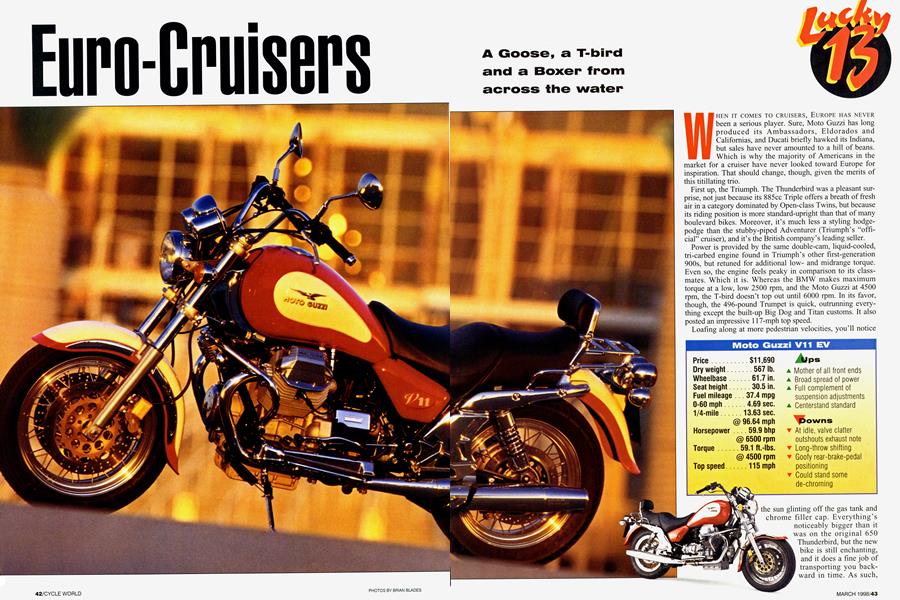

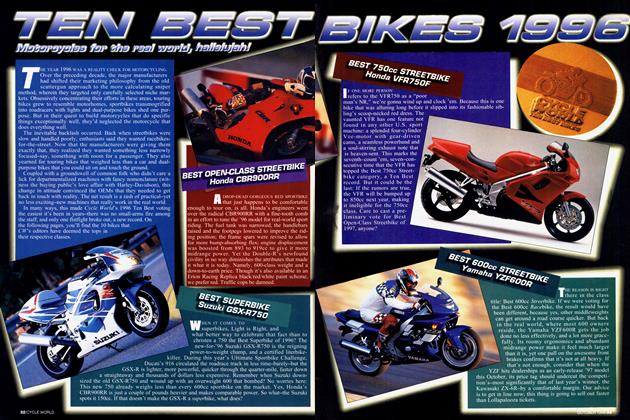

Euro-Cruisers

A Goose, a T-bird and a Boxer from across the water

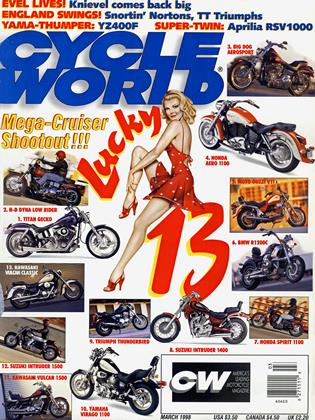

Lucky 13

WHEN IT COMES TO CRUISERS, EUROPE HAS NEVER been a serious player. Sure, Moto Guzzi has long produced its Ambassadors, Eldorados and Californias, and Ducati briefly hawked its Indiana, but sales have never amounted to a hill of beans. Which is why the majority of Americans in the market for a cruiser have never looked toward Europe for inspiration. That should change, though, given the merits of this titillating trio.

First up, the Triumph. The Thunderbird was a pleasant surprise, not just because its 885cc Triple offers a breath of fresh air in a category dominated by Open-class Twins, but because its riding position is more standard-upright than that of many boulevard bikes. Moreover, it’s much less a styling hodgepodge than the stubby-piped Adventurer (Triumph’s “official” cruiser), and it’s the British company’s leading seller.

Power is provided by the same double-cam, liquid-cooled, tri-carbed engine found in Triumph’s other first-generation 900s, but retuned for additional lowand midrange torque. Even so, the engine feels peaky in comparison to its classmates. Which it is. Whereas the BMW makes maximum torque at a low, low 2500 rpm, and the Moto Guzzi at 4500 rpm, the T-bird doesn’t top out until 6000 rpm. In its favor, though, the 496-pound Trumpet is quick, outrunning everything except the built-up Big Dog and Titan customs. It also posted an impressive 117-mph top speed.

Loafing along at more pedestrian velocities, you'll notice the sun glinting off the gas tank and chrome filler cap. Everything’s noticeably bigger than it was on the original 650 Thunderbird, but the new bike is still enchanting, and it does a fine job of transporting you backward in time. As such, even the conclusion from the yellowed pages of Cycle World's August, 1964, T-bird road test rings true here: “The seat, pegs and handlebars suit us perfectly, and everything operates with great ease and precision.” Well, almost everything. Carburetion is hugely flawed, with a pronounced hesitation right off idle. Shifts, at least on our low-mileage testbike, are painfully sticky. The solo-disc front brake is Sponge City, and the single-shock rear suspension is pretty harsh over the little stuff. There’s no arguing with the way the bike arcs smoothly through all manner of comers, though, or the uncanny consistency with which it draws enthusiastic Aokays from graying Baby Boomers at stoplights. Where the V11 really succeeds, though, is with its chassis. The massive Marzocchi fork and twin WP shock absorbers are damping-adjustable, a feature largely unheard-of on cruisers. > Effectively, you can tune the ride based on your personal preferences, just like on a sportbike. Planning a long freeway ride? Take out a little compression and rebound. Hitting

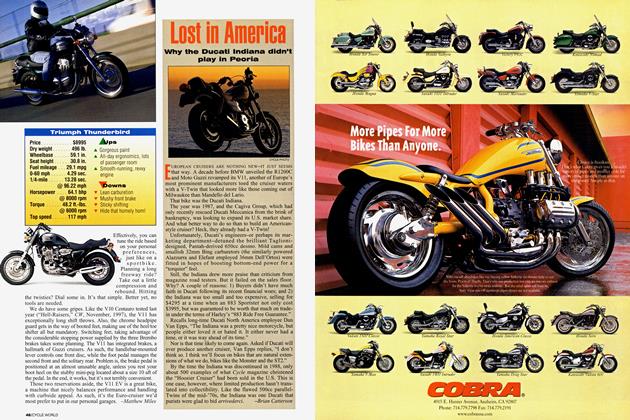

Moto Guzzi V11 EV

$11,690

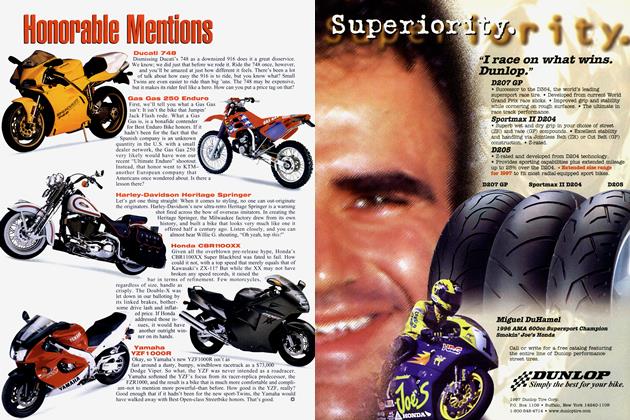

BMW R1200C

$14,290

You’ll get just as much attention on the BMW, particularly at gas stops and roadside diners. Bystanders fawn over the

R1200C’s polished-aluminum front swingarm, pinstriped gas tank and jutting chromecapped cylinder heads. “That’s the most beautiful bike I’ve ever seen,” allowed one slackjawed admirer. Not all agree. “Bland, bland, bland-a twowheeled VW Beetle, only not as stylish,” penciled one tester.

Styling criticisms aside, all agree the bike is magnificently detailed, right down to its leather-wrapped handgrips. Just try to find an errant wire, or an unattended cable. Other latemodel Boxer Twins should receive the same attention to detail. Cheers also to the hardstopping triple-disc Brembo brakes, the innovative flip-up backrest and the precise steering imparted by the choppedout Telelever front end. Also noteworthy is how little chassis jacking there is from the monoarm driveshaft.

Making the leap to cruiser duty, BMW’s latest-generation air/oil-cooled flat-Twin was bored, stroked, re-cammed and fitted with smaller-diameter valves. Intake area was reduced, as well, and the fuel-injection butterflies were trimmed down to make room for an automatic choke. Crack open the light-effort throttle, and the bike lunges forward with a tenacity previously reserved for modified Harleys. (Some testers considered this immediacy a negative, because it necessitates more precise throttle inputs to avoid the herky-jerkies.) Short-shifting is advised because, as our dyno numbers indicate, there’s nothing to be gained by revving the 1170cc engine beyond, say, 4500 rpm. Another reason is pesky vibration, noticed mostly at highway speeds; other twin-cylinder Beemers buzz, this bike throbs.

Then, there’s the admission price. Getting into BMW’s cruiser club (no, you don’t get to meet Pierce Brosnan) is expensive. Opt for ABS, as fitted to our testbike, and you’ll have to cough up $14,290. Like we said, pricey.

Costing some $2600 less is Moto Guzzi’s VI1 EV, formerly known as the California III. This is the third Guzzi we’ve encountered in less than a year, and frankly, we can barely contain our enthusiasm. We’ve all admired the simplicity of Guzzis past, but were often put off by their relative crudeness. Now, it’s as if designers got a glimpse of their own mortality, and didn’t like what they saw. Whatever the explanation, we are enamored with the repercussions, this bike included.

What’s most important here is that the Vll’s La-Z-Boy cruiser styling doesn’t impede on its ability to function as a real-world, everyday motorcycle. It’s got a comfortable, nearly upright seating position, exceptional cornering clearance (for a cruiser) and a smooth-running, fuel-injected 90degree V-Twin engine that revs to 8000 rpm. At stops, the longitudinally positioned crankshaft still causes the bike to rock from side to side when the throttle is whacked open (or closed), but it’s not as bothersome in this application as it is on, say, the Sport 1 lOOi.

Triumph Thunderbird

$8995

the twisties? Dial some in. It’s that simple. Better yet, no tools are needed.

We do have some gripes. Like the VIO Centauro tested last year (“Hell-Raisers,” CW, November, 1997), the VI1 has exceptionally long shift throws. Also, the chrome headpipe guard gets in the way of booted feet, making use of the heel/toe shifter all but mandatory. Switching feet, taking advantage of the considerable stopping power supplied by the three Brembo brakes takes some planning. The VI1 has integrated brakes, a hallmark of Guzzi cruisers. As such, the handlebar-mounted lever controls one front disc, while the foot pedal manages the second front and the solitary rear. Problem is, the brake pedal is positioned at an almost unusable angle, unless you rest your boot heel on the stubby mini-peg located about a size 10 aft of the pedal. In the end, it works, but it’s not terribly convenient.

Those two reservations aside, the VI1 EV is a great bike, a machine that nicely balances performance and handling with curbside appeal. As such, it’s the Euro-cruiser we’d most prefer to put in our personal garages. -Matthew Miles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

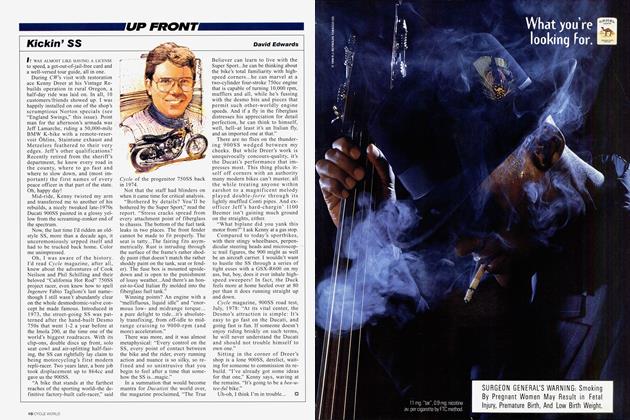

Up FrontKickin' Ss

March 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWinter Storage

March 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

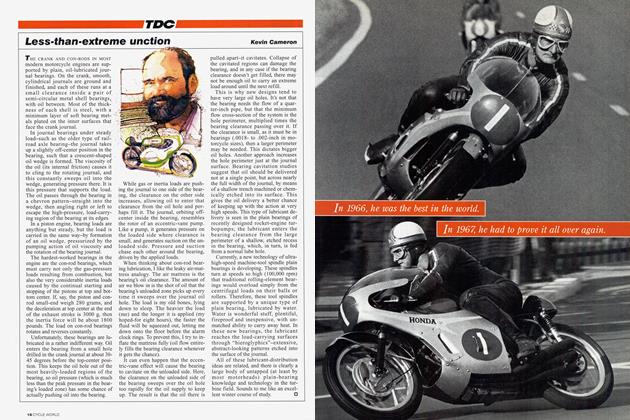

TDCLess-Than-Extreme Unction

March 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupIntercepted: Honda Vfr800 Impressions From Europe

March 1998 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBikes A Go At the Guggenheim

March 1998