CRITICAL MASS

RACE WATCH

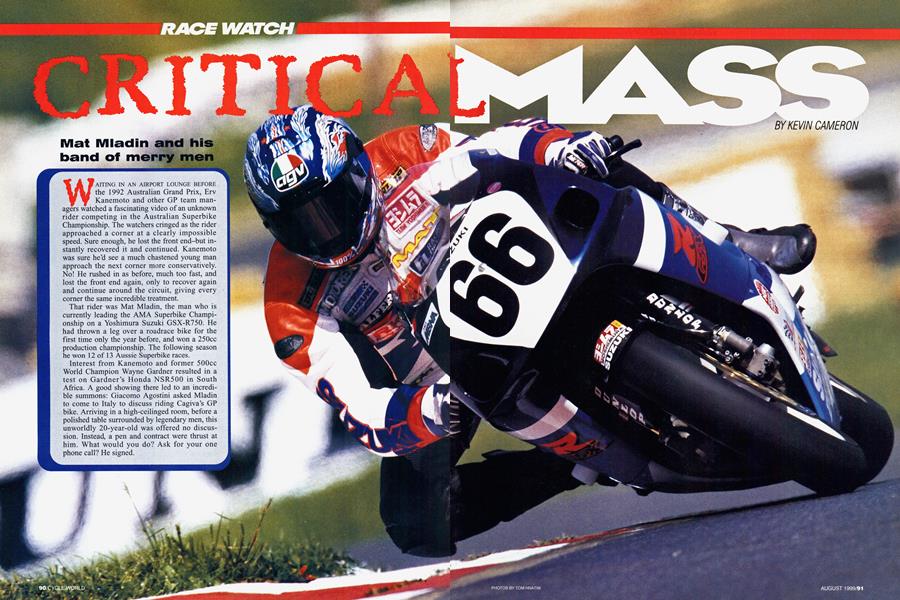

Mat Mladin and his band of merry men

WAITING IN AN AIRPORT LOUNGE BEFORE the 1992 Australian Grand Prix, Erv Kanemoto and other GP team managers watched a fascinating video of an unknown rider competing in the Australian Superbike Championship. The watchers cringed as the rider approached a corner at a clearly impossible speed. Sure enough, he lost the front end-but instantly recovered it and continued. Kanemoto was sure he’d see a much chastened young man approach the next corner more conservatively. No! He rushed in as before, much too fast, and lost the front end again, only to recover again and continue around the circuit, giving every corner the same incredible treatment.

That rider was Mat Mladin, the man who is currently leading the AMA Superbike Championship on a Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750. He had thrown a leg over a roadrace bike for the first time only the year before, and won a 250cc production championship. The following season he won 12 of 13 Aussie Superbike races.

Interest from Kanemoto and former 500cc World Champion Wayne Gardner resulted in a test on Gardner’s Honda NSR500 in South Africa. A good showing there led to an incredible summons: Giacomo Agostini asked Mladin to come to Italy to discuss riding Cagiva’s GP bike. Arriving in a high-ceilinged room, before a polished table surrounded by legendary men, this unworldly 20-year-old was offered no discussion. Instead, a pen and contract were thrust at him. What would you do? Ask for your one phone call? He signed.

KEVIN CAMERON

Today, Mladin says it was an education to be on the GP grid, albeit 2.5 seconds off the pace with no idea of what to do. As a novice season, it was still a promising performance, with a best finish of sixth in the last race of 1993. Gardner reckoned that it would take two years to learn the tracks and become comfortable with the life. But Cagiva clearly expected Mladin to be their messiah, a miracle worker who could transform their bike from an immature design into a dominant force. Predictably, it did not happen. When you disappoint an Italian team, you soon find yourself riding junk, a parts bike.

When I spoke to Mladin at Laguna Seca at the end of 1996, he said mildly of his Cagiva experience, “I don’t regret it. I learned something from it.” Today, he believes his early Australian successes came from physical fitness and an aggressive riding style. At the world level, however, everyone is fit and aggressive-and they have the necessary experience.

After a difficult two-year period, punctuated by injuries and long recoveries, Mladin signed with Yoshimura

to contest AMA Superbike. He placed fourth. The following year, he rode a Fast By Ferracci Ducati, winning four AMA nationals and finishing third in the title chase. He lost points, as he saw it, from reliability problems-es-

pecially at Daytona, where Twins traditionally do not finish well.

Last year, he returned to the Yosh squad, despite that team's long period of uncompetitiveness. Result? Seven poles, one win and another third over-> all in the championship. Recent Suzukis have been tire-eaters, due partly to a steep powerband. When that was addressed, chassis setup remained elusive-possibly a result of the team having been off the pace for years. Journalists have become accustomed to hearing the blue-and-white bikes damned with faint praise by their riders. “It’s got potential,” they say. “It’s way better than it was.”

Now, Mladin is leading the title chase, taking firsts and seconds. What has changed now, I asked him? Mladin

is a clear, forthright speaker, never at a loss for words. “I have a really good team,” he says. “I have Reg O’Rourke putting the bike together. When I go out on the bike, I know it’s right, everything’s lockwired, nothing is going to fall off.”

O’Rourke is the chassis man. The engines are built by veteran Yosh staffer Minoru Matsuzawa, better known as “Matsu.” Pat Cahill rounds out the mechanical staff. “Then, there’s Ammar Bazzaz,” Mladin continues. “Ammar has a degree in math-

ematics, and when I have a problem on the track, he and I go on the computer for half an hour and look for a way to fix the problem. A lot of the time, it’s worked.”

Mladin’s team is wonderfully international, much like Formula One auto-racing teams. As one insider put it, “We have an Australian rider of Croatian descent riding a Japanese motorcycle, with an Iraqi engineer, in a U.S. racing series.”

I called Bazzaz to learn more about this rider/engineer collaboration. The first thing I learned is that, although his name may be unfamiliar, his speech is thoroughly American. He is a graduate of the University of Massachusetts. Bazzaz solicited race teams for a job in data acquisition two years ago because he wanted to leave academic work for something more exciting and open-ended (he is a long-time mo> torcycle enthusiast). He got that in spades when Yoshimura said yes. He soon found himself drafted into Mladin’s personal team in the unfamiliar but fascinating role of vehicle dynamics engineer-pretty different from atmospheric research instrumentation!

Despite all the technology that goes into a modern racebike, handling setup

is still not widely practiced as a physics-based activity. After all, traditions die hard. “That’s just how we do it,” is the explanation Bazzaz has heard too often for “answers” that don’t make physical or mathematical sense.

Traditional setup begins with The Notebook, in which the settings for all previous races are (hopefully) written down. Looked at in one way, the book is good because it preserves valuable knowledge. Looked at another way, it guarantees that each race practice be> gins with bolting on last year’s mistakes. Moving ahead requires more creative alternatives-physics rather than tradition.

Says Bazzaz, “Often, (the discussion is) something as simple as, ‘When

should I shift?’ or ‘Should I stand it up sooner here?’ Mat was brought up in the old school of, if it’s not fast enough, ride it harder. Now, we look at how the motorcycle works, and he adapts to the characteristics of the motorcycle. His involvement with the computer really helps.”

“I like start/stop tracks where you get through the turn and out fast,” Mladin told me. “Laguna Seca’s not like that. I had to slow down to go fast there, and I set a new lap record there last spring.”

This means that he deliberately changed his riding style in order to go faster at Laguna. That’s impressive because for many riders, riding style is not a modifiable series of conscious acts, but a subconscious reflex that resists change. A rider’s style, after all, is his main protection against danger.

The ability to think analytically about how to go faster (the computer helps here), and the ability to smoothly integrate those changes into fast laps are

rare qualities. Other talented riders can change their styles in this way only for a few laps in practice, at a cost of intense concentration. Because in the heat of competition they cannot afford such concentration, they revert automatically to their old ways-and slow down.

Mladin did, as he has said, learn a lot from his Cagiva experience. First, that there is more to racing than being in shape and determined. Second, that being miserable at racing’s highest level is still misery. There’s more to life than a GP contract-New Zealander Graeme Crosby, an exciting, intense man, quit GP racing because he found it too corporate, too confining. “If you’re not having a good time, it’s not worth it,” Mladin observes.

Some people were surprised that Mladin signed a three-year contract with Yoshimura to continue riding Superbikes in the U.S. They ask, “Where’s his ambition to reach the top-you know, 500s?” Mladin is a realistic man and not a romantic boy. He knows when he is well off. Right now, he says his aim is, “Being happy and living the life I want to live.” A GP ride may have been the ultimate achievement in years past, but it's less clearly so today.

The future of the series looks uncertain, and current sponsors tend to be nationalistic. Good men have used themselves up in the striving. Knowing what he knows, Mladin can’t allow himself the luxury of this striving. Indeed, his manner at the track is one of carefully controlled understatement, even indifferencelike a man remaining elaborately calm while placing a large bet. When he sets pole time-as he often has-he is first to point out that poles and wins are different. When he won Loudon in 1997, all he could say was, “I never really got comfortable on the bike.” Everything about Mladin’s outward self says evenly, “I can handle it.”

When emotions run high, as they did over the restart at the recent Laguna Seca National, Mladin speaks his mind and lets it be known that he is angry, and at whom. In that case, he felt it was wrong for the AMA to negate the many laps completed be-

fore the red flag, transforming the race into a seven-lap trophy dash. Whatever his feelings, he then went out and coolly nailed down the second place that he had earned before the race was stopped.

The partner of this extreme selfcontrol is his realism. Of Anthony Gobert’s dominance of that race,

Mladin said there was nothing he could do about it on that day. Later he would say, “I’m here to win a championship, and this championship doesn’t pay hanging it all on the line.”

That is to say, yes, he might have challenged Gobert harder and perhaps won, but he might as easily have fallen and lost everything. Crashing in romantic pursuit of the unattainable is something that Mladin is content to leave to others. Meanwhile, he can be happy with second-place pointsand the series lead.

As to the level of competition in the U.S., Mladin says, “You just wait ’til (Laguna Seca) World Superbike and see the results. I’ll be very surprised if a couple of us don’t get up there (on the podium). I don’t think there’s a whole lot of good riders in World Superbike. Take the top six: Carl Fogarty is the only one who’s always there. Carl is the guy. I see no reason not to beat the others.”

Mladin clearly respects Gobert’s talent, and used it to further illustrate the > competitiveness of the U.S. series. “Anthony has more natural ability than anyone-maybe ever-so much that he was able to win World Superbike races on an uncompetitive Kawasaki. Now, he’s on a factory Ducati, but he’s not winning all the time.”

He went on to say that Gobert’s gift is so great that he seems not to think about it, or try to manage or improve it. This brings to mind the early-’80s rivalry between Eddie Lawson and Freddie Spencer. Spencer was naturally brilliant, but Lawson was grimly determined and a hard worker. Spencer set fast times with apparent ease, but Lawson was always right behind, improving steadily, coming always closer. Spencer won more races. Lawson won more championships.

Even the most brilliantly designed motorcycle cannot win races without mutual adaptation of man and machine. The longest runs of racing success have always resulted from the intimate tailoring of powerband and handling to one outstanding rider. Two notable examples are Kenny Roberts and the Yamaha YZR500 in the late 1970s, and

Mick Doohan and the Honda NSR500 today. This specialized tailoring often goes so far as to compromise the machine’s usefulness to other riders.

When the top rider retires, the design and setup of his machine are enshrined as engineering truths, rather than understood as the accident of one man’s style. Later riders go poorly when these engineering truths don’t work equally well for them. It takes time for a new champion to make a place for himself in spite of this social problem. Yamaha and Suzuki have recovered only recently in GP racing after the loss of their great riders Wayne Rainey and Kevin Schwantz. How? Either the new rider’s prestige must be so great that factory race engineers will cooperate with him (Max Biaggi at Yamaha), or the new rider must bring his own engineer (Suzuki’s Kenny Roberts Jr. and Warren Willing). The process of recovery reaches critical mass when improved results lead to improved cooperation, leading to improved results, and, well, you get the picture.

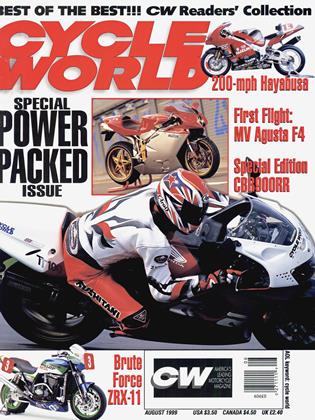

We’ve all admired Suzuki’s GSXR750, and wondered why it has never attained its potential in AMA Superbike. Could it be that Mat Mladin and his merry men have reached critical mass? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGo Show

August 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcyclist's Calendar

August 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBackmen

August 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupCagiva's Monster Musclebike

August 1999 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBuell's Total Recall

August 1999 By David Edwards