Development power

TDC

Kevin Cameron

IT'S ALWAYS FUN TO DEBATE WHETHER 'TIS nobler in the mind to use inverted-bucket tappets or to endure the outrageous slings and arrows of rocker arms. Advanced design features are, however, just an unproven bucket of bolts until development makes it all work as it should. Here is an example:

During World War II, no aircraft engine whose design was begun during thewar found any significant use in that conflict. The engines that did the wartime job were already in existence at the beginning of hostilities, and were pushed to higher power levels by constant development.

Today, 50 years later, mechanical systems remain extremely difficult to optimize and make reliable. Despite computer-modeling, improved materials and all the other advances that have occurred, engine development still requires cycles of testing to destruction, detail redesign and retesting until the desired performance and reliability are obtained.

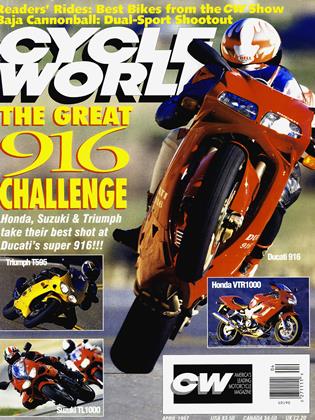

This makes Ducati look very sensible in making year-by-year updates to its basic 851 design of 1985, while others, replacing entire engine designs every three years or so, may be abandoning their children before they are fullgrown. The others are trying, with the aid of all the most sophisticated methods, to make their machines into winners (in one sense or another) straight off the drawing board, and modern engineering encourages us to believe this is possible. Computer models give us the power to design around troublesome things like crankshaft torsional vibration, con-rod bolt failure, etc.

We know that despite this, modern sports/racing engines continue to have traditional troubles (like camdrive failure) during development. Computer models are not yet able to erase all problems before they occur. Experienced human engineers must then let the engine tell them what it wants-that is, read the evidence in the failures, understand the failures, then redesign around them.

Maybe what I'm saying here is irrelevant beside the reasonable assertion that manufacturers design their machines not to win races or set records for durability, but to sell in the showroom. To thrive in the marketplace, conventional wisdom asserts, motorcycles must instantly implement the latest buzz-acronyms in metal-ATAC, EXUP, whatever techno-

logical pot-banging it takes to get market attention. All this demands (ready for the buzz-phrase?) "compression of the product-development cycle."

Henry Royce said, "I invent nothing. Inventors go broke." The strength of Rolls-Royce in building aircraft piston engines was its development department. Royce's designers were not innovators but developers, and they did it brilliantly-not designing so much as evolving an engine, as if it were a living organism responding to a harsh environment. Time and again, a small, intelligent change to the shape of a hardpressed piston, con-rod or crankcase greatly increased its durability. That's development. They used the engine itself as a model. Call it the exact logic of steel and aluminum, contrasted with the approximate logic of silicon-today's computer-modeling.

The production of technical novelties as a marketing tool forces breakthroughs to be scheduled. While Ducati uses development in the old way, to build the strength of one basic design, the new philosophy tempts others to leap straight from generation to generation of machine. A brand-new design attempts to make every element good right from the start. Development keeps what is proven in an existing design, and fixes what is unsatisfactory. Which task is more likely to succeed?

"Ah yes," says the modern engineer, "history makes good reading, but today product cycles must be compressed or you miss the boat, sales-wise. That means simultaneous engineering with

computer-modeling, concept to showroom in one giant, simulated, optimized, perfectly accurate, money-saving leap."

This is a beautiful ideal, and may work in the consumer-electronics industry or in econobox auto engineering. But where state-of-the-art mechanical systems are concerned, too little is perfectly known, so computer-modeling is harder to do and less accurate. Look at the troubles with the latest World Superbike 750 Fours: Despite application of all the big guns of modern engineering, these designs had lackluster first seasons.

Although marketing insists that new model must be piled upon new model to keep sales healthy, demand for the children of Ducati's long-developed 851 remains high. Is it possible that this highly developed machine has (dare I say it) classic appeal? With all the miracles of marketing, there's still no such thing as an instant classic. That status has to be earned, which takes time and trial by fire. Compressed product development leaves no time.

The purpose of development used to be clear: to produce a more reliable, more capable product. Today, that purpose is no longer so clear because the needs of marketing have become so desperate. Now, development gives us many things that are merely new, not necessarily better-or indeed even of any value at all.

Ducati has shown an alternative that works: capable classic status instead of a new model every five minutes, and long-term performance development instead of starting over before the previous design has matured. The constant rush of new models is motivated by an unexamined assumption: that motorcycles are commodities like consumer electronics-whoever is first to market with a shiny new gadget will win the pot. This ignores the special status a long-running model can earn through time and development.

Confusing development with marketing stops good engineers from perfecting their work. It brings technically advanced but immature products to market. Ducati is doing us and the free market a favor by taking its alternative route, reminding us all of the value of continuing development. It's also showing that motorcycles need not be commoditized, that classic status can work even for a modern sporting motorcycle. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Oakland Rodders

April 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCheesy Circumstances

April 1997 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1997 -

Roundup

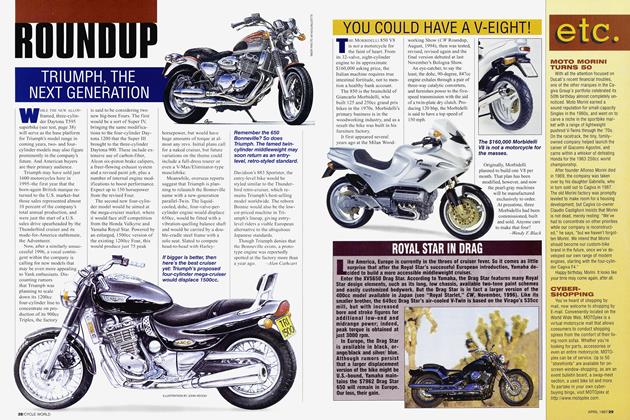

RoundupTriumph, the Next Generation

April 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupYou Could Have A V-Eight!

April 1997 By Wendy F. Black -

Roundup

RoundupRoyal Star In Drag

April 1997