UNSQUARE FOURS

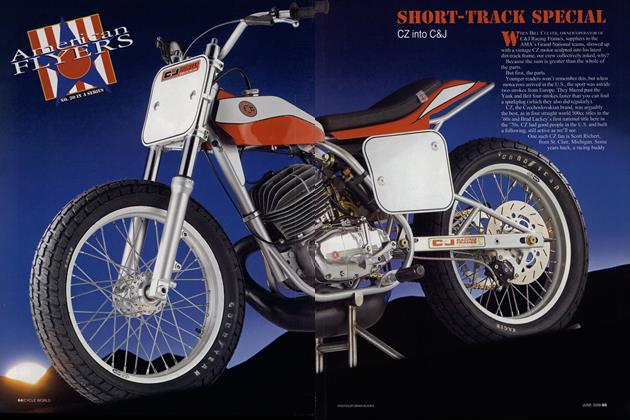

American FLYERS

Old School “Squariels”

FIRST IMPRESSIONS ARE important. Homer Knapp, owner of these two Ariels, arrived at the CW photo studio with the periodpiece customs lashed into the bed of a well-faded 1959 Ford Ranchero, held tight with lovely mil-spec tiedowns that may or may not have been lifted from the cargo deck of a C-124 Globemaster bound for the Korean War. The man knows how to make an entrance.

A skilled machinist, Knapp, 64, has fettled Jay

Leno’s myriad of collectibles and helped with the fabrication of Superbikes for HRC, Honda’s racing arm. These days you’re likely to find him behind the handlebars of one of these Ariels, fixtures on Southern California vintage rides and rallies. He’s owned the duo since 1996, purchased from the estate of the original owner, Arnold Bimer, pattern-maker and foundry worker by trade, “Bonneville guy” by avocation.

Characteristic of 1950s “California bobbers,” the first bike started life as a 1939 model, but was fitted with a ’47 telescopic fork, chrome plate shining brightly in place of the usual dowdy British black paint. Out back, there’s the bobbed fender typical of the breed, replete

with the requisite “limp dick” aftermarket taillight. Apparently tired of barking his shins on the elaborate Brooklands-style mufflers, Bimer took hacksaw to fishtails and shortened the offending metalwork, at the same time angling the cans inward for better cornering clearance.

While Knapp the historian is adamant about leaving the bike’s cosmetics in their scruffy, as-ridden state, Knapp the machinist couldn’t help but make unseen improvements to the engine and gearbox. “There are Orings and seals all over now,” he says

of the bob-job’s newfound oil-tightness.

About that engine: At a time when pushrod Singles were de rigueur in Europe and we were still happily plodding about on sidevalve V-Twins, Ariel designer Edward Turner (yes, later of Triumph Speed Twin fame) unleashed his 500cc Four for 1931, its cylinders arranged in a square configuration. Twin, gearedtogether crankshafts spun in the cases; valves were activated by another oddity for the day, an overhead camshaft. The design would grow to 600cc, then be thor-

oughly revised in 1937, becoming a 1000 with pushrod-operated valves. “Whispering Wildfire,” claimed the ads, “The Monarch of the Multis.”

For the time, the 1000’s performance was impressive. “There was no need to scrabble for gears, for from as low

as 10 mph in top gear the Four would pull away smoothly and rapidly without snatch. Acceleration using the gears was rapid,” notes marque historian Roy Bacon.

In fact, the powerplant easily outclassed its running gear, especially the wearprone plunger-and-link rear suspension. Bimer’s fix was to acquire the best-handling frame of the era, Norton’s legendary Featherbed. As seen here, the compact 995cc square-Four slotted easily into an engine bay originally intended for a 500 Single.

Bimer hot-rodded the motor with Ford V-Eight 60 pistons (see “Handy Hog,” page 50), although a little problem with dome clear-

ance brought the project to a halt. “Life got in the way,” says Knapp, and the Featherbed Four was pushed under a workbench. “That was the end of it.”

At least for the next three decades. In Knapp’s possession, the pistons have been reworked. Plus, oil supply is now routed through a Corvair oil-cooler mounted under the headlight, putting an end to pesky rear-cylinder overheating.

“It runs so good, I don’t really like to ride anything else,” Knapp says. “At 70 mph, it mns down the freeway at half-throttle, smooth as glass.”

Somewhere, Arnold Bimer is a happy man.

David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

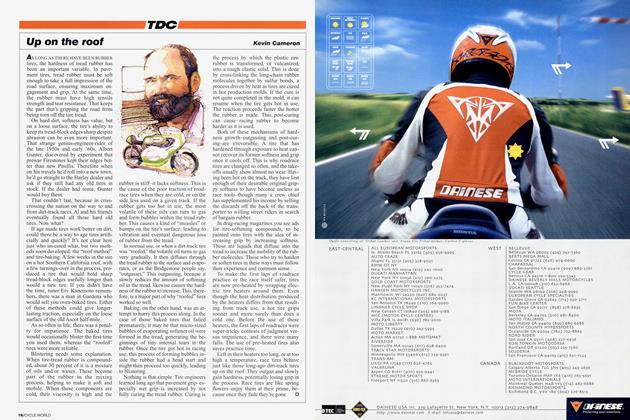

TDC

TDCUp On the Roof

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles