BACK IN THE FRAY

RACE WATCH

Rediscovering AMA 250cc Grand Prix racing

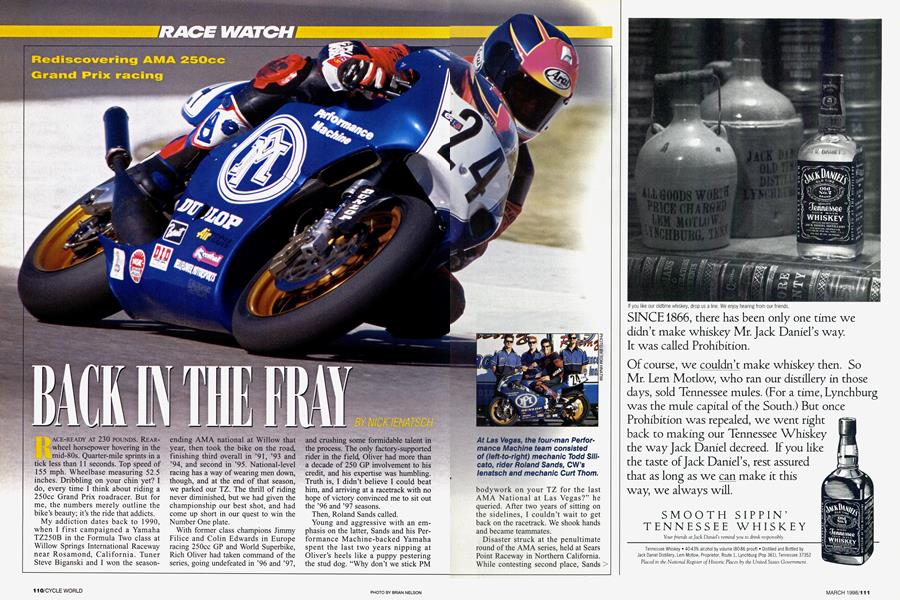

RACE-READY AT 230 POUNDS. REARwheel horsepower hovering in the mid-80s. Quarter-mile sprints in a tick less than 11 seconds. Top speed of 155 mph. Wheelbase measuring 52.5 inches. Dribbling on your chin yet? I do, every time I think about riding a 250cc Grand Prix roadracer. But for me, the numbers merely outline the bike’s beauty; it’s the ride that addicts.

My addiction dates back to 1990, when I first campaigned a Yamaha TZ250B in the Formula Two class at Willow Springs International Raceway near Rosamond, California. Tuner Steve Biganski and I won the season-

ending AMA national at Willow that year, then took the bike on the road, finishing third overall in ’91, ’93 and ’94, and second in ’95. National-level racing has a way of wearing men down, though, and at the end of that season, we parked our TZ. The thrill of riding never diminished, but we had given the championship our best shot, and had come up short in our quest to win the Number One plate.

With former class champions Jimmy Filice and Colin Edwards in Europe racing 250cc GP and World Superbike, Rich Oliver had taken command of the series, going undefeated in ’96 and ’97,

and crushing some formidable talent in the process. The only factory-supported rider in the field, Oliver had more than a decade of 250 GP involvement to his credit, and his expertise was humbling. Truth is, I didn’t believe I could beat him, and arriving at a racetrack with no hope of victory convinced me to sit out the ’96 and ’97 seasons.

Then, Roland Sands called.

Young and aggressive with an emphasis on the latter, Sands and his Performance Machine-backed Yamaha spent the last two years nipping at Oliver’s heels like a puppy pestering the stud dog. “Why don’t we stick PM bodywork on your TZ for the last AMA National at Las Vegas?” he queried. After two years of sitting on the sidelines, I couldn’t wait to get back on the racetrack. We shook hands and became teammates.

NICK IENATSCH

Disaster struck at the penultimate round of the AMA series, held at Sears Point Raceway in Northern California. While contesting second place, Sands > barged into fellow racer Randy Renfrow, who Sands said suddenly slowed. Both riders were injured in the subsequent crash, eliminating them from the Las Vegas finale. But rather than renege on his promise, Sands put me on his bike. I was excited to try a factory-kitted racer, as Sands’ TZ wears a special airbox, carburetors and cylinders. Things were lookin’ good!

Most racetracks run a promoter’s practice on the Thursday prior to an AMA national, and Team PM took advantage of the extra track time. I met mechanics Todd Silicato and Curt Thom, and went about the business of dialing-in suspension and breaking-in pistons. As more rubber was laid down on the track and grip improved. I began to experiment with different lines. Grand Prix roadracers are incredibly light and nimble, so I was able to use every inch of pavement to increase corner radius. More radius, more speed.

Then, I fell down. I had just passed another rider in Vegas’ tight, flat infield section. On the previous lap, I’d run right to the edge of the curbing on the first-gear double-left leading to a fast left-hander exiting the infield. “Next time,” I told myself, “I’m going to use the > curb.” Of course, I didn’t expect the concrete to be slippery. As soon as my front tire touched the freshly painted surface, I was on my butt. Since I’d botched my heat-race start, I did a couple of practice launches, using higher rpm. When the green flag waved signaling the start of the race, though, I overreved the engine and it went flat just as I fed in the clutch. Not a great start, > but not terrible, either. Then, all hell broke loose. And charge, I did. Initially, it was easy to pick off riders in clumps, but as I thrashed my way into the top 10, life got tougher. I got past Esser (again) and Michael Montoya, but the leaders were slipping away. My pitboard put me in eighth, with lap times varying from the low 1:40s to the high 1:41s, depending on traffic. Foster lost the front end in the same corner I had bobbled, moving me up another spot, which is where I finished, a couple of seconds behind sixth-placed Keith. Sorensen had dipped into the 1:39s to finish a lonely second to Oliver, but the group battling for third had given the crowd a real show. Matt Wait ended his season with a well-deserved third ahead of Moto Liberty teammates Takahito Mori and Toshiyuki Hamaguchi, all three on Honda RS250s. The bitterest pill for the PM team to swallow was that, had I not run off the track, we might have made the podium.

Prior to crashing, I’d turned a 1-minute, 43-second lap time. Unfortunately, I couldn’t back it up during official practice on Friday morning, my best time being a 1:44. The bike felt as if it were pivoting around the front tire entering corners, loading the front end and leaving the back end light. I wasn’t comfortable, and was still 3 to 4 seconds per lap slower than the leaders. Back in the pits, we firmed up the front and dropped the back, hoping to transfer some weight to the rear. A 250 never sits unmolested, and ours came apart between practice sessions on Friday, then again that evening.

Saturday’s heat races determined Sunday’s starting order. I was gridded on the last row of the second heat, and spent five laps chasing Chuck Sorensen, Mark Foster and Bobby Keith. Our chassis changes paid off, though, as my lap times dropped into the low 1:40s, and fourth place in the slower of the two races put me on the outside of the second row for the main event.

Sweeping through Turn 1, a lefthander that opens onto a long fifthgear straight, I picked off four or five riders, putting me 10th or 11th. The straight ends in a first-gear, 200-degree left that requires extremely hard braking, and it was there that my race almost ended. I slipped past Greg Esser, squeezed on the brakes...and simply didn’t get the bike slowed sufficiently to make the corner. I slipped and slid across the pavement like an elephant on ice, barely avoiding the other riders, and found myself headed toward the haybales, out of control. I stood on the rear brake, and the bike slid sideways, missing the bales by a couple of inches. Back under control, I re-entered the track in last place. At that point, all bets were off. I had to charge.

Some may feel that seventh is a commendable result. Well, we had higher expectations. Unfortunately, expectations don’t count for squat. You’ve got to perform on Sunday, when it counts. Asked what happened in Turn 2, I simply referred to four-time 500cc World Champion Eddie Lawson, who once told me, “Never make excuses, just do better next time.”

For those involved in AMA 250cc GP racing, there’s electricity in the air. Oliver has signed with Yamaha to campaign a YZF750-based Superbike. He brought professionalism and respect to the class, but his abilities as a rider and tuner put him in a category apart from everyone else. Now, his former competitors can grid knowing victory is at least conceivable.

The final race of the ’97 AMA season was an opportunity for me to rediscover a motorcycle that allows its rider to test his limits, not those of DOT-approved tires or a heavy streetbike-derived chassis. It hooked me once, and, who knows, I may have another crack at the class in ’98. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

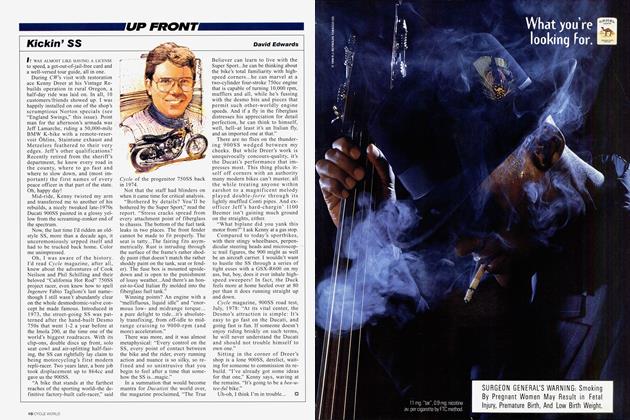

Up FrontKickin' Ss

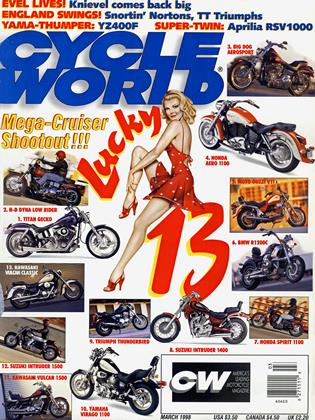

March 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWinter Storage

March 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

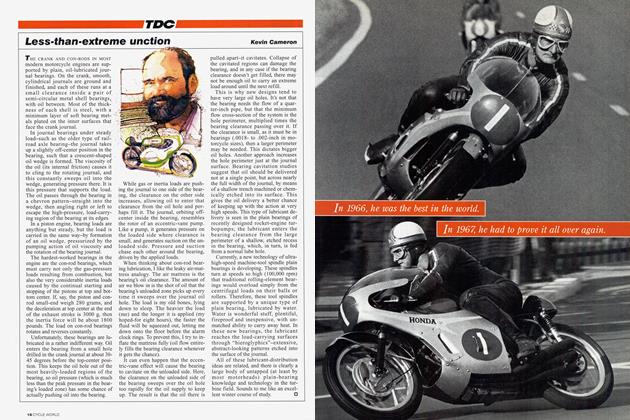

TDCLess-Than-Extreme Unction

March 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1998 -

Roundup

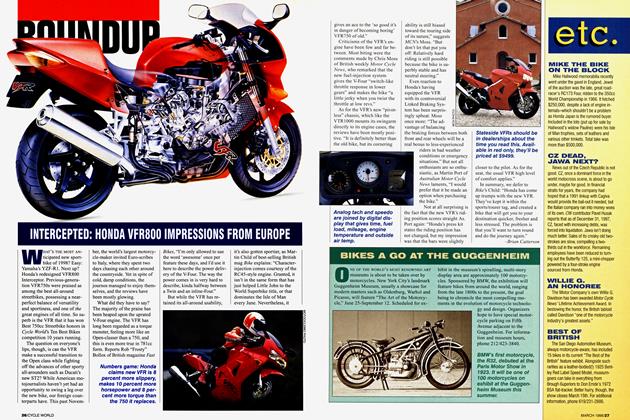

RoundupIntercepted: Honda Vfr800 Impressions From Europe

March 1998 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBikes A Go At the Guggenheim

March 1998