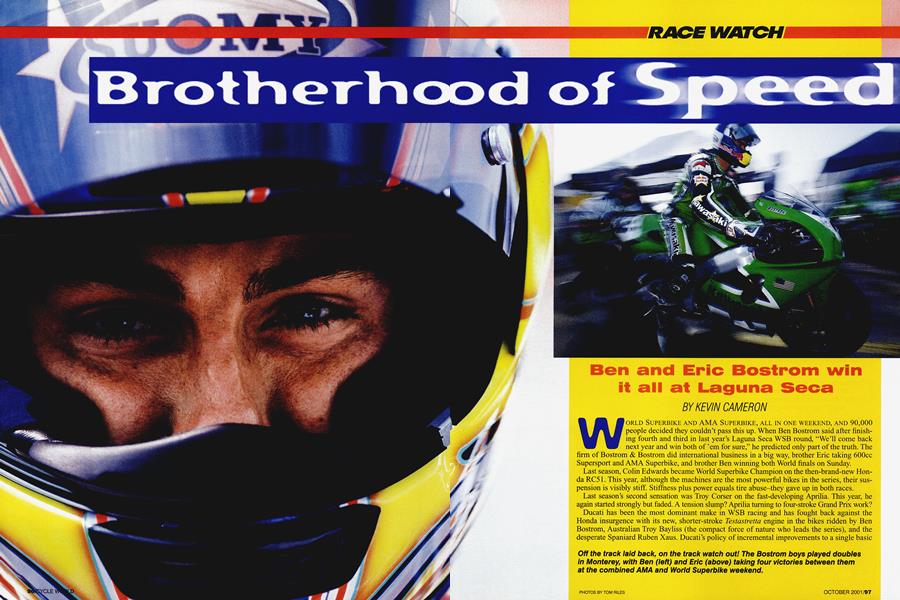

Brotherhood of Speed

RACE WATCH

Ben and Eric Bostrom win it all at Laguna Seca

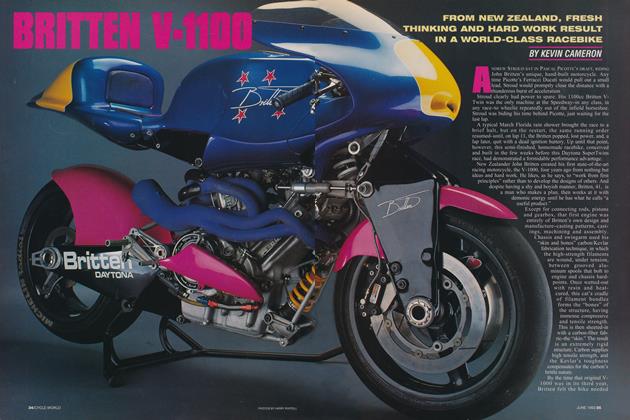

KEVIN CAMERON

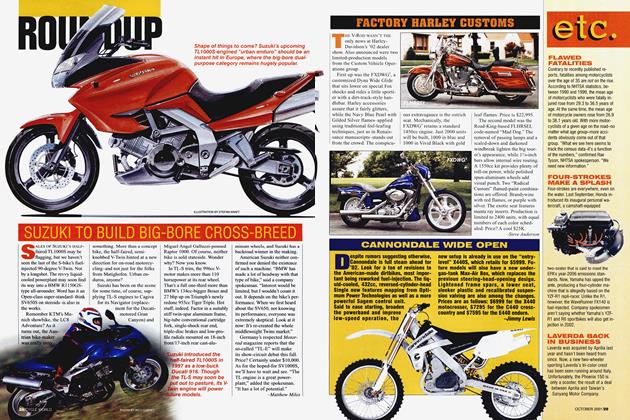

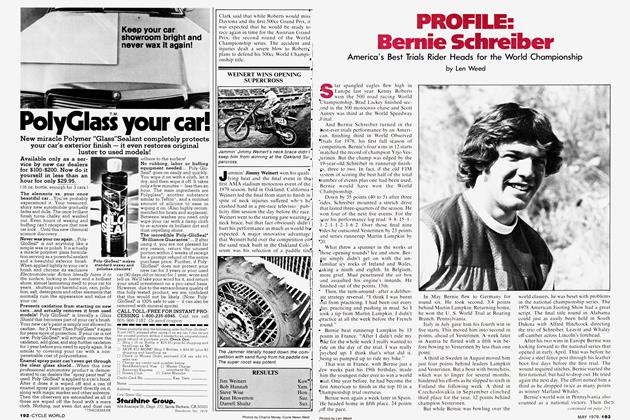

WORLD SUPERBIKE AND AMA SUPERBIKE, ALL IN ONE WEEKEND, AND 90,000 people decided they couldn’t pass this up. When Ben Bostrom said after finishing fourth and third in last year’s Laguna Seca WSB round, “We’ll come back next year and win both of ’em for sure,” he predicted only part of the truth. The firm of Bostrom & Bostrom did international business in a big way, brother Eric taking 600cc Supersport and AMA Superbike, and brother Ben winning both World finals on Sunday.

Last season, Colin Edwards became World Superbike Champion on the then-brand-new Honda RC51. This year, although the machines are the most powerful bikes in the series, their suspension is visibly stiff. Stiffness plus power equals tire abuse-they gave up in both races.

Last season’s second sensation was Troy Corser on the fast-developing Aprilia. This year, he again started strongly but faded. A tension slump? Aprilia turning to four-stroke Grand Prix work?

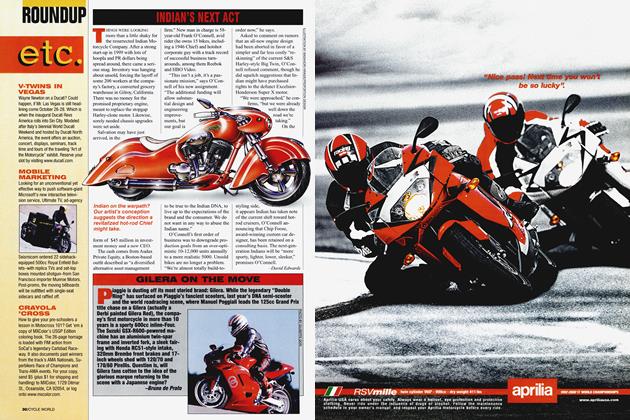

Ducati has been the most dominant make in WSB racing and has fought back against the Honda insurgence with its new, shorter-stroke Testastretta engine in the bikes ridden by Ben Bostrom, Australian Troy Bayliss (the compact force of nature who leads the series), and the desperate Spaniard Ruben Xaus. Ducati’s policy of incremental improvements to a single basic design continues to produce the best all-around package. The orange GSE Racing Ducati 996RS bikes of Neil Hodgson and James Toseland are last year’s machines, yet the likable Hodgson scored a second and a third on Sunday. This is strength in depth.

The sound of World Superbike is the sound of Twins-Ducati, Honda and Aprilia. Italy’s evergreen superman PierFrancesco Chili scores occasionally on his inline-Four Alstare Suzuki GSXR750, but isn’t a title contender. People suggest poor communication between Alstare and the home office, plus the fact that two crucial technicians-for fuel injection and suspension-have been withdrawn to Japan. Chili qualified eighth, was knocked down in Race One, and retired disgusted from Race Two with gearbox problems. The Fuchs Kawasaki team, run from Germany by former rider Harald Eckl, fields Akira Yanagawa and Gregorio Lavilla. They ride to uppermiddle finishes against private Ducati teams. Looking terribly employable on his supposedly underpowered AMA series Kawasaki ZX-7R was Eric Bostrom, with two fifths against the World field.

Benelli’s 900cc Triple is the presen! novelty, ridden by development specialist Peter Goddard. This inline engine has a 120-degree crank, giving even-fire 240-degree impulses. Its unique sound is like that of a big outboard motor, muted, powerful and also musical. If qualified 1.7 seconds off pole and finished 18th and 15th. Cooling is by & Britten-style under-seat radiator, ramfed air from a pair of ducts. Everyone is glad Benelli is back in racing.

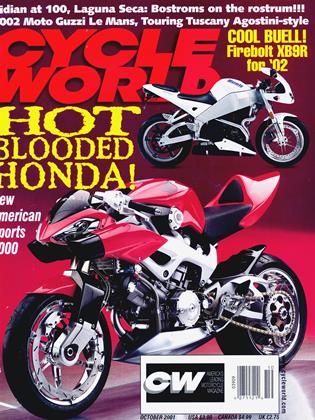

The Aprilia 60-degree V-Twins of Corser and Regis Laconi have new oil tanks mounted low at the left side of the crankcase, moved from under the seat. As in fighter aircraft, space is scarce on bikes. Aprilia enlarged its airbox last year and might like to again, making it hard to find room for chassis beams, airbox, gas and oil together in a compact package. I expect to see fuel or oil in chassis beams soon (see the new Buell Firebolt, for example).

Ducati’s new fairings have smooth sides-no exit slots for hot radiator air. This cut the old Supermono racing Single’s drag, so it was adopted for the 996R. Exit air now emerges from within the top edges of the fairing, under the rider’s forearms. We can’t see jets of hot air emerging from the fairing sides, but Mother Nature can!

The Castrol Hondas started this year with “electrical trouble”-engine blowups rumored to have resulted from bearing quality-control issues. Honda troubleshooters soon trampled this to death, but handling isn’t so easy to fix. Each power increase has forced the team to stiffen the rear suspension. We’d all love to see Edwards doing better than he is (second in the series standings, 53 points down), but engineers work hardest on things they can measure-like horsepower.

Laguna was once a suspension compromise; bikes had to be soft enough to eat the ripples that were everywhere, yet avoid bottoming at the exit of the Corkscrew. Next the ripples were flat-> tened in a pavement-improvement program. Now they’ve risen up again-dips off Turn 5, a hint of the former washboard downhill from the bridge in Turn 9, and my favorite “suspension tester” close to the first upshift off Turn 11.

When you watch Bayliss on the pressroom TV feed, his bike twitching and hammering like a motocrosser, and then you see this small man in person, you can hardly connect the two. His Infostrada 996R dances over bumps but never wallows-call it controlled movement.

Eric Bostrom is reborn. Stepping up from Supersport and Formula Xtreme in 1998 to a Honda RC45 V-Four Superbike, perhaps the world’s most difficult and idiosyncratic racing motorcycle, the younger Bostrom quickly mastered things and won two AMA nationals at the end of that season. In 1999, still on an RC45, his career fell flat. Then, last year, on the newly in-house Kawasaki team, he regrouped. This past spring at Daytona, he survived troubles all around him to finish a fine second place.

Then came the Atlanta test. His crew chief/engineer Al Ludington says Bostrom returned from practice saying, “There are two turns out there where this bike is perfect. That’s what I want-for the bike to be like that everywhere.”

This was crucial because few riders really know what will work for them. Others are seeking a mountain in fog-without direction. For Bostrom, the fog lifted to reveal the shining peak. In setup, everything builds on everything else. When things start to work, there’s a synergy of success. Bostrom had taken to the RC45 naturally, but his slump was > a retreat from nature-like suddenly being unable to dance without looking at your feet. The steps may be right, but every one is an effort.

Bostrom returned to his natural powers at Loudon this year, where he held off a relentless attack from AMA series leader Mat Mladin-and won. Ludington comments that when things are right, going fast is easy, the most natural thing. Trying harder doesn’t help, it hurts. Bostrom would also ride the WSB races on Sunday as a wildcard with teammate Doug Chandler. Yamaha’s Anthony Gobert was entered, but the broken wrist he sustained in his Loudon crash sidelined him from racing Superbikes-both AMA and World-at Laguna. He finished an admirable seventh in AMA 600cc Supersport, his team’s priority since he’s fighting for the championship lead with Bostrom in that class.

Engineers are another Laguna treat. Aprilia’s Superbike boss Giuseppe Bernicchia discussed with WSB tech inspector Steve Whitelock the move to “restore parity” between 750cc Fours and lOOOcc Twins. From his gestures, it was clear he fears a performance seesaw as various measures are tried. Might WSB adopt a straight lOOOcc displacement limit with only Supersport-type engine mods, as has been done in the World Endurance Championship? This would wipe out the Italians at a stroke, so now the “stability rule” has been invoked. This requires a three-year comment period before major equipment changes can be adopted.

World Superbike will likely remain as it is until 2004.

I talked briefly with Ducati’s Corrado Cecchinelli, who is Claudio Domenicali’s colleague in engine development. I asked about the 2000-season shift from three injectors per intake stack to a single “showerhead” injector. The older system delivered off-idle smoothness from a small vernier injector under the throttle plate, plus a second, larger injector at the same level, with a showerhead above the open bellmouth for high-rpm operation.

He replied that the goals of the change were first, to permit shortening of the intake length to boost top-end power, and second, to permit the airbox to be simplified and “cleaned-up.” I presume this means that, with only a single top injector, the floor of the airbox could be lowered toward the engine, gaining volume.

“The problem of the single showerhead,” he explained, “is that idle fuel from it accumulates on top of the throttle plate (during closed-throttle running). When the rider begins to turn the throttle, this fuel enters the engine, causing a hesitation.” Why not just cut off fuel completely on closed throttle? Because this produces an even bigger hiccup!

This made me think of the Aprilia throttle body, with its smooth, lens-like throttle plates. Are they made smooth like that in part so they shed fuel easily?

Cecchinelli said that solving this problem required much running on motoring dynos (which drive the engine with a big electric motor) able to simulate highspeed overrun. The single injector was proven in the Italian national series during 1999, then moved to WSB for 2000.

He spoke of the need to attain high power without compromising powerband smoothness. This is difficult, “because for power, the engine needs big valves and ports, a short intake and long cam timings. But all these things make the engine brutal, so a great deal of work is necessary.”

I observed aloud that Ducati’s policy of incremental development of a single basic design has accomplished a great deal. “And there is more to come,” he replied, smiling.

The AMA 600cc Supersport race on Saturday showed Eric Bostrom’s new strength. On lap one he split to the tune of a 2.7-second gap, then pulled away to win by nearly 10 seconds. This is > unusual in the 600cc class, where riders, power and setup are always nearly equal. Not today.

AMA Superbikes also took to the grid on Saturday. A group of six pulled away, Jamie Hacking at their head, National number-one Mladin, struggling with faulty gear selection, at the rear. Suzuki’s Aaron Yates soon took the lead and moved off on his own, only to high-side spectacularly, breaking arm and wrist. This left Hacking in the lead, followed by Honda’s Miguel Duhamel, Bostrom and Mladin. The rest of the race became a relentless stalk of Miguel by Eric, who was brake-sliding the back of his Kawasaki into Turn 2 and everywhere else in breathtaking swoops. His style is to turn at high speed, holding the machine as upright as possible by hanging off the inside-and staying there for the first phase of acceleration to get quickly onto the meat of the tire. Under this pressure, Duhamel’s rear tire signed off and began to slide. At the finish it was Bostrom by just under 2 seconds from Duhamel, then Mladin, Hacking and Chandler. Bostrom had once said that he’d only consider he’d truly won a national when he’d “beaten Miguel straight up.” This was it.

The Suzukis made progress from last year. Then, Mladin had spun over the Turn 11 exit bump, losing drive he needed to stay with Nicky Hayden’s Honda. This year, although all three Yoshimura Suzukis still warbled over this bump, they didn’t spin outright. Mladin added his “supplemental suspension,” springily carrying most of his weight on his feet here, just as he had over Loudon’s harsh Turn 12 pavement transition a month earlier. The Hondas have gone backward-gaining power, losing traction and tire-friendliness. What a difference a year makes.

Last year Ben Bostrom said of his riding style, “My way will prevail.” It did on Sunday, even though he is only fourth in the series, 79 points down from Bayliss. Braking into turns, Bostrom’s rear wheel oscillates threateningly from side to side, 1-2-3, as almost all the weight is thrown onto the front tire. Europeans describe his setup as “loose,” meaning that his bike lacks directional stability in comers and has soft suspension. An accident of his dirt-track background? When Gary Nixon showed us in 1976 that he could brake with the rear wheel smoothly hovering 1 -3 inches off the pavement, I wondered how he did it. Bostrom obviously finds the rear-end swing comfortable-it tells him the back end is properly light yet still in control. Now the softness: For grip, soft is good, but for launching quick maneuvers, stiff is better. What’s the choice? Mladin likes it stiff to the point of sacrificing grip over rough pavement. Bostrom wants the grip and compensates with quick steering geometry and his own high tolerance for instability. Lack of direction? He revels in it, as it allows him to change line in comers. The bike looks squirrelly but goes fast. Bostrom’s way may indeed prevail.

His poor start in Sunday’s WSB Race One put him behind Hodgson, Corser, Bayliss and his brother Eric. It would take Ben 22 laps to prevail, winning by 1.3 seconds over those same riders.

In Race Two he was away second and leading by Turn 2, taking over from Neil Hodgson. “I drove it in there big,” said Ben of his pass. By lap five the race settled into a distance-holding affair between Bostrom and Corser, as Hodgson chased in vain.

“I was trying to cruise around,” Bostrom said later, “but there was Troy coming at me.”

He hung on just fine and beat Corser. Hodgson was third, with Bayliss and Eric in his wake. Alternately grinning and looking exhausted in the post-race press briefing, Ben said after his firstever WSB double win, “I’m trying to match my brother-he’s on a roll too!”

A fine Bostrom family weekend. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue