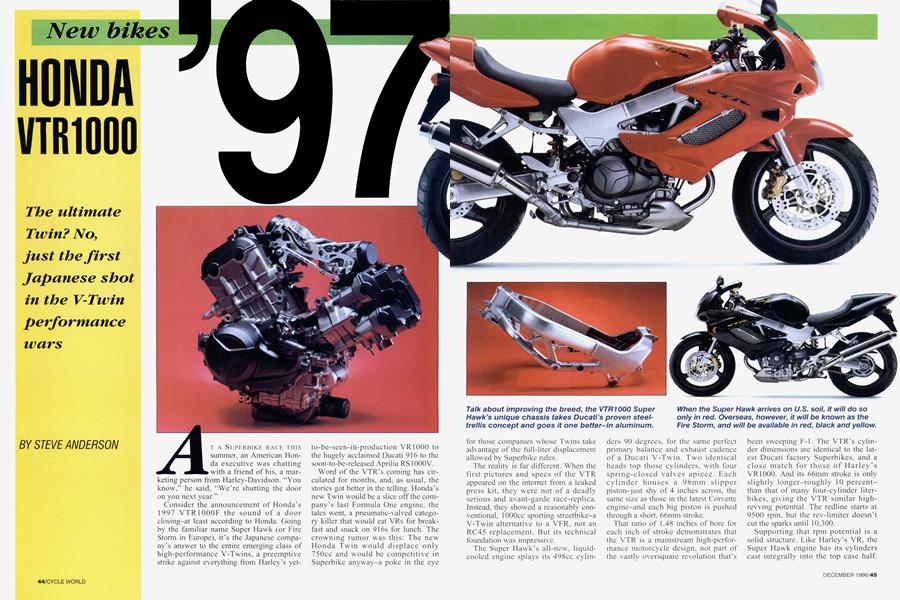

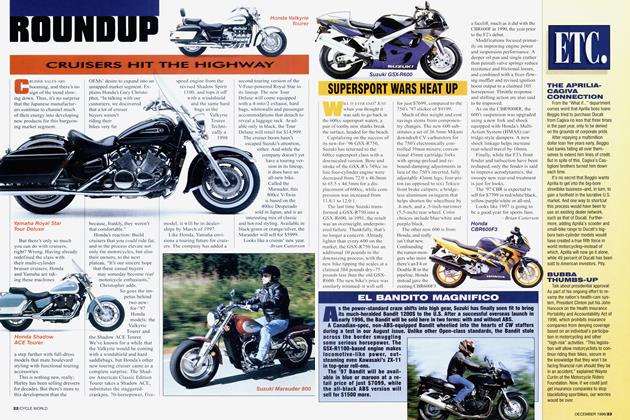

HONDA VTR1000

New bikes '97

The ultimate Twin? No, just the first Japanese shot in the V-Twin performance wars

STEVE ANDERSON

AT A SUPERBIKE RACE THIS summer, an American Honda executive was chatting with a friend of his, a marketing person from Harley-Davidson. “You know,” he said, “We’re shutting the door on you next year.”

Consider the announcement of Honda’s 1997 VTR1000F the sound of a door closing-at least according to Honda. Going by the familiar name Super Hawk (or Fire Storm in Europe), it’s the Japanese company’s answer to the entire emerging class of high-performance V-Twins, a preemptive strike against everything from Harley’s yet-

to-be-seen-in-production VR1000 to the hugely acclaimed Ducati 916 to the soon-to-be-released Aprilia RS 1000V.

Word of the VTR’s coming has circulated for months, and, as usual, the stories got better in the telling. Honda’s new Twin would be a slice off the company’s last Formula One engine, the tales went, a pneumatic-valved category killer that would eat VRs for breakfast and snack on 916s for lunch. The crowning rumor was this: The new Honda Twin would displace only 750cc and would be competitive in Superbike anyway-a poke in the eye for those companies whose Twins take advantage of the full-liter displacement allowed by Superbike rules.

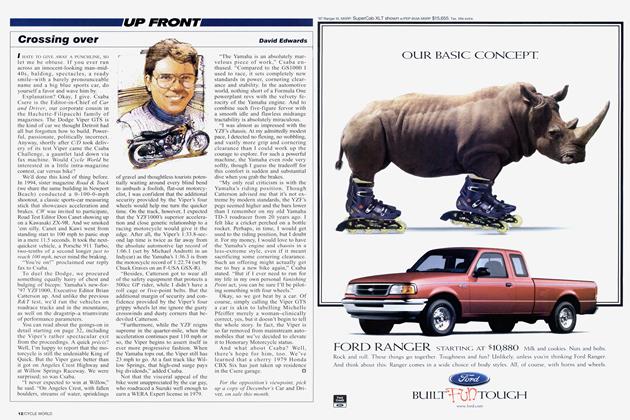

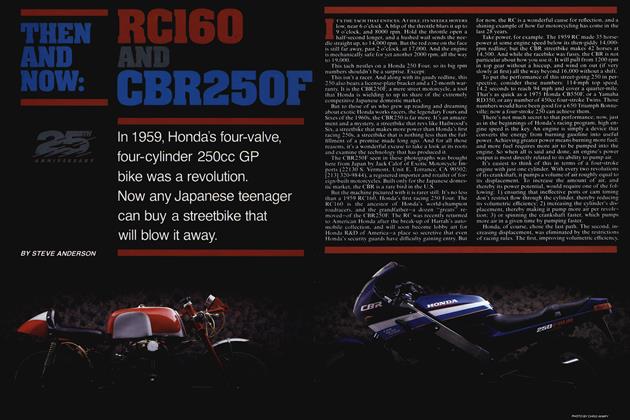

The reality is far different. When the first pictures and specs of the VTR appeared on the internet from a leaked press kit, they were not of a deadly serious and avant-garde race-replica. Instead, they showed a reasonably conventional, lOOOcc sporting streetbike-a V-Twin alternative to a VFR, not an RC45 replacement. But its technical foundation was impressive.

The Super Hawk’s all-new, liquidcooled engine splays its 498cc cylin-

ders 90 degrees, for the same perfect primary balance and exhaust cadence of a Ducati V-Twin. Two identical heads top those cylinders, with four spring-closed valves apiece. Each cylinder houses a 98mm slipper piston-just shy of 4 inches across, the same size as those in the latest Corvette engine-and each big piston is pushed through a short, 66mm stroke.

That ratio of 1.48 inches of bore for each inch of stroke demonstrates that the VTR is a mainstream high-performance motorcycle design, not part of the vastly oversquare revolution that’s

been sweeping F-l. The VTR’s cylinder dimensions are identical to the latest Ducati factory Superbikes, and a close match for those of Harley’s VR1000. And its 66mm stroke is only slightly longer-roughly IO percentthan that of many four-cylinder literbikes, giving the VTR similar highrevving potential. The redline starts at 9500 rpm, but the rev-limiter doesn’t cut the sparks until 10,300.

Supporting that rpm potential is a solid structure. Like Harley’s VR, the Super Hawk engine has its cylinders cast integrally into the top case half. This significantly strengthens the engine, allowing it to be light-just 150 pounds, compared to 156 for a Ducati 916, already a light Twin, and one not known for the strength of its crankcases. The VTR’s crank and rods run on plain bearings, like most modern fourcylinders, and power flows back to a massive, 10-plate clutch and a sixspeed gearbox.

A quick look at the VTR’s transmission ratios suggest they were chosen in part to solve one of a big Twin’s biggest problems: passing ride-by sound standards, tests performed by twisting the throttle fully open from a set speed in second gear. The top five gears are quite close together, with the jump between first and second gear very large-all the better to lower rpm, acceleration and noise in second gear during the prescribed test. Addressing the same issue are a big, 8-liter airbox, and the twin 4.5-liter mufflers. Big cylinders take big noisy breaths, and engineers can either hobble them with

small mufflers and airboxes, or silence them efficiently with big, complex and non-restrictive intake and exhaust systems such as these. Further aiding deep breathing are 48mm CV carburetors, among the largest on any motorcycle.

All impressive technology, but according to American Honda spokesman Dirk Vandenberg, high peak power wasn’t the goal of the VTR design team: “This isn’t a racing platform. We wanted big midrange.” Hinting at that is the 9.4:1 compression ratio, seemingly low for such an otherwise aggressive powerplant. That’s likely because cam timing is slightly on the short side, and intake and exhaust tuning is set to emphasize lowand midrange power-both factors that increase cylinder filling at low speeds, and thus require dropping compression to avoid excessive cranking pressures and detonation.

Honda claims 106 horses at the crankshaft for the Super Hawk, which should translate into the low 90s at the rear wheel. That’s shy of Ducati 916 figures, but up on every other current production Twin. More impressively, the claimed torque peak at 7000 rpm would translate into 79 rear-wheel horsepower at that speed-a truly impressive upper midrange if it’s duplicated on the Cycle World dyno by a production machine.

According to Vandenberg, the 916 wasn’t the original target for the big Hawk; instead, it was Ducati’s 900SS. Only later, when it was clear that the VTR’s performance would more closely match that of the 916, did Honda switch to the higher-end Duck for benchmark testing. In either case, Honda certainly borrowed generously from Ducati design elements, including attaching the swingarm directly to the crankcase and reducing the main frame to a truss tying engine to steering head. Of course, the Honda’s frame is executed in aluminum instead of Ducati’s tubular steel, and is very light at just 15.4 pounds. The light engine and the light frame keep dry weight down to a claimed 423 pounds, though a fully fueled and road-ready machine will likely weigh at least 10 percent more-or about the same as a 916-when it leaves Japan and arrives in the stronger American gravitational field.

The VTR’s riding position is somewhere between that of a CBR900RR and a VFR750 in raciness. Its bars are low, but the relatively short and narrow tank leaves the machine feeling far less bulky than the fat-tanked CBR900. The three-quarter fairing was designed more for rider protection than the ultimate in low drag, and funnels cool,

non-pressurized air to the airbox entrance and through twin side-mounted radiators-the latter a feature first seen on Honda’s NR500 four-stroke GP experiment.

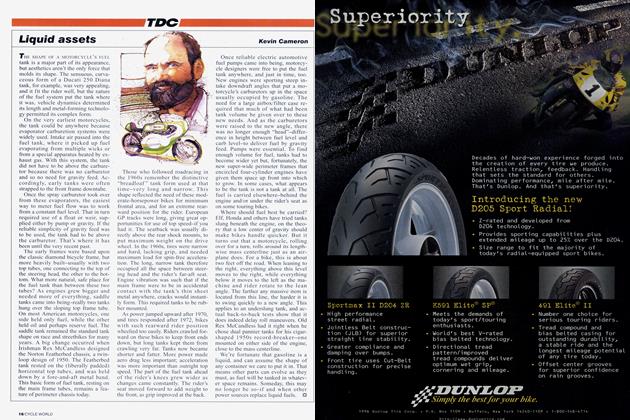

In the end, though, the VTR seems less like a bold Honda forward leap than a cloned and improved Ducati. There are just too many Italian design features on the machine, from the chassis arrangement-not shared with any other big Honda streetbike-to the exact shape of the mufflers to the monochromatic red paint, the only U.S. color available in the first year. When it arrives in the late spring of ‘97, however, the VTR should make life tough on the Italian com pany, offering near-916 performance for a less-than-900SS price-about $9100 according to early Honda projections.

But will it actually close doors?

Not likely. Ducati has been sitting on second-generation engines and new chassis designs for almost five years, awaiting the cash to produce them; that cash may finally have arrived. Harley continues to develop the VR1000 while regularly running ads for engine designers in trade journals; that cashrich company with its ties to the rapidly growing Buell operation is unlikely to give up plans to increase its presence in the sportbike market because of this machine. Instead, the Super Hawk will only raise the bar and set new standards for acceptable V-Twin performance and pricing.

But, of course, the VTR is only Honda’s first V-Twin shoe. Even as Vandenberg was explaining that the VTR wasn’t a racing platform, he also offered this: “We’re going to handle that. It’s just not ready yet...next year.”

end