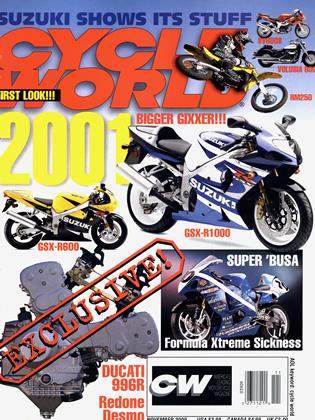

SUPER 'Busa

Something wicked this way's fun

MARK HOYER

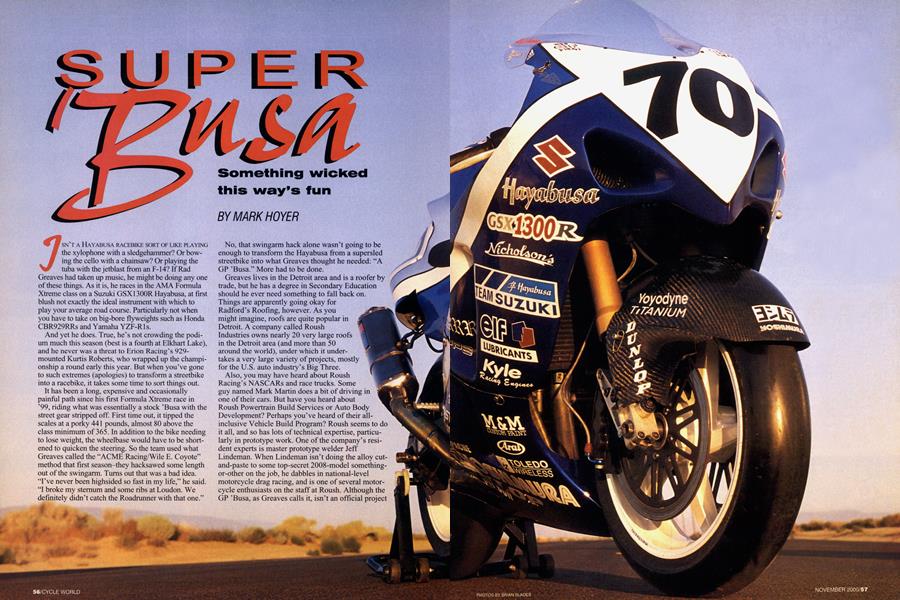

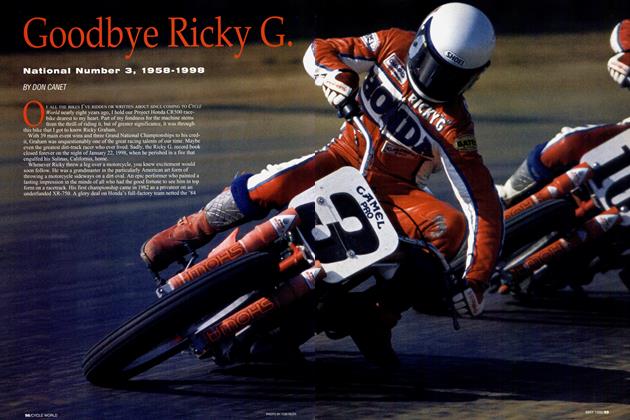

ISN'T A HAYABUSA RACEBIKE SORT OF LIKE PLAYING the xylophone with a sledgehammer? Or bowing the cello with a chainsaw? Or playing the tuba with the jetblast from an F-14? If Rad Greaves had taken up music, he might be doing any one of these things. As it is, he races in the AMA Formula Xtreme class on a Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa, at first blush not exactly the ideal instrument with which to play your average road course. Particularly not when you have to take on big-bore flyweights such as Honda CBR929RRs and Yamaha YZF-R1s.

And yet he does. True, he’s not crowding the podium much this season (best is a fourth at Elkhart Lake), and he never was a threat to Erion Racing’s 929mounted Kurds Roberts, who wrapped up the championship a round early this year. But when you’ve gone to such extremes (apologies) to transform a streetbike into a racebike, it takes some time to sort things out.

It has been a long, expensive and occasionally painful path since his first Formula Xtreme race in ’99, riding what was essentially a stock ’Busa with the street gear stripped off. First time out, it tipped the scales at a porky 441 pounds, almost 80 above the class minimum of 365. In addition to the bike needing to lose weight, the wheelbase would have to be shortened to quicken the steering. So the team used what Greaves called the “ACME Racing/Wile E. Coyote” method that first season-they hacksawed some length out of the swingarm. Turns out that was a bad idea. “I’ve never been highsided so fast in my life,” he said. “I broke my sternum and some ribs at Loudon. We definitely didn’t catch the Roadrunner with that one.”

No, that swingarm hack alone wasn’t going to be enough to transform the Hayabusa from a supersled streetbike into what Greaves thought he needed: “A GP ’Busa.” More had to be done.

Greaves lives in the Detroit area and is a roofer by trade, but he has a degree in Secondary Education should he ever need something to fall back on.

Things are apparently going okay for Radford’s Roofing, however. As you might imagine, roofs are quite popular in Detroit. A company called Roush Industries owns nearly 20 very large roofs in the Detroit area (and more than 50 around the world), under which it undertakes a very large variety of projects, mostly for the U.S. auto industry’s Big Three.

Also, you may have heard about Roush Racing’s NASCARs and race trucks. Some guy named Mark Martin does a bit of driving in one of their cars. But have you heard about Roush Powertrain Build Services or Auto Body Development? Perhaps you’ve heard of their allinclusive Vehicle Build Program? Roush seems to do it all, and so has lots of technical expertise, particularly in prototype work. One of the company’s resident experts is master prototype welder Jeff Lindeman. When Lindeman isn’t doing the alloy cutand-paste to some top-secret 2008-model somethingor-other on the job, he dabbles in national-level motorcycle drag racing, and is one of several motorcycle enthusiasts on the staff at Roush. Although the GP ’Busa, as Greaves calls it, isn’t an official project for the company, the man himself, Jack Roush, gave the okay for after-hours mucking about. Lindeman had done the first swingarm mod, and handled this season’s considerable chassis alterations.

Ultimately, 3.5 inches was removed from the wheelbase, reducing it from 58.7 inches to 55.2, right in line with his Rl and 929 competition. Plenty of that length came out of the frame, although the Suzuki GSX-R750 race-kit swingarm is shorter than the stock Hayabusa piece. Anyway, you probably could build a mobile home with the scrap from the healthy slices of chassis material removed. Lindeman whipped up his own jig and made all the measurements by hand for this work. When Greaves took the frame to GMD Computrack to verify that it had been stuck back together straight, it was a miniscule .002-inch off the previous measurement-virtually perfect. All by hand. As for the actual rake and trail, Greaves didn’t want to reveal the numbers, but told us that the rake is steeper than his stock bike’s measurement of 24 degrees, and the trail has been increased from the original 3.8 inches. We wondered why he was afraid of giving us the numbers-was it all the other guys out there waiting to cut their Hayabusas in half? In any case, a racer’s setup information is hard-won stuff, so guarding it is understandable.

Engine mounts were moved forward to make the biglump torque-reactor powerplant fit in the truncated frame, which in turn necessitated moving the oil-cooler-now fouling the front tire-from in front of the engine to the tailsection. That’s the reason for the odd, nostrillike openings in the big rear hump-airflow.

After all this chassis work, Greaves was still using the stock shock linkage, and it just didn’t feel right. That led to Yoshimura coming up with the single most effective chassis-tune: A new link designed by Yosh race-team data-acquisition expert Amar Bazzaz, who analyzed the Super ’Busa’s new frame geometry, probably hung it on some freaked-out mathematical handling construct, then built a little computer file Greaves took to his Roush buddies to use for fabrication of the piece. The finished link was fitted for a winter test at Willow Springs and immediately cut 2 seconds off his previous best lap, Greaves citing a much more predictable slide quotient as well as increased rear grip as the main benefits of said link.

Another chassis is in the works (GP ’Busa II, he calls it) that’s even shorter from steering head to swingarm pivot. It’s so stubby there are recesses in the frame spars for the valve cover, and a new, thinner, curved radiator will be required. But that’s the future.

The rest of the chassis stuff is typical race hardware: Öhlins suspension front and rear (the fork was a measly $7000), Marchesini wheels, Yoshimura clip-ons, Attack Racing adjustable triple-clamps and so forth. Dry weight is 388 pounds on Of s certified scale, still some way over the class minimum, though certainly not bad for a machine that started life as a 521 -pound streetbike.

To develop the bodywork for this season, Rad & Co. tried to sneak the ’Busa in on the tail end of one of the $l0,00()-an-hour Detroit windtunnel sessions booked by the car companies. So far, though, everybody’s used all their allotted time-even if you were just flying a kite, wouldn’t you use up each and every one of your $ 167 minutes? Anyway, the nice thing about the Roush connection is that even without getting actual windtunnel time, Lindeman can pick up the phone and dial up one of his buddies across the room for a little advice. It was at the suggestion of one of the wind engineers that the tailsection should be as tall as possible, and that there should be a “beak” on the nose of the fairing protruding downward to divert air from the negative pressure zone above the front wheel. This has actually exaggerated the lines of the stock bike. Wait, is that possible? I always thought the Hayabusa styling was like 200proof alcohol-it doesn’t come any stronger, and while you may not like the taste, what it does is pretty interesting, so you put up with it. Even get to like it.

At just past 5 a.m. on our Willow Springs test day, I crawled bleary-eyed to the front desk of the Palmdale Holiday Inn to check out. There’s a good amount of aerospace development undertaken in the area (Palmdale, not the front desk-trust me, this guy was no rocket scientist), and so pictures of SR71s and various fighters are hung on the walls here, thanking the place for its support. 1 looked to the left and saw a photo of a guy in a rocket-powered ejector seat. He was shooting skyward with flames coming out his ass, and there was a parachute deploying from the top of his seat. “Parachute? What a wussf I thought. The prospect of riding a racebike with 186-horsepower and 108 foot-pounds of torque made a rocket chair with a parachute look like my living-room recliner with a scotch next to it.

Prior to the test, I’d called around to try to get my leathers lined with asbestos (and maybe a diaper...), due to the threat of low-orbit highsides and the subsequent re-entry. “Will you be needing an oxygen system, Mr. Hoyer?” Perhaps.

The single greatest threat to my personal safety would probably come after the crash, though, when Greaves realized I’d cartwheeled his $70,000 (labor not included) racebike deep into the desert.

Okay. Let’s go. Because go is what we’ve got. For our test we had the “torque” engine installed, still in situ from the Pikes Peak National a few days before. This bored-out, hopped-up powerplant (“in the 1300s,” says Greaves coyly) yields the aforementioned 186 horsepower. There is also a nearly stock engine for rain use. Then there’s “Big Daddy,” a bored-and-stroked, 1400-something-cc monster that was ported and built at Roush. It was dynoed elsewhere at 204 bhp. He uses this one for special occasions like Brainerd and Elkhart Lake-big, fast tracks that reward that kind of sick excess.

It was a sunny and surprisingly cool, wind-free morning at Willow. After a few laps on our long-term 1999 Hayabusa brought along for comparison, I sneaked up on the racebike and jumped on board, hoping the element of surprise wouldn’t allow it to retaliate against me in the forthcoming laps. It was apparently indifferent to me. The bike felt a lot taller in the seat than the stocker and the widely set clip-ons were a much shorter reach. Footpegs were racebike high.

Thankfully, the only thing to come out of me after the first six laps aboard this monster was a burbling fountain of incoherent babbling, which, not being that unusual, surprised no one. Then I muttered, “That is absolutely beyond reason.” So I took a little rest, sipped a nice, cool iced tea in the shade while Road Test Editor Don Canet went out to do a few effortless wheelstands for the camera. I mulled over the experience and tried to recalibrate my brain so that I might take better advantage of this motorcycle. Lest it take advantage of me.

My brief ride suggested that, yes, this was a very fast motorcycle, but also that it handled pretty well for something cut in half and stuck back together. I asked Greaves about this, and he said that early in his career he didn’t really have any engine-builder connections, so he always concentrated on chassis development, ultimately getting to the point where he feels he can dial-in a bike quickly.

Time to get serious. Successive laps brought greater comfort and more and more confidence in the bike. “The faster you go, the smoother it will get,” Greaves had said. The suspension is very stiff and grip from the 16.5-inch Dunlop slicks (God's own tires...) was absolutely unbelievable. Tightening the cornering line was always an option, and there was a lot of feedback from the chassis.

After about 12 serious laps, my hands were numb, my feet were numb, and my eyeballs were getting inflamed from being smashed on every comer exit. This bike has the kind of effortless lunge that brings on the next comer so fast it causes tunnel vision. Or was that the g load sucking the blood out of my head? Squeeeeeeze like a fighter pilot... must... remain... conscious. Warping out of Turn 1 near the end of my second session, I really hit the afterburners and couldn't believe how fast Turn 2 was approaching. I looked at the tach because surely it was getting close to 10,800-rpm shift time: Just 6500 rpm showed! So that’s what 108 foot-pounds of torque is good for.

Canet cut some laps and was wheelying on the exit of Turn 1. Then Turn 2. He said later he could wheelie off any turn except 8, which is hardly a turn at all. Well, it’s hardly a turn until you ride a 186-bhp, 388-pound racebike toward it as the bars shake in your hands and your backbone compresses against the tailsection. Then it starts looking a little tight. The whole of big, fast Willow Springs looks tight on this thing. The stocker we brought along felt like a marshmallow stuck in molasses by comparison. It’s hard to believe he started with a bike identical to ours.

Still, Greaves complains about the same trouble we have had with our long-termer in use on the racetrack-not enough brakes, or rather too much weight for the stopping power. So it is during braking that he feels he loses the most ground in racing. The PFM six-piston calipers on the Super ’Busa are actuated by an AP master cylinder and haul the beast down with impressive authority. The big floating discs performed consistently, were very “feelly” and didn’t fade. Still, Greaves says with the nearly 30 more pounds his bike carries compared to his competition, he just watches helplessly as his opponents run it in deeper. He then added with a smile, “But it never lets you down on corner exits.”

Ah, no, it doesn’t. Twist the throttle, my friend, and you shall arrive in the future. Now. Canet came back from his speedy outing, took off his helmet and smiled. “This thing is so much fun exiting Turn 6! You just get a nice, progressive wheelie down the hill. I can see how you'd get addicted to the power. It’s so tempting to use the midrange torque. The drawback to that is that there’s thousands of rpm left before redline. If the rear lights up and steps out, you’re going to have a hard time saving it. As weird as it sounds, this is the kind of bike I’d ride high in the rev range, near redline, exiting corners. That way, if it lights up suddenly you run into the rev-limiter, which is a good-softer-way to control wheelspin than trying to back out of the throttle.”

I’ll take his word for it.

Despite the insane engine performance on tap, it really was rather docile overall-just don’t whack it all the way open. Stock fuel-injection and engine management is retained, with a Dynojet Power Commander II used to reprogram fuel delivery and ignition timing. Throttle response is good, and twist effort is light, just like stock. Very nice. It’s a beast of a motor, but not a vicious one.

As for the handling, Canet was more reserved in his praise than I was, but he’s got a much better perspective on how racebikes feel. “It tended to wallow and shake its bars a little more than I like,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, it’s a pretty common thing on a racebike, but I’d work to try to eliminate it if I could. Sometimes you can’t. But it’s impressive, especially considering what he started with. Actually, it reminded me a little of the old GSX-R1 100 endurance bikes I used to race.”

I’d noticed the bars wagging in comers, particularly over the crest of 6 and the Turn 7 kink to the left, but it was really pronounced accelerating hard up the front straight. Sitting back on the seat, on the advice of Greaves, steadied the bike in a straight line, but it never really settled down completely. This was about the only negative.

By the end of the day it became easy to relax on the bike, and I was just draping myself over the hand-made aluminum tank (a mere $6000, from Fujio Yoshimura, son of Pops himself), keeping my body relaxed and letting the machinery do all the work. There had been genuine fear creeping up my spine at the prospect of riding this bike, the kind of feeling that sits at the edge of your consciousness and keeps you from sleeping as well as you might. It becomes acute, gripping, as the beast lies before you, the low growl of its 1500-rpm idle vaguely threatening, suggesting unknowns pregnant with danger.

Turns out this overhorsepowered Super ’Busa isn’t the wicked instrument of destruction I thought it would be-this sledgehammer works. One thing’s certain: If Rad ever takes up music, no xylophone is safe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGp Four-Strokes

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson