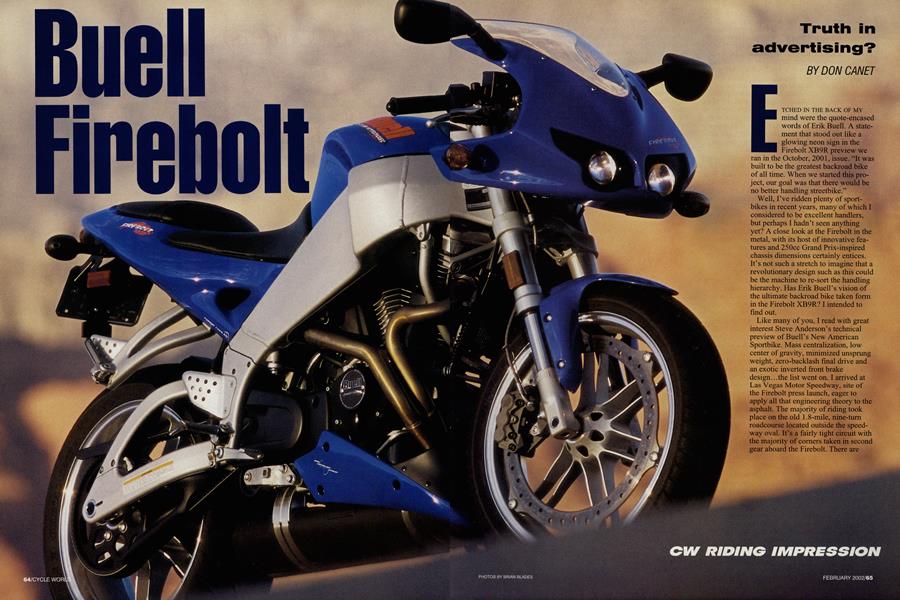

Buell Firebolt

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Truth in advertising?

DON CANET

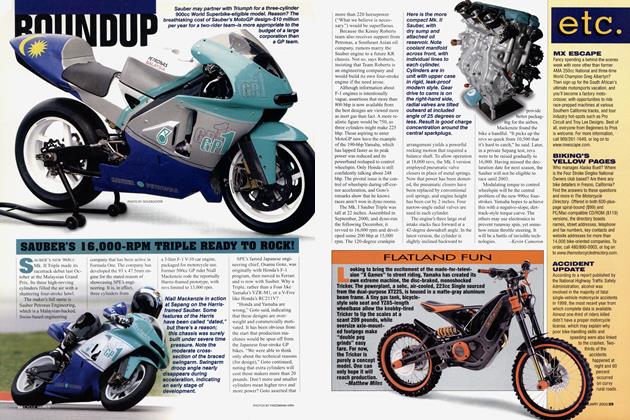

ETCHED IN THE BACK OF MY mind were the quote-encased words of Erik Buell. A statement that stood out like a glowing neon sign in the Firebolt XB9R preview we ran in the October, 2001, issue. “It was built to be the greatest backroad bike of all time. When we started this project, our goal was that there would be no better handling streetbike.”

Well, I’ve ridden plenty of sportbikes in recent years, many of which I considered to be excellent handlers, but perhaps I hadn’t seen anything yet? A close look at the Firebolt in the metal, with its host of innovative features and 250cc Grand Prix-inspired chassis dimensions certainly entices. It’s not such a stretch to imagine that a revolutionary design such as this could be the machine to re-sort the handling hierarchy. Has Erik Buell’s vision of the ultimate backroad bike taken form in the Firebolt XB9R? I intended to find out.

Like many of you, I read with great interest Steve Anderson’s technical preview of Buell’s New American Sportbike. Mass centralization, low center of gravity, minimized unsprung weight, zero-backlash final drive and an exotic inverted front brake design.. .the list went on. I arrived at Las Vegas Motor Speedway, site of the Firebolt press launch, eager to apply all that engineering theory to the asphalt. The majority of riding took place on the old 1.8-mile, nine-turn roadcourse located outside the speedway oval. It’s a fairly tight circuit with the majority of comers taken in second gear aboard the Firebolt. There are three hard braking zones, and a few curves that solicit deep trail-braking on entry. While the surface is fairly new, cars have already created pronounced braking ripples going into several comers, which put the Firebolt’s Showa suspension to the test. The back straight leads into a fast, sweeping right that rewards those with enough skill and courage to hold it pinned in top gear through the heart of the curve.

Leathered up and ready to rip, I climbed aboard my assigned bike and settled in. The overall package feels compact, more like a Ducati Supermono than any of its larger Buell brethren. The Firebolt’s 31-inch seat height allows firm footing at stops, and the riding position is surprisingly roomy. Long-legged riders will find plenty of space in the frame’s sculpted knee cutouts, and the forward lean to the bars isn’t excessive for even pintsized pilots.

Borrowing from the Blast, the Firebolt’s ignition switch incorporates a steering lock and uses a conventional key, a welcome move away from the Harley-style Coke machine key used on earlier Buells. Turning on the ignition sets the stepper-motordriven tach and speedometer needles into a diagnostic dance. The engine readily cranks over with a thumb of the starter button and quickly settles into a 1000-rpm idle, no fussing with a choke or high-idle lever, as the closed-loop fuel-injection computer handles all.

Throbbing power pulses at idle, a stiff clutch pull and the solid ker-thunk as you drop into gear are the only Sportster-ish traits that remain. The Firebolt’s “DoubleBlast” 984cc, air-cooled, 45-degree V-Twin combines a shorter stroke and significantly lightened rotating mass for a snappy, quick-revving nature the 1200cc Buells can’t match. Pulling away from a stop in low gear results in far less of the traditional Harley chug-a-lug-if that’s a trait you come to miss, simply load the engine in a tall gear and shudder yourself silly.

Engine vibes smooth considerably as the revs surpass 3000 rpm, leading to a well-placed sweet spot around 4000 rpm that equates to 70 mph in top gear. So effective at vibration isolation is Buell’s Uniplanar engine-mount system that very little buzz is felt through the aluminum clip-on handlebars even though no bar-end weights are used. Some vibration is felt through the cast-aluminum footrests, but these pegs are such a big step forward from the squishy, rubber-covered items of Harley heritage found on other Buells that you won’t care.

My immediate impression of the bike while learning the circuit wasn’t at all what Fd anticipated. Steering was a good bit heavier than I imagined 21 degrees of rake and 3.3 inches of trail would deliver; plus, the Firebolt had a slight tendency to right itself in comers. No sooner had I removed my helmet after the session than members of the Firebolt design-and-development team were asking what I thought. My observations regarding the less-than-neutral steering resulted in a host of suspension adjustments being made before my next stint. An increase of one step on the shock’s seven-position spring-preload adjuster combined with a 4mm reduction in fork preload and slowing the fork’s rebound, plus softening the compression damping netted slightly quicker steering response.

Things felt much better early in the second session. I now knew where I wanted to be on the track and was able to think well ahead of the bike. What had seemed higheffort earlier-the basic operation of shifting, braking and turning-all began to flow with an increase in speed. Seemingly limitless cornering clearance (only the footpeg feelers scratching on occasion) and the ultra-short 52-inch wheelbase made holding a tight arc through the track’s pair of double-apex comers an almost magical experience. The harder I rode, the more admiration I developed for Buell’s achievement as the bike became a transparent, sharp-edged, comer-carving tool beneath me.

Evidence of low unsprung mass was apparent as I tapped the limits of adhesion provided by the standardfitment Dunlop D207 Sportmax street radiais without a trace of tire chatter. Another revelation was the bike’s solid high-speed stability. I half expected a bike with such aggressive chassis dimensions would require a steering damper, but the Firebolt neither has nor seems to need one. I did detect the slightest bit of bar shimmy at a range of speeds-something that may possibly become more pronounced with tire wear-but didn’t see a hint of serious headshake at any time.

Buell’s technicians further adjusted my bike’s suspension, but never fully eliminated the XB9R’s minor tendency to stand up in comers. While this really didn’t present a problem, I would expect more in the way of neutral steering from the world’s best-handling streetbike. Makes me wonder if too low a center of gravity is responsible. Thinking back to my childhood playthings, Weebles wobble but they don't fall down. They do right themselves, however. Suspension compliance over bumps is superb to the point I was soon requesting firmer settings to increase the amount of feedback from the tarmac. The fork didn't bottom even when braking hard enough over the Turn 1 ripples to float the rear wheel in the air. While such braking antics were possible, I found a need for more stopping power from the front binder during hard-charging track sessions. Plumbed with a braided-steel line, the five-position adjustable lever retained a firm feel, but an equally firm three-finger squeeze was required to maximize slowing from higher speeds. I inquired about choice of pad com pound used in the Nissin six-piston caliper, and was told the selected pads offered the best balance of performance and extended rotor life.

I should say that my impression of this same brake setup on the following day's brief street ride was quite favorable. It's not too grabby, very progressive and offered ample stopping power in real-world situations.

What about power delivery and acceleration, those other all-important aspects of the ultimate backroad weapon? Simply put, the Firebolt's best hope to hang with a current 600cc inline-Four between two well-spaced corners relies on the rider's ability to exploit the `Bolt's early on-throttle capa bility. Torque-rich and extremely tractable, the powerband forced me to reprogram my perception of how early after a corner's apex I could apply big power to maximize drive out. None of this would be possible but for the glitchless response and smoothness provided by the XB's fuel-injection.

Another element any rider will appreciateis the broad, flat spread of torque. Many corners offered a choice of two gears that produced similar exit speeds. I found short-shift ing at 6000 rpm yielded pretty much the same acceleration as revving to the engine's 7500-rpm redline.

Aside -from the overly stiff clutch, I have no complaints in the engine depart ment. Shifting action sets a new standard for Buell products,

as does the tight feel of the drivetrain. Overall fit and finish is of high quality, topping all existing efforts we've seen to date from America's leading (only) sportbike manufacturer. While it's safe to say the Firebolt is the best-handling Buell ever, is it the greatest backroad bike of all time? The quick answer is maybe. The long answer in due time-a heads-up comparison is in the making.