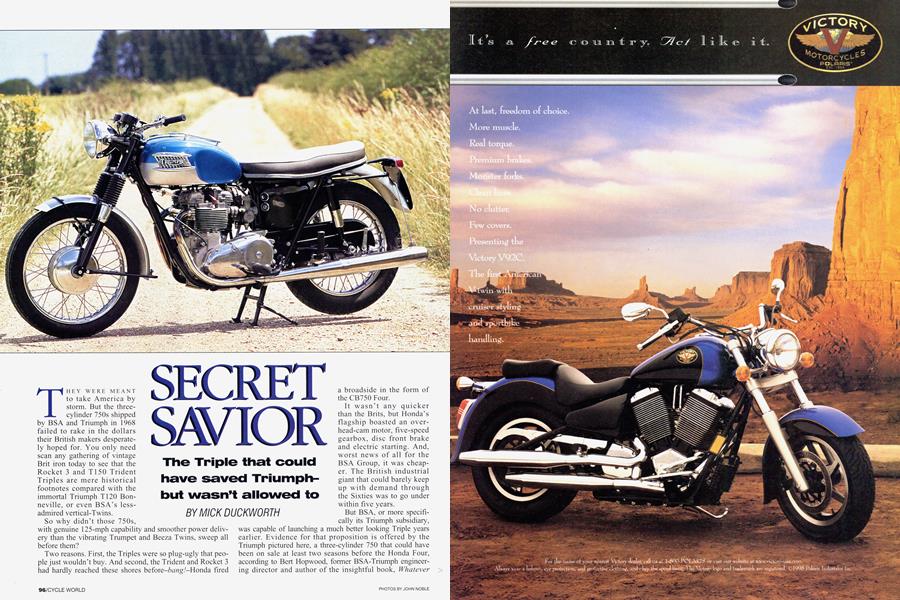

SECRET SAVIOR

The Triple that could have saved Triumph-but wasn’t allowed to

MICK DUCKWORTH

THEY WERE MEANT to take America by storm. But the three-cylinder 750s shipped by BSA and Triumph in 1968 failed to rake in the dollars their British makers desperately hoped for. You only need scan any gathering of vintage Brit iron today to see that the Rocket 3 and T150 Trident Triples are mere historical footnotes compared with the immortal Triumph T120 Bonneville, or even BSA's less-admired vertical-Twins.

So why didn’t those 750s, with genuine 125-mph capability and smoother power delivery than the vibrating Trumpet and Beeza Twins, sweep all before them?

Two reasons. First, the Triples were so plug-ugly that people just wouldn’t buy. And second, the Trident and Rocket 3 had hardly reached these shores before-bangl-Honda fired

a broadside in the form of the CB750 Four.

It wasn’t any quicker than the Brits, but Honda’s flagship boasted an overhead-cam motor, five-speed gearbox, disc front brake and electric starting. And, worst news of all for the BSA Group, it was cheaper. The British industrial giant that could barely keep up with demand through the Sixties was to go under within five years.

But BSA, or more specifically its Triumph subsidiary,

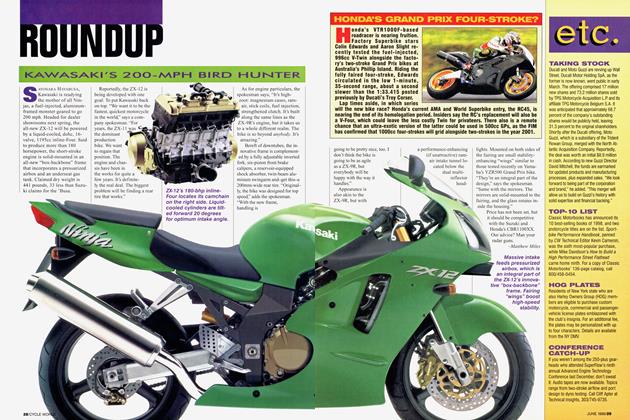

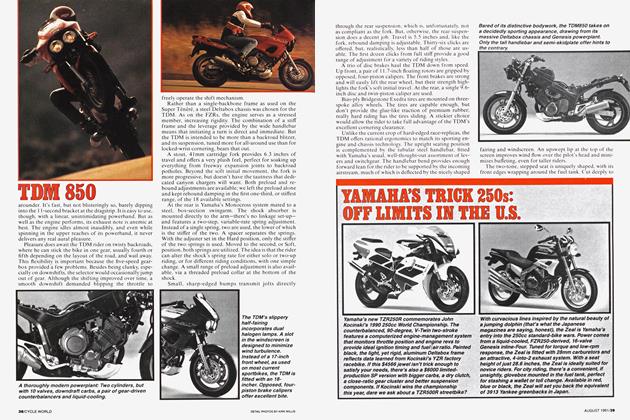

was capable of launching a much better looking Triple years earlier. Evidence for that proposition is offered by the Triumph pictured here, a three-cylinder 750 that could have been on sale at least two seasons before the Honda Four, according to Bert Hopwood, former BSA-Triumph engineering director and author of the insightful book, Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry?

This is a reconstruction of a prototype simply coded PI. Its 748cc motor, thought to be one of only three, was assembled at Tri-

umph’s Meriden factory in 1964 or 1965.

Found languishing under a workshop bench four years ago, it has been installed-as it originally was-in a slightly altered Bonneville rolling chassis.

The PI prototype’s revival is the work of keen historians in the U.K.-based Trident &

Rocket 3 Owners Club, who having unearthed the engine, were determined to recreate a functioning bike. No other example survives and the only clear references available were a couple of photos in Hopwood’s book.

The original idea, as Hopwood relates, was for Triumph to target a new roadburner on America with more cubes, less vibration and a top speed of at least 120 mph. Hopwood and right-hand man Doug Hele had embraced the Triple concept as far back as 1962. The two worked together at Norton in the late Fifties, when one of their tasks had been to meet U.S. calls for full-on 750s. British factories had traditionally seen 500cc as the premier class, but demand for bigger engines from the

Yanks in the post-war period led them to enlarge basic halfliter parallel-Twins to 650cc.

But Hele and Hopwood knew that an unbalanced 750 Twin tuned for high performance would vibrate horribly. They only managed to make the 1962 Norton Atlas ridable by fitting softer cams and lower-compression pistons than they’d originally wanted.

At the time, a Four was discounted, not merely on cost, but on the assumption that the compactness, lightness and agility that sold Britbikes would be lost. They decided the solution might lie in an inline-Three, providing power more smoothly than a Twin without too wide an engine. With few motorcycle precedents, the layout was at least known to work in Saab automobiles, albeit with a two-stroke engine. So, when Hele followed Hopwood to Triumph to become Meriden’s development chief in October of ’62, he was encouraged to pursue the idea.

A Triple was drawn up with a 120-degree crankpin layout and the same 63 x 80mm

bore and stroke as Triumph’s old-style pre-unit 500s-a long stroke would help keep the engine narrow. To create an experimental unit easily and rapidly it was laid out like a typical ohv Triumph, but with an extra cylinder and an added center section in the vertically split crankcase.

The first PI engine was bench-tested early in 1964 with encouraging results. Best figures were very close to 60 bhp at 7250 rpm, an instant 15 percent gain over the 650. But the Triple project was viewed with skepticism by Triumph boss Edward Turner, creator of the high-earning Twins, and it was given no official role in overall BSA Group policy.

When the P1 took to the road for mileage testing, snags included heavy wear at the two plain bearings supporting the crankshaft on either side of the middle cylinder. And overheating distorted the cylinder-to-head joint, so the cheap iron block was junked in favor of alloy. To prevent a buildup of lubricant in the bot-

tom-end, an extra oil compartment for the dry-sump system was welded to the lower crankcase. Another problem was that the trio of gears taking primary drive to a T 120-type clutch placed inboard of them was unacceptably noisy.

The Pi’s single-coil ignition system relied on a distributor driven by skew gears from the intake camshaft, with its near-vertical shaft continuing down into the crankcase to propel a gear-type oil pump. The contact breakers were in the T120 location at the timing-side end of the exhaust camshaft. A trio of Amal’s then-current Monobloc carburetors with l5/i6-inch bores was mounted on flexible intake hoses. The outer two instruments had their float chambers removed so they could fit in the restricted space. A single cable from the twistgrip ran to a 3-into-l junction box under the gas tank.

Performance potential was not in doubt. The PI tore up rear tires and Meriden testers reported that it could be held at 120 mph for long spells. Riding the recreated early Triple

today confirms that its behavior reflects its appearance, being like a Twin in some respects and a production Trident in others. The exhaust sound is totally Triple, a hoarse growl like that of the nowlegendary “Beezumph” roadracers of the 1970s.

As per Hopwood’s book, the mufflers are Thruxton Bonneville items, but in tests the PI ran larger cans. Prototype routing of three pipes into two, with a stub from the center port meeting a crosstube, is neat but clearly not very efficient.

Off the bottom, the replica’s engine has sufficient torque to pull happily from little more than 2000 rpm. This Bonneville-like grunt, markedly greater than the standard T150’s, is presumably due to the longer stroke. As revs rise this engine feels significantly more potent than the Twin, with satisfying thrust delivered from 4000 rpm up, giving a similar ride to the Trident. Delivery is definitely smoother than a Twin, although tingling vibration comes through the seat at times. As on the early Trident, there are four gear ratios.

Apparently unfazed by carrying an extra 45 pounds or so, the frame handles capably. Pushing the PI hard enough to scrape the footrests in turns fails to unsettle it, but there is a slight squirm in the fork when pulling up under heavy braking. Extra power and bulk do tell on the T 120-style 8-inch front drum, replaced by a twin-leader on production Triples. Pleasantly leaner and sleeker than the bulky, slab-sided Trident, the PI is relatively easy to maneuver and park.

The prototypes’s primary-drive gears disappeared long ago, so the machine was restored with a chain primary drive and a ’60s Greeves racer clutch. It’s operated by a pushrod passing through the gearbox mainshaft, unlike the later Triple’s short pull-rod system. Rigging the original ignition proved nearimpossible, so a modern Boyer Bransden electronic unit and three coils are hidden under the seat. Take-off for the rev-counter is

from the drive-side end of the exhaust camshaft, made possible by altering the left sidecase. The brass hexagon plug on the PI replica’s rightside timing cover was fitted for crankcasebreathing tests.

The tidy “1965” PI shown in Hopwood’s book was probably a mockup, rather than a working prototype which would have been roughly finished and badgeless to preserve anonymity. But the T&R30C cannot be blamed for wanting their treasured possession to look neat, showing what might have been in Triumph showrooms in the midSixties. Club members reunited Doug Hele with his baby in 1998, but unfortunately Bert Hopwood died three years ago.

years ago.

If the BSA Group had solidly backed Triple development early in 1963, it surely could have launched a sound 750 with handsome looks three years later. Such a machine would have been sensational, being by far the fastest stocker on the market, with performance unknown since the demise of the lOOOcc Vincent in the 1950s.

But it was not until Harry Sturgeon replaced Turner as overall boss of the BSA Motorcycle

Division that the push started. It was instigated by news of Honda’s intention to market a 750, broken to a group managers’ meeting. Hele’s Triple project instantly achieved top priority, albeit as a stop-gap response to Honda.

During 1966, a 741cc P2 prototype featured a revised top end for improved cooling, with bore-and-stroke dimensions changed to 67 x 70mm, apparently to match other BSA/Triumph engines and simplify production. Geared primary drive was replaced by a quiet chain and the oil pump was relocated into the primary case. Dunlop came up with a tire to deal with the power-the K81, later called the TT100. Setting-up Triple production was a big job. Practically everything except the Triumph version’s frame and a few other parts was to be made at BSA’s Birmingham plant. Building distinct BSA and Triumph models further com-

plicated preparations for manufacture on aging machinery, although some costly new tooling was purchased.

Then, catastrophically, it was decided that the 750s should receive a styling job by Ogle Design, an automobile and industrial consultancy, which is how the infamous “breadbox” gas tanks and “raygun” mufflers were created.

When finally released in the fall of 1968, the Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket 3 had lost a possible three-year lead over Honda, whose 750 was being unveiled in Tokyo. And Ogle’s misguided attempt at styling held total U.S. Triple sales down to 7000 in the crucial 1969 season. A makeover for the Trident so it looked more like a Bonnie (and the pre-Ogle prototypes) helped recover sales only slightly in 1970.

There was a gifted stylist at Triumph who would have made a nice job of the Trident-if he’d had the chance. He was Jack Wickes, who prior to his death in 1997, recalled being sidelined during the buildup to Triple production. The 750 project’s twinmarque nature probably made it inevitable that the cosmetic work would go to a neutral third party. For although BSA and Triumph

were theoretically parts of a cohesive BSA Group, in reality the inter-factory rivalry was fierce.

The selection of Ogle Design was understandable. The firm’s work, such as shaping the Reliant Scimitar sports car, was generally admired as fresh and ultra-modern. But motorcycles are not automobiles, and BSA’s styling brief was inept, as exOgle staffman Jim

“We were told they wanted a flashy American look, like a Cadillac. We really let our hair down doing futuristic stuff. I never thought BSA would go for my flared silencer with three tailpipes. To be honest, as a motorcyclist, I thought the Triumph they brought in looked fine just as it was!”

Still in business, Ogle Design is unable to disclose the fee paid by the BSA Group, but it was obviously money that would have been better spent on quality control. And hastening the introduction of a five-speed, electric-start, disc-braked Triple.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue