and let the quotes fly!

Even though he’d only tested the Aprilia twice by the time we talked in early December, Edwards had already done an about-face regarding his opinion of the bike-particularly the fly-bywire throttle, which he originally suspected caused his big crash the first time he rode it at Jerez, Spain, in November.

“It was only my fourth lap out there. I didn’t even know the track or anything,” he recalls. “I was simply trying to get a little feel and see what’s here and what’s there. It stepped out about an inch, and as I shut it down, it went another 4 or 5 inches. After that, it was all over. I didn’t need that, but I picked myself up off the ground. Got a little hole in my elbow, a little shiner.

“At the first test, I thought that I shut it down but it didn’t shut down-there was a delay or whatever,” he continues. “But now, it’s completely changed. I’ve gone from being a non-believer to a believer. There’s still a couple percent that we need to fine-tune-I’m so used to cables and having the friction everywhere. We put in a harder return spring to make it more resistant, and when I went back and tested it again, I was really, really happy with it. I never thought I’d say that, but the lap times showed it. We did 1:43s all day long on a race tire. (Valentino) Rossi did a 1:42.9 on a race tire.”

Naturally, we wondered about the difference between the Aprilia and the Honda RC51 Edwards was used to racing. >

“It’s really fast,” he said of the RS Cube more than once during our conversation, and offered an unusual description of the riding experience. “You find the biggest, meanest bull, chop off his balls, dangle them in front of him, then hop on his back. That should give you some reference point. Either that, or shove a shuttle rocket up your ass. Take your pick.

“It’s a bigger step than going from a 600 to a Superbike, that’s for sure,” he continues. “Grand Prix bikes are different, a lot lighter. The Aprilia doesn’t really compare to anything. It feels 10 times faster than the V-Five Honda did when I rode it a year and a half ago. The V-Five had a similar power curve to the V-Twin, just more of it. This thing’s power curve is quite a bit different. That’s one thing you have to get used to.”

There are, of course, plenty of other things, all of which need to be learned and understood before progress can be made.

“We figured things out relatively quickly,” Edwards explains. “We changed a lot of stuff. It wasn’t suited for me. I’m not sure who it was suited for, but it definitely wasn’t me. When I first got on it, I didn’t know the bike. Now, my confidence is like 98 percent.

I can actually go in and toss it on its side and if the front goes away, I feel like I can get it back. It’s not like going in there blind and hoping everything stays together.”

Part of the learning experience included seeing how quickly Aprilia was able to react to his requests.

“From the first test to this last test, it was only a week and a half or two weeks, yet things were just instantly done,” Edwards enthuses. “That’s one thing I’ll say about Aprilia: They’ve got a lot of Indians and only one or two chiefs. Honda’s the opposite: I’m so used to asking for something and asking for something... Sooner or later it comes, but it’s often later. Then, when you got it, it was like you opened a trunk full of gold. Whereas these guys at Aprilia are fast-forward.”

Throughout his career, Edwards has professed his desire to compete in the premier MotoGP class, but says he now has more to prove than his own abilities. And he’s got an unofficial “teammate” in former World Superbike rival Troy Bayliss, who will also be making his MotoGP debut this year on the Ducati Desmosedici.

“As often as Troy and I were fighting each other last year, now we’re kinda on the same team, if you can imagine that,” Edwards explains. “We’ll still be fighting one another, but at the same time, I want to see him succeed just as badly as I want to succeed for the simple reason that we’re four-stroke guys. We’ll be trying to prove that Superbike riders aren’t what some Grand Prix guys might think. We’re just as strong, just as tough and just as fast.”

And he’s put that whole Honda episode behind him.

“Now that I’m outside the Honda peripheral, I’m so relieved,” he says. “And it wasn’t just me. Everybody thought that when Honda signed Nicky (Hayden), I got shafted. But now I know it wasn’t just me; I was actually the third guy in line behind (Loris) Capirossi and (Alex) Barros. Those guys had been sitting there, hanging out for all these years, waiting to get on the factory bike. Maybe next year, maybe next year...and always getting the shaft. I didn’t realize that until I went to the last GP of the year at Valencia, Spain, and heard that Barros was going to Yamaha and Capirossi to Ducati. Wow!

“Now that I’m out of there, I’m so happy-happier than I’ve been in a long time. I’ve always been a happygo-lucky guy, but to be free, clear... I’ve actually got the factory working for me now.

“We’re winning races, man, don’t worry. Beyond a shadow of a doubt, we’re winning

Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

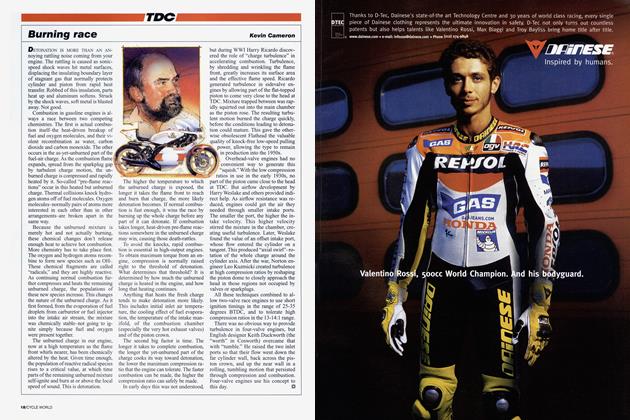

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

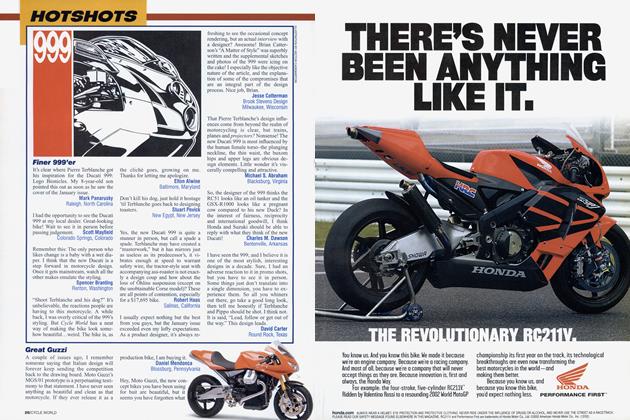

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

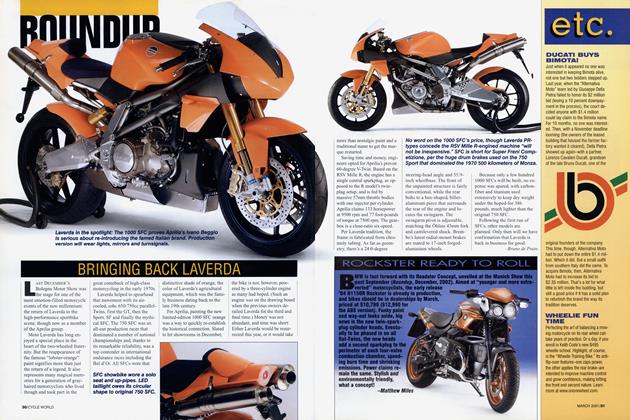

Roundup

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles