SERVICE

Paul Dean

Screeching to a halt

My 2001 Harley-Davidson Sportster is really an attention-getter. When I ride it through town, people stop and stare-but not because of its classic styling, highquality chrome or readily identifiable exhaust sound. Instead, they’re trying to figure out where that awful, grating, screeching sound is coming from. Seems Harley redesigned its disc brakes for the 2000 model year so that this annoying noise now is standard equipment. Three visits to the dealer and calls to the factory confirm that this noise is what I should expect, and that nothing can be done about it. There is a replacement pad available, but the dealers don’t know if it will help. The noise started at around 1000 miles and now, at 7000, is just as loud as ever. It would seem that a company that prides itself on producing classic designs and marketing continual upgrades would try to improve the product rather than taking incremental steps backward. Got any ideas?

Jay Miller Walnut Creek, California

Brake squeal is not limited exclusively to late-model Harley-Davidsons ; many other motorcycles-and even some automobiles-suffer the same kinds of brakenoise problems. And not all Harleys are guilty. I’ve only heard the brakes squeal on a couple of 2000/2001 Harleys I’ve encountered out on the road, and not one of our H-D testbikes over the past two years has exhibited such a problem.

Usually, the squeal is caused by a glaze that has formed on the rotor, the pads or both. The glaze changes the friction characteristics between the pads and rotor, causing the pads to vibrate at high frequency during certain braking conditions. If the squeal occurs when you ’re not even using the brakes, the culprit often is an accumulation of road grime and brake dust around the seals for the caliper pistons, which prevents the pistons from fully retracting.

First try the cheap route. Remove the caliper and take out the pads, then thoroughly clean the area around the pistons and seals with a commercially available spray brake cleaner. Scuff up the surface of the pads and the swept area of the rotor with a piece of emery cloth or a Scotchbrite pad, but don’t use brake cleaner to clean the rotor; some of those sprays leave behind a thin film that can lead to glazing of the rotor. Instead, clean the rotor with acetone and a clean rag.

If that doesn’t work, try new brake pads. Your Sporty ’s stock pads are the sintered-metal variety, which provide good bite on the rotor, but their very high metallic content often exacerbates squealing problems. That’s why swapping your existing pads for stock replacements may cure the squeal, but probably not for long. Several aftermarket brake firms make sintered-metal replacement pads for H-D brakes, and each company uses a slightly different formula for brewing up its sintered material; perhaps one of those would put an end to the squeal.

Another alternative is to use some of the organic replacement pads available in the aftermarket. They would very likely stop the squeal, but would sacrifice a bit of the braking power offered by the stock sintered-metal pads; plus, the organics would require more-frequent replacement. If nothing else works and the aforementioned compromises are acceptable to you, a switch to organic pads may offer the easiest fix.

Jenny Craig’s race team

I have a question about weight. Is it better for handling and general riding to save 10 pounds in bike weight or 10 pounds in rider weight? I realize the benefits of reducing unsprung weight but am not sure of the difference between a fixed weight on the bike (e.g., a muffler) and a moving part (the rider). In other words, should the money for that trick titanium muffler actually go toward a health-club membership? David Hamley Lakeville, Minnesota

If the rider’s nickname is “Tiny” or has the word “Big” in it anywhere, chances are quite good that a health-club membership is his best bet.

If you 're talking about a bike s acceleration potential, it really doesn’t matter where the weight loss takes place; whether the 10-pound reduction is in the pipe or the rider, the engine will end up with exactly the same amount of weight to pull, and the improvement in acceleration will be the same, as well. But if you ’re referring to a motorcycle ’s cornering capabilities, the location of the lost weight indeed does matter. The bulk of a rider’s mass is located above the combined center of gravity of the bike and rider, while most of an exhaust system s mass is either below it or-as on some current sportbikes that have mufflers tucked under the seat-at about the same level. Thus, a 10pound reduction in rider weight will usually lower the center of gravity more than an equivalent reduction in the exhaust system. Generally speaking, a lower center of gravity permits faster cornering speeds at any given lean angle, and improves the bike ’s flickability.

This principle is evident in the “mass centralization ” employed by most bike manufacturers in the design of their hot sport models. The closer a bike ’s masses are located relative to its center of gravity, the more quickly it is able to respond to the rider ’s steering inputs.

Threading the needle

I’m having a problem with my ’86 Yamaha 700 Fazer. I installed an ’87 FZR1000 engine in it and had the carbs tuned so it ran very well-until a friend took it for a little friendly backroad competition and missed a second-gear shift, causing it to hit the rev-limiter. After that, the engine would barely run below 5000 rpm, at which point it would take off and run normally. After much troubleshooting, I found that all the carb needles had gotten pushed up into the slides. I put all the needles back in place and the bike ran great again until another high-speed run (no overrev involved this time), after which the same thing happened again. The bike has been to a reputable shop, the compression is within spec for that year’s FZR engine and the carbs are synched. All the shop could tell me is that the No. 3 carb slide is hanging up slightly. Help! Any ideas? Fazermike Posted on America Online

Your Yamaha’s condition has nothing to do with missed shifts, carb synchronization, overrevving or compression values. The problem is that the needles are being pulled completely out of their respective needle jets when the vacuum-controlled slides reach their fully open position. The FZR has semi-downdraft carbs in which the slides move horizontally rather than vertically, so once the needles leave the needle jets, gravity causes them to drop just enough to no longer align with the jets. When the slides close, the needles bottom out on the venturi bores instead of slipping back into the needle jets, and they subsequently get hung up there while the slides return to the closed position.

Normally, malfunctions of this sort cannot happen. The slides are designed so their full travel is not sufficient to permit the needles to escape the needle jets. Furthermore, the retainers that hold the needles in place are designed to prevent them from getting pushed up into the slides just in case they do somehow slip out of the needle jets. But in an attempt to riehen the mixture, someone apparently has either installed needles that are too short or raised the stock needles too far by modifying their retainers. In either case, the effective length of the needles now is too short to keep them contained in the needle jets when the slides are fully open, and the retaining hardware either is improperly installed or missing altogether, allowing the needles to get pushed up in the slides.

You need to have a competent mechanic disassemble the tops of the carbs and closely examine the needles and their retaining hardware to determine what has gone wrong or is assembled improperly. Don 't go back to the people who told you one of the slides was hanging up; they don’t know what they re doing. Likewise, avoid the mechanic who “tuned” your carbs; he ’s probably the guy who screwed them up in the first place.

The numbers game

I own an aftermarket Harley clone with an 88-cubic-inch S&S motor. I’ve noticed that just about every bike you test makes more horsepower than torque. My bike does the opposite. It makes 20 more foot-pounds of torque than horsepower. Is that unusual or does it mean that my bike is not getting the horsepower that it should? Scotty Boy Posted on www.cycleworld.com

What it means is that you don 't understand what horsepower is or how it is measured. And there is insufficient space available here to explain those concepts in much detail. But in short, torque is a force that tends to cause rotation, and horsepower is a measure of the work that force performs over a period of time. Horsepower, in other words, is a mathematical computation. And it is calculated simply by multiplying the torque output by the rpm at which that torque is generated, then dividing by a constant, which is 5252. (Never mind how that constant is decided; it’s one of the things I don’t have room to explain.)

Simple math dictates, then, that at all rpm below 5252, any amount of torque output-no matter how big or small-will always result in a horsepower number > that is smaller than the torque number; conversely, at all rpm above 5252, any amount of torque output will always result in a horsepower number that is greater than the torque number; and at precisely 5252 rpm, the horsepower and torque figures for any engine of any kind will always be identical.

Even when heavily modified, HarleyDavidson Big Twins are comparatively low-rpm engines that almost invariably reach their torque peak well below 5252 rpm. As a result, their peak torque numbers are greater than their peak horsepower numbers, often by a considerable measure. An even more extreme example can be found in diesel truck engines, some of which make more than 1200 foot-pounds of torque at around 1500 rpm, but only about 400 horsepower at 2000 rpm or less.

Four-cylinder sportbikes, on the other hand, have high-revving engines that almost always make their peak torque above 5252 rpm. This means their peak horsepower figures are much higher than their peak torque figures. The torque peak of a Yamaha YZF-R6, for instance, is only 42 foot-pounds, but it occurs at 9500 rpm, and the engine makes 95 peak horsepower at 12,800 rpm. It’s all in the math.

Looking for Mr. Goodtune

I recently purchased a ’96 Kawasaki ZX6R that had 43,000 miles on it. The previous owner had modified it pretty extensively with an aftermarket exhaust, new jetting, an ignition advancer, suspension upgrades and the like. I’ve done a lot of maintenance on the bike since I bought it, including ensuring that the valves are all within spec, but the engine has an annoying problem: It stutters at about 70008000 rpm. In the lower gears it is less noticeable, but in fourth through sixth it is quite obvious. The engine acts as if it simply does not like this speed. It idles fine, and above 8000 rpm, it takes off like it’s supercharged. My shop recommends racing fuel to clear up the problem, but I have my doubts. Please help! Mark D. Boyce Posted on www.cydeworld.com

Your dilemma is a classic illustration of the problems associated with modified engines. Once you make changes that affect an engine ’s state of tune, they require you-or anyone who works on the bike-to stop being a conventional mechanic and start being a race tuner. And there is a huge difference between the two.

It ’s one thing to diagnose a problem on a stock motorcycle; but when you install a collection of parts that, individually, might be well-designed but were never specifically engineered to work with one another, you 're opening a can of worms, and it takes a very special set of skills to get it closed again. There are no shop manuals for such motorcycles, no diagnostic guides or service histories or tech bulletins. And unless you just happen to find a mechanic who has previously dealt with that exact combination of aftermarket pieces, there ’s no one with immediate answers at the other end of a phone line or e-mail. Figuring out the cause of the problem usually requires a logical, hands-on diagnostic procedure carried out by someone who really understands the effect each tuning component has on the performance of an engine.

It’s my wild guess that the problem with your Kawasaki is related to the exhaust system, the ignition advancer or both. If the exhaust, in and of itself, causes a small fiat spot at 7000 to 8000 rpm, and the ignition curve has been altered so that it is less than optimum for that rpm range, that small flat spot can easily become a big one. My suggestion is to remove the ignition advancer to see if the problem gets any better. If that fails, try’ to find a competent race tuner in your area and have him troubleshoot the problem. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find reasonable solutions in your area? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail your inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com and click on the Feedback button. Please, always include your name, city and state of residence. Don’t write a 10page essay, but do include enough information about the problem to permit a rational diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we can’t guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

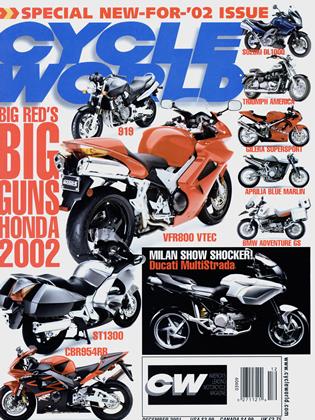

Up Front

Up FrontWind Machine

December 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Ducks

December 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAnyone Can Do It

December 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

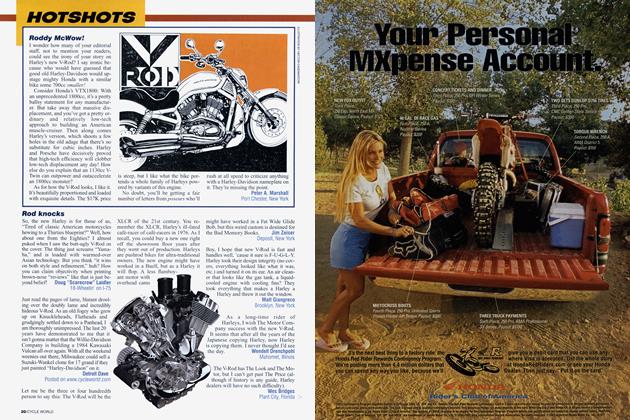

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupMerger Mayhem In Japan

December 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupIs Saddleback Back?

December 2001 By Brian Catterson