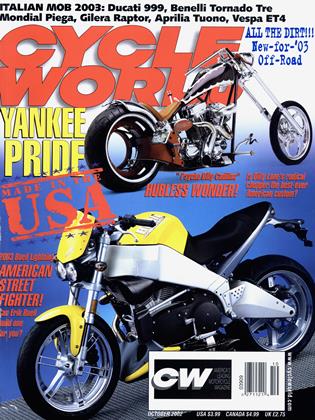

Buell XB9S

Proof that Lightning does strike twice

STEVE ANDERSON

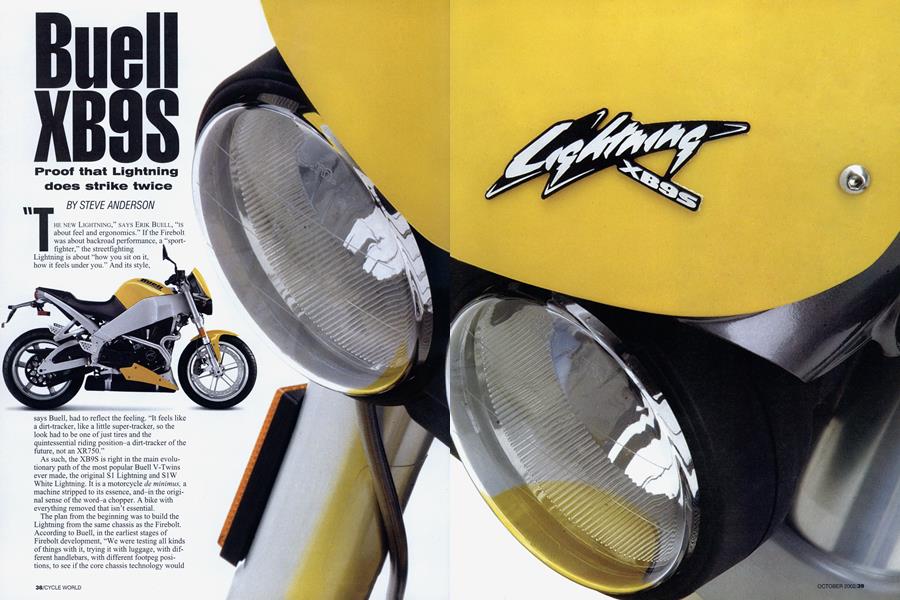

“THE NEW LIGHTNING,” SAYS ERIK BUELL, “IS about feel and ergonomics.” If the Firebolt was about backroad performance, a “sport-fighter,” the streetfighting Lightning is about “how you sit on it, how it feels under you.” And its style, says Buell, had to reflect the feeling. “It feels like a dirt-tracker, like a little super-tracker, so the look had to be one of just tires and the quintessential riding position-a dirt-tracker of the future, not an XR750.”

As such, the XB9S is right in the main evolutionary path of the most popular Buell V-Twins ever made, the original SI Lightning and S1W White Lightning. It is a motorcycle de minimus, a machine stripped to its essence, and-in the original sense of the word-a chopper. A bike with everything removed that isn’t essential.

The plan from the beginning was to build the Lightning from the same chassis as the Firebolt. According to Buell, in the earliest stages of Firebolt development, “We were testing all kinds of things with it, trying it with luggage, with different handlebars, with different footpeg positions, to see if the core chassis technology would work with different motorcycles.” Buell engineers quickly learned that not only would it work, but that it would work very well indeed.

So the basis for the new Lightning is the Firebolt. The main frame and 984cc engine are identical, as are wheels, suspension and brakes-almost everything that determines performance. The new machine carries the same tiny 52-inch wheelbase, the same steep 21-degree steering geometry, the same radical solutions to tight packaging-fuel in the frame, oil in the swingarm and a big, inside-out, single-rotor front brake. What is most different is the riding position. Footpegs are an inch lower (and easily retrofitable to the Firebolt), and a for-real tubular handlebar is clamped to a new top triple-clamp. The 28-inch-wide bar rises just enough to put the rider in a slight forward lean, with the handgrips almost perfectly located for a natural riding position. Sit on the XB9S, and it feels like a dirtbike. A low dirtbike.

“Developing the riding position was straightforward,” says Buell. “After that, all the work went into the development of the look, and the packaging-making everything super-compact and capable of fitting into the tiny tail and nose.” Where the Firebolt nose reaches out, the Lightning nose is snub. “I took a printout of the basic chassis and put a numberplate on it,” says Buell, “and then I said, ‘That’s what I want it to look like.’ The designers told me you couldn’t get a headlight in there, so I asked, ‘How close can you get?”’

Pretty damn close was the final answer. The Lighting’s headlights are supplied by Italian company Triom, selected because it was willing to work hard to achieve the desired result, which required more than off-the-shelf hardware. The twin lights, designed specifically for Buell, are pulled tight against the bottom triple-clamp, and rely on high-temperature plastics and the “chimney” cooling effect to live, rather than the luxury of broad spacing. They’re carried and surrounded by a multi-purpose aluminum box. The box mounts the ignition switch/fork lock on its left side, the numberplate/flyscreen on its front, and hides the hom and electrical components inside. The flyscreen is a particularly nice styling touch, picking up the instrument bulge of the original SI, while the shield-shaped bottom recalls the slanted eyebrows and aggressive face of the Firebolt.

Without an ignition switch on top of the triple-clamp, the very light integrated tach/speedo/odometer package from the Firebolt, fitted with new graphics, can nestle into the small space behind the flyscreen. The overall effect is extremely clean, with the fuses and relays seen alongside the fairing mount of the 9R relocated under the seat. Indeed, when you sit on the Lightning, you have to consciously look down to see any of the motorcycle at all - the front tire, the flyscreen, the instruments, none of that is in your field of view with a helmet on.

The rear of the Lightning is as chopped as the front. Buell said he instructed the design team that he didn’t want the new Lightning “to have any tail. I wanted this bike to be more SI than the S1.” Why? Buell and others had realized that the 1999 XI Lightning wasn’t “as much on edge” as the original SI. The reasons for that were simple. Before designing the XI, Buell surveyed essentially every motorcyclist who test rode an SI and didn’t buy it, and set out to answer their-and motorcycle magazines’-complaints. But in doing so, Buell was essentially designing a motorcycle for the people who didn’t want an S1, a machine that was already selling well and that had an incredibly strong image. It’s little surprise, then, that the XI came out less radical, smoother appearing, heavier and in many ways more conservative than the S1 it replaced.

With the XB9S, the radicalism has returned, but with far more attention paid to build-quality, styling and ergonomics. The stubby-looking seat isn’t the butt wedge the S1 seat was; instead, it only starts narrow then widens to almost 12 inches. That should offer enough surface area to prevent butt-bum. The “gas tank” (actually the airbox) of the 9S is shorter than the tank of either the X1 or the S1, so that even though the seat looks stubbier, there is actually more room for the rider. Most of the compact look results from a new, aluminum subframe that wraps around the rear of the passenger seat and no farther. Only a small aluminum appendage reaches back to carry the license plate and its light in their legally mandated positions. Essentially and visually, this motorcycle stops at the rear axle.

Customizers will have a field day. The subframe is made of three high-pressure vacuum-diecast pieces-two side rails and a rear section carrying the taillight and the license-plate extension. With their fine surface finish, they can be polished with ease, and likely the aftermarket will offer alternative, shorter plate carriers. Change that, unbolt the various reflectors and the passenger-peg brackets, and you’ll have created a machine that can no longer accommodate a passenger but will shine with the bmtal simplicity of a dirt-track racer.

Still, Buell sought to separate bmtal appearance from bmtal behavior. The Lightning uses the same fuel-injected engine that provides exceptionally smooth power delivery for the Firebolt. The mbber engine-mounting system is the same, and should offer a similarly high level of vibration control. Design detailing is especially neat, from the easy to reach and use ignition switch to the uniquely tidy packaging of wiring harness and electrical components under the seat. And reliability is a bugaboo that Buell hopes to have put long behind it with both the Firebolt and the Lightning.

Ever since the Blast, Buell has concenj trated on designing in quality from the beginning, and its larger production volumes and close ties with Harley have allowed it to carefully choose world-class suppliers who can deliver absolute, repetitive consistency in components-something sorely missing in the early days of the S2. Both the XB9S and 9R were subjected in both prototype and production forms to Buell’s new “accelerated European endurance test,” a 10,000-mile demolition derby that models how the most bezerko of Euro riders with an autobahn handy might choose to use one of the bikes. It includes a mix of continual full-throttle acceleration through the gears, long sustained top-speed mns, maximum brake applications and general, all-’round abusiveness. That test, Buell’s own warranty statistics and outside surveys of quality have convinced Erik Buell that the current lineup of machines from East Troy can match or surpass the quality and reliability of any other motorcycles in the world, including those of the Japanese. Now he just has to wait for memories to catch up to the new reality.

In the meantime, Buell and his colleagues have crafted a Lightning with the same wonderful chassis, suspension and engine as the Firebolt. It’s a bike that offers a comfortable and control-focused riding position that just dares you to toss the 9S sideways the first time the road surface gets loose, a bike that carries such in-your-face styling that it makes other streetfighters look tame. And, if Erik Buell is right, the Lightning is a machine that points to a bright future for American sportbikes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontI, Ducatista

October 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Tale of Two Suzukis

October 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCY-Alloy? Why Not?

October 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupCruising In Luxury: Bmw R1200cl

October 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupCentennial Harleys

October 2002 By Matthew Miles