SERVICE

Paul Dean

Reversal of Four-tune

Why do motorcycles with inline engines have the carburetors on the back of the motor and the exhaust pipes on the front? It would seem to make more sense to reverse them. Why not put the "the shortest distance between two points is a straight line" theory into use? Isn’t that the issue, to get fuel and air into and out of the combustion chambers as quickly as possible? It would make bikes less complicated to build and work on, and save a great deal of weight and space. With today’s “ram-air” intakes, this would seem to be an ideal solution to the big airboxes that take up so much space. Is this idea too good to be true? Chad Trent

Salem, Virginia

/n a word, yes. Exhaust pipes are on the front of the engine and carbs on the rear primarily because that arrangement has no real disadvantages, whereas reversing their locations offers numerous drawbacks.

First, remember that the design of inline engines has evolved from an earlier time in which virtually all motorcycles were air-cooled. Placing the hottest parts of the engine—the area around the exhaust ports—out front in the cooling airstream made perfect sense. Liquid-cooling has eliminated this concern on modern engines, but there are other reasons to keep the exhaust pipes where they are.

One is pipe length. Obviously, there is much less distance between the back side of the cylinders and the very' rear of the bike than there is between the front of the cylinders and the back of the bike. Cramming all the exhaust plumbing into that smaller space while also providing ample header length and muffler volume for optimum tuning-especially on an inline-Four—would create a design and manufacturing nightmare. It would also likely consume all of the space you might save by not having the airbox back there. On top of that, clustering all of the red-hot header pipes behind the cylinders would concentrate an enormous amount of exhaust heat in and around the cockpit area, particularly on bikes with full fairings. Keeping the rider from getting roasted like a Christmas goose would become a real engineering challenge.

Further, don't think of that “big airbox" as a bad thing; its large volume contributes mightily to a modern engine's wide, seamless powerband and low level of intake noise. If the airbox had to be at the front of the engine, its considerable size would compromise other critically important design elements, perhaps forcing the need for a longer-than-ideal wheelbase and preventing the engine from being located as far forward as possible for the best sport handling. And if the airbox were greatly reduced in size or eliminated altogether, engine performance would no doubt suffer in some way.

Also consider that the trend in highperformance engines is toward intake tracts that route mixture into the combustion chambers in as straight a line as possible. This calls for the cylinders to be canted forward and the carburetors to be aimed upward rather than to the rear. If the pipe and curb locations were reversed, the cylinders would have to be angled rearward, which would shift the overall weight bias too far to the rear; there also would be even less room behind the cylinders for the exhaust system, and less area between the front of the cylinders and the steering head for placement of the carburetors and airbox.

Then there s the matter of appearance. On unfaired, quarter-faired or half-faired bikes with inline motors, the bank of exhaust pipes sweeping down the front of the engine is a key part of the styling package. Somehow, sticking a clunky airbox or a row of carburetors on the front would ruin the mood, don't vou think?

Carb-cleaning magic

An off-idle stumble from stoplights on my 1984 V65 Magna prompted a visit to the local Honda dealer and an expensive prognosis: carb overhaul, worth $250 plus parts, which could easily run over the $300 mark. So, for a few bucks, I bought a bottle of automotive fuel-injector cleaner, called “Techron,” at a local Chevron gas station. Following the directions on the bottle, I dumped the entire 12 ounces into approximately five gallons of gas and ran it through the engine.

The results were phenomenal. The carbs are completely clean and the engine runs like new! Steve Brown Richardson, Texas

Thanks for the tip. Other major oil companies also make similar injector-cleaning additives, which produce comparable results.

Turbo tango

I own a 1985 Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo with a handling problem. I fully realize that this dated machine cannot handle on par with, or even remotely close to, modern sportbikes, but it has an oscillation that’s really disconcerting when I’m going around corners fast. I’ve tried to stop this wobble by replacing worn swingarm bushings and installing Dunlop K591 Elite SPs in place of mismatched tires. But the handling is still not at all what I think it should be. I need help in curing this problem, i.e. suspension settings, fork oil, etc., and also advice about any aftermarket products that may prove helpful, such as a steering damper. Any assistance you can offer will be much appreciated. Carman Pirie New Brunswick, Canada

Standard suspension settings for the 750 Turbo are as follows: 7.8 ounces of 10W30 engine oil (or J0W fork oil) in each leg; 5.7 to 8.9 psi air pressure in the fork (try 7.5 to 8 psi for hard riding); 0.5 to 43 psi air pressure in the rear shock (start with 30 to 35 psi for your needs); and shock rebound damping set on number 3 or 4 (of four possible positions).

Because of the age and likely high mileage of your bike, these settings might not solve the problem; the suspension may be badly worn-particularly the shock, which wasn’t an exceptional damper even when new. Also check the adjustment of the steering-head bearings to ensure that they are neither too tight nor too loose, and that their races have not become deten ted (small indentations that cause resistance during slight side-to-side steering movements). And use any of several methods (a long straightedge, a piece of string or even just the eyeball method) to determine if the rear wheel is adjusted so it aims precisely at the front wheel. A problem in any of these areas can lead to a wobble.

Your tires also may be contributing to the symptoms. While the 59Is are much better all-out sport and racing tires than the stock Michelin A48/ M48 combination, the original-equipment tires worked rather well on the Kawasaki Turbo, since the bike was designed around them. The Dunlops have a different sidewall height, tread profile and carcass construction than the Michelins, so they impart different steering characteristics. Your Turbo may be reacting unfavorably to those differences, especially if the rest of the chassis is not up to snuff.

Consider switching to the Michelins that are recommended replacements for the OEM rubber: an A 49 up front in the original 110/90V18 size, and an M48E in the rear, also available in the original 130/80 VI8 size. A nd once you get the handling in the ballpark, an aftermarket steering damper would be a useful addition.

Slippery Duck

i really enjoy my ’94 Ducati M900 Monster except for the dry clutch. It’s hard to pull in, engages too close to the handlebar and sometimes slips. Any suggestions about how I can correct these problems? Tim Miller

Madison, Wisconsin

First, thoroughly bleed the clutch 's hydraulic system to ensure that it contains absolutely no air. Then put slippage worries out of your mind by installing a Kevlar graphite clutch pack from Barnett. It comes with stiffen springs, so if you 're worried about heavy lever pull, use just three of the Barnett springs in conjunction with three Stockers, or simply retain all six of the stock springs. And the point of clutch engagement is determined by an adjusting screw on the clutch lever. The screw is secured with epoxy at the factory, but you can simply chip away the epoxy and turn the screw until you obtain a better engagement point.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoin' the Wave

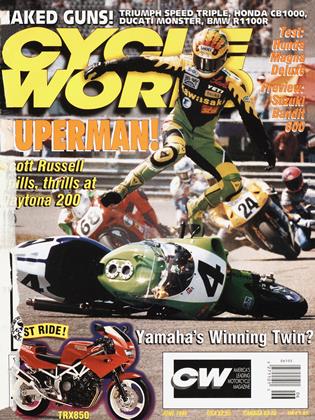

June 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDucks Unlimited

June 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAlloy Connection

June 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBandits Coming Soon To Your Neighborhood

June 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Surprise Single

June 1995 By Robert Hough