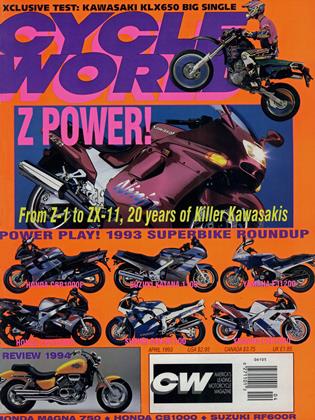

Z POWER!

TWENTY YEARS AGO, KAWASAKI DROPPED A BOMB CALLED THE Z-1

JOHN BURNS

BY NOW, EVERYBODY WHO cares knows that Honda built the first modern Four, and certainly the 1969 CB750 has earned its place in motorcycle history. But Kawasaki’s Z-1, introduced in 1973, was different. Call it the first modern superbike.

At a time of radical social change, that inaugural Z-bike made the CB look like Lawrence Welk. Beyond simply attracting buyers, the power-pumped Z-1 more nearly created its own religion. And while other manufacturers experimented with turbos, rotaries and V-Fours in the ensuing years, Kawasaki has always reserved a place in its lineup for a big-displacement, inline-Four rocketship that can trace its lineage back to the first Z as surely as the book of Genesis traces man back to Adam.

Z ONE AND ONLY

In 1972, Kawasaki’s H-l 500 and H2 750 two-stroke Triples held solid positions atop the performance-bike roost. Why fix what wasn’t broken?

For one thing, emissions regulations in the U.S. were strangling the life out of Detroit musclecars. Bikes weren’t yet affected, but as Bob Dylan said around that time, you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows. For another, the Triples had a foul reputation for handling. It wasn’t without good reason that the H-2 came equipped with two steering dampers.

Lots of torque and the desire for a wide powerband were other considerations that pointed toward large-displacement four-strokes. So while the Z-1 hit like a bolt of lightning, to Kawasaki it was simply the next logical step, and good business as usual.

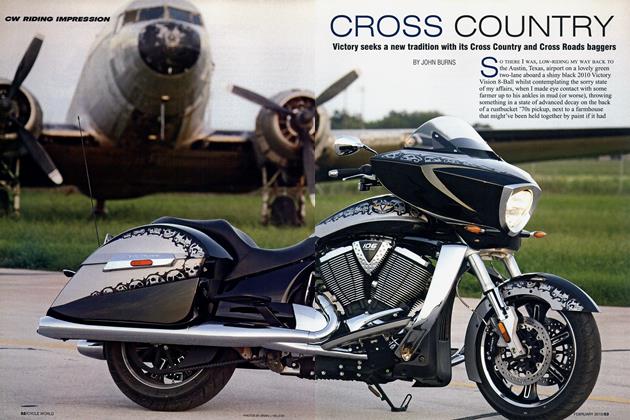

THF Z IN ANGER, PART 1

Not even Kawasaki had given much thought to roadracing the Z-1; it was thought of more as a big, civilized, understressed, all-around motorcycle-albeit a very fast one. Racing knowhow revolved around the lighter, two-stroke Triples, especially the H2-R racers as ridden by Yvon DuHamel, Paul Smart, Gary Nixon, Art Baumann, et al.

But the Triples’ days were numbered when Yamaha TZ700s began appearing on starting grids. Kawasaki couldn’t quite see the payoff in building that rvT 7TP OH/IQ ror»Q morrr Fortunately for the Z-1, along came production-based racing. The first

AMA-sanctioned race for production bikes happened at Laguna Seca in 1973. The rules allowed some engine modifications, but frames, wheels, exhausts, gearboxes and carburetors had to remain stock. Open Production racing was an immediate success, largely

because of the competitiveness of a wide variety of machinery-Reno Leoni Moto Guzzis, Butler & Smith BMWs, Ducatis. And Kawasaki was there from the start, Yvon DuHamel winning that

class was renamed “Superbike Production.” Engines were limited to lOOOcc, and there were other rules, most of which were ignored. Tech inspection, as one observer of the day noted, was to let you get an idea of how far behind you were in your cheating.

Packing 120-plus horsepower, with frames that had to approximate stock, these were machines that responded best to being yanked around by the scruffs of their necks via wide, dirtstyle handlebars. Just like Z-ls forced into the role of racer on the street, Z-1 s forced into the role of racer on the track bucked and weaved and slid. Steve McLaughlin, riding a Yoshimura Kawasaki at the ’77 Sears Point National, was doing well, a magazine report tells us, until “the activities of his Kawasaki caused his knees to knock off both outside sparkplug caps.”

Reg Pridmore won the first Superbike championship, on a BMW, but he’d seen the light; next year, he showed up on a Racecrafters Z-1 and won the ’77 championship. In ’78, Rego did it again.

Cycle World tested its first Z-1 in March, 1973. It ran a best quarter-

mile of 12.61 seconds at 105.63 mph to the H-2’s 12.83 at 99.55, all while running nearly twice as far on a gallon of gas-quietly, comfortably. Yours for $1895.

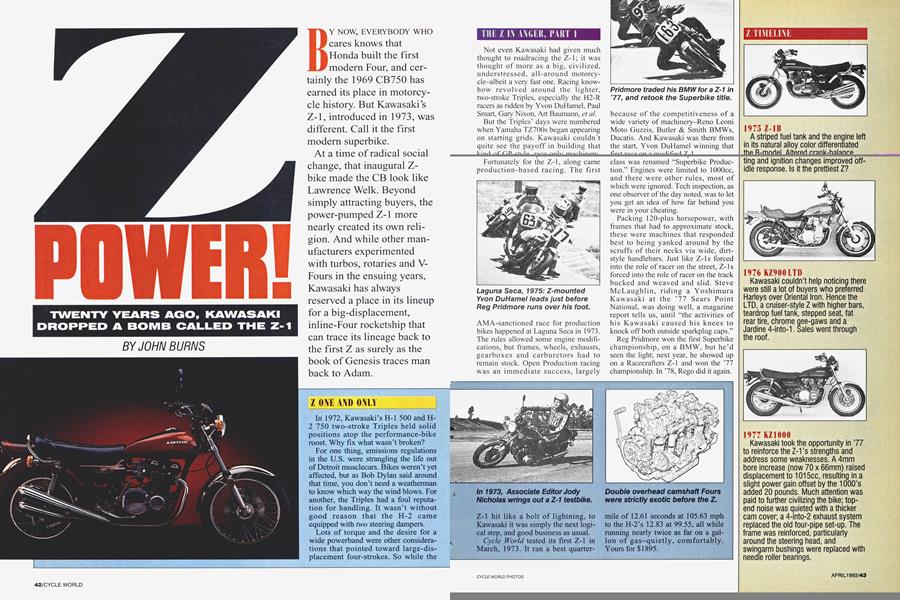

Z TIMELINE

1975 Z-1B

A striped fuel tank and the engine left in its natural alloy color differentiated thfi R-mnrlfll Alternd nrank-halanre ting and ignition changes improved offidle response. Is it the prettiest Z?

1976 KZ900LTD

Kawasaki couldn’t help noticing there were still a lot of buyers who preferred Harleys over Oriental Iron. Hence the LTD, a cruiser-style Z with higher bars, teardrop fuel tank, stepped seat, fat rear tire, chrome gee-gaws and a Jardine 4-into-1. Sales went through the roof.

1977 KZ1000

Kawasaki took the opportunity in 77 to reinforce the Z-1 ’s strengths and address some weaknesses. A 4mm bore increase (now 70 x 66mm) raised displacement to 1015cc, resulting in a slight power gain offset by the 1000’s added 20 pounds. Much attention was paid to further civilizing the bike; topend noise was quieted with a thicker cam cover; a 4-into-2 exhaust system replaced the old four-pipe set-up. The frame was reinforced, particularly around the steering head, and swingarm bushings were replaced with needle roller bearings.

1978 Z1-R

Kawasaki’s response to the café trend-started by the BMW R90S, John Player Norton, and H-D XLCR-was the Z1 -R. Except for 2mm-larger carburetors (a return to the 28mm units on the first Z-1) and a 4-into-1 pipe, Kawasaki said the R motor was same-same as the usual KZ unit. That didn’t stop Cycle magazine from screaming, “Motorcycling’s First 11-Second Quarter-Mile Stocker” on its cover. Theirs went 11.95 at 110.25 mph-a ringer, no doubt; ours only managed 12.48. Along with the pretty bikini-fairing, the R got the black-out treatment on everything, including its rear sprocket. Triple discs and cast wheels added to the overall weight, which was several pounds more than a standard KZ.

1981 KZ1000 CSR

Kawaphiles on a budget were offered the new KZ1000 CSR. Like the LTD, but with spoke wheels and tubetype tires, the CSR was bargain-priced at $3699—still almost twice the price of the first Z-1.

1982 KZ1000R1 ELR

In 1981, a young SoCal dirt-tracker named Eddie Lawson gave Kawasaki its first Superbike title, big horsepower courtesy of Rob Muzzy. Kawasaki celebrates that championship by building the KZ1000R1 Eddie Lawson Replica. Greener than green, mini-faired, growling through a Kerker 4-into-1, this one was hot-even though the engine was standard 1000J fare. Supposedly, 750 were built.

TURBO Zs

If the standard Z-1R was too slow for you, ex-Kawasaki exec Allen Masek put together a deal to build a limited number of Zl-R TC models; the TC standing for turbocharged. A Raj ay blower boosted the Z through the quarter in the high 10s, at around 130 per. Masek said he was going to build a thousand TCs...

And if that was too slow, Don Vesco set a new two-wheel land-

speed record at Bonneville in a streamliner powered by two turbocharged KZI000 motors (not far from stock), linked at both crank ends by toothed rubber belts, and driving through the

FALL FROM GRACE

Things got ugly in 1978. On three consecutive CW covers-February, March and April-three new Openclassers came pounding at Kawasaki’s door. Yamaha’s XS-11 blew the KZ1000 into the weeds, Suzuki’s GS1000 poured on the lighter fluid, and Honda’s six-cylinder CBX threw in the match, streaking through the quarter-mile in 11.64 seconds at 117.95 mph. Then as now, when the subject is Open-classers, the dragstrip is king, and never mind the “wellrounded” stuff; the KZ had become a performance pauper.

In 1979, you had your choice of three big Kawasakis. KZ1000: new, angular styling, seven-spoke cast wheels, auto cam-chain tensioner, 28mm CV carbs, $3399. KZ1000 LTD: the custom cruiser continues, $3699. KZ1000 ST: shaftdriven for the touring crowd, $3599.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan and Nancy moved into the White House, and there were five Zs: KZ1000, LTD, ST, Zl-R (back after a no-show in ’79), and the new KZ1000 G-l Classic-the industry’s

first fuel-injected bike. Looking much like the LTD, but in basic black and chrome, the Classic sold for $4199.

All the Zs got triple discs that year, and the switch was made to TCBI-transistor-controlled breakerless ignition. No more points.

RETURN TO POWER

1981 was a very good year at Kawasaki, a year in which it was obvious that the people in charge motorcycles a lot and intended to put the Z back on top.

For an appetizer, there was the KZ1000J, the third generation of the original Z, sort of, and the sportiest. Since tourers and cruisers now had the own Zs (the ST shaft and the there was no reason not to new J model. It was sleeved down to 69.4mm and 998cc (for racing purposes), and had its steering geometry tucked in to 27.5 degrees rake. Next came 34mm Mikunis, bigger valves, more cam and 9.2:1 compression. Now, it was a solid mid-11 -second sprinter, and the finished assembly came out light-lighter, even, than thencurrent 750s.

rear engine's gearbox. Vesco's amazing 318.598-mph record stood for 12 years.

THE Z IN ANGER, PART 2

The real Eddie Lawson Replica was somewhat rarer than the street ELR. Of the 30 KZlOOOSls supposed to have been produced for the ’82 season, four were bought by Kawasaki’s U.S. race team for Lawson and Wayne Rainey to ride. At $10,999 a pop, race director Gary Mathers said they were cheaper than building your own. Stock, Ed’s SI made 136 horses at the crank. Muzzy claimed 149, on the same dyno, when his work was done.

Despite being heavily outspent by Honda, despite Lawson missing two races (a slight case of a broken neck...), Eddie repeated as champion in ’82.

The AMA decided that for ’83, Superbikes would be 750cc: Sayonara Z-l. That didn’t stop Wayne Rainey’s underdog GPz750 from beating a slew of factory-backed Honda Interceptors.

But that wan’t enough to take back the quarter-mile crown, thanks to the Suzuki GS1100, so what the hell, Kawasaki sprang its red, fuelinjected GPz 1100, which promptly went out and tripped the lights at 11.18 seconds/119.1 mph. Largely based on the original Z motor, still air-cooled and still an eight-valver, the GPz displaced 1089cc via 72.5 x 66mm bore and stroke figures. Sixteen pounds heavier than the J model, a bit longer and more ponderous, about $600 dearer-all us magazine-purists preferred the J.

ALWAYS A TRETT

In 1983, drag racer Elmer Trett becomes the second man to break the 200-mph barrier, clocking 7.34 at 201.34 mph in front of 67,000 fans at Indianapolis on a supercharged Kawasaki. Trett continues to campaign a Z-l-based bike to this day. In fact, despite the advent of liquid-cooled engines and multi-valve cylinder heads, the old-fashioned Z-motor-as well as the air-cooled Suzuki GS mill-forms the mainstay of drag racing in the U.S.

1983 SPECTRE 1100

By 1983, the marketing people were getting worried as sales slumped. Then they remembered how many LTDs they’d sold, and in a failed bid to repeat history, the ugliest Z was born.

1984 NINJA 900

Nearly a decade after the first Z-1, in front of Big Brother and everybody, Kawasaki moved away from air-cooling and eight valves, and into modern times. With its all-new, 908cc, liquid-cooled 16valver tucked neatly within Kawasaki’s first full fairing, the Ninja 900 enters the almost-never land of 140-mph plus.

1985 ELIMINATOR 900

In 1985, it occurred to Kawasaki that many of us Americans were terminally interested in drag racing, and wouldn’t know a canyon if we fell into one. Hence the ZL900 Eliminator. This was a 908 Ninja motor tuned for lowand midrange whomp, rubber-mounted in a long, low chassis to combat the dreaded loop, with a fat, 15-inch rear tire. Requiring much less finesse off the line than the short, peaky Ninja, the Eliminator was immediately out to launch. A showroom flop, it was eliminated from the lineup after 1987.

1986 ZX1000R

Bored and stroked to 997cc, sporting Kawasaki’s first perimeter frame (steel), this tail-geared, stealth-black Ninja pushed the top-speed envelope very nearly to 160 mph.

1988 ZX-10

It’s a vicious circle. Just when we thought enough was enough, Yamaha sprang its FZR1000, Suzuki its big GSX-R. Does history give a clue as to Kawasaki’s next move?

It was the ZX-10. Through various refinements, Kawasaki extracted substantially more power from the ZX-R’s 997cc while making the engine lighter and quicker-revving, and stuffed it into an aluminum “E-box” frame. Naturally, it was the fastest thing on two wheels, if a bit heavier and not quite as sharphandling as the FZR and GSX-R, while retaining real-world conveniences like a centerstand and two-up cruising capability that the new repli-racers abandoned.

1990 ZX-11

Where’ve you been? Based on the ZX10, but with almost no interchangeable pieces, this 1052cc ram-inducted Suppository from Hell was the fastest, most powerful streetbike ever devised by man, capable of well over 170 mph as delivered. How can the police arrest what they can’t even see? This year, the ZX-11 was superseded by a new and improved ZX-11, the fastest, most powerful streetbike ever devised by man, capable of...well, you get the picture.

1993 ZR1100

Twenty years after unleashing the Z-1, Kawasaki comes full circle and brings us the ZR1100, a big, civilized, understressed, all-around motorcycle. It’s doubtful if lightning will strike twice, but the ZR is further proof that the retrostandard concept has legs.

TERMINATOR I

WERA’s new unlimited Formula USA class provided a forum in which the ZXIOOOR Ninja could speak its piece, and Earl Roloff’s “Terminator,” stripped down to about 450 pounds, but with stock engine and gearbox-or so Earl sayswon the first F-USA championship in ’86. This Lenin of winnin’ is now entombed in a glass case at Willow Springs Raceway.

THE ULTIMATE Z-1?

It’s 1992 and Steve Rice wins the Prostar Top Fuel/Funnybike championship on a turbocharged, fuel-injected, alcoholburning, 1260cc Kawasaki. Something in the neighborhood of 45 pounds turbo-boost allows the bike to put out around 425 horsepower. No big deal, really, until you consider Rice uses the stock crank, cylinder heads and cases from Kawasaki’s current police bike-an engine barely changed from the original Z-1.

Z END

What’s it all mean, then? Is The Big Kawasaki more or less important than the Beatles? Than Vietnam? The death of the USSR? Madonna and Sean Penn’s failed marriage?

In an era when we learned to distrust corporations, governments, spotted owls and our own hedonism, Kawasaki, like a black-sheep uncle, has never failed to pat us badboyishly on the head, give us a surreptitious snort from a hidden flask, and affirm our suspicion that life without suspense is no life at all, that the unexamined decreasingradius blind curve just might be the soonest path to introspection for people like us.

While some other manufacturers may have succumbed to hubris and the lockstep mentality that spawned EuroDisney and McRibs, Kawasaki has historically been first to thumb its corporate nose, fire up a new projectile, and send the poultry scurrying and clucking back to the coop. Caveat emptor this, Kawasaki says, gesturing rudely toward their skedaddling tailfeathers.

Cool, we say, but can’t you make it a little faster?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart