WHERE THERE'S A WILL

HANDICAPPED MOTORCYCLISTS FIND A WAY TO KEEP ON RIDING

JOHN DORRANCE

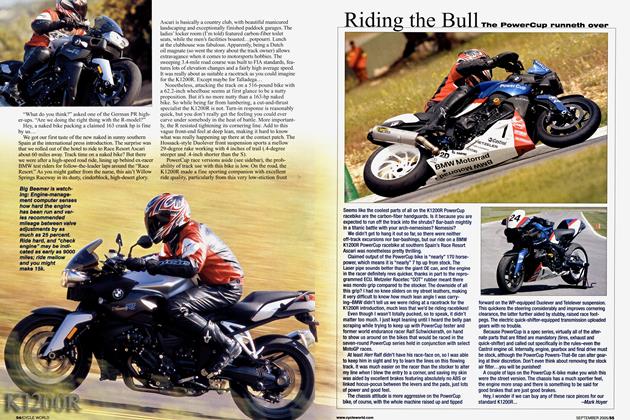

AT FIRST, SEEING THESE PEOPLE enjoying their motorcycles stretches our credulity. This can’t be right. These people are handicapped-some of them by accident, some of them by the cruelty and caprice of life itself. We may not express sympathy, but we damned sure feel it. And we don’t express relief that it’s them, and not us, but we damned sure feel that, too.

All of which is more than a little unfortunate, and more than a little uncalled for. Because motorcyclists are motorcyclists, and the level of enthusiasm handicapped riders exhibit, and the joy they derive from riding, is something we all can understand.

Take Bob Nevóla, for instance. A 35-year-old bartender at the Hard Rock Café in New York City, Nevóla belongs to a special minority. He is what many Americans call handi-

capped-or, in more politically correct language, physically challenged. Bom without part of his left arm and hand, Nevóla is also an avid motorcyclist whose current stable includes a Honda 650 Custom, a Honda 450 Nighthawk and a Kawasaki 750R Ninja, all converted to accommodate his needs.

“My whole life, I was always able to try something and accomplish it. As a teenager, I used to have dreams about motorcycling,” he says. One way or another. Nevóla was going to ride. He recalls that he coaxed his father into a motorcycle dealership with the hope of purchasing a floor model. “We were asking pretty sensible questions as to how I was going to ride it. The mechanic had no clue what to tell me. We left the shop and my dad said, ‘No way am I signing for a loan; you can’t even figure out how to work this bike.’ ”

Then Nevóla discovered the Honda 750 Hondamatic, factory-equipped with automatic transmission. The Hondamatic, built from 1976 to ’78, was meant to lure greenhorns, intimidated by manual shifting, into the sport. With no clutch to manipulate, a person could ride all day with only right-hand control. Not exactly an expert’s machine, but “it was a Godsend to a gimp rider like me,” says Nevóla.

"I'm a gimp... what medical science calls a paraplegic... I worked hard to get this way and deserve all the credit.” -Jeff Smith

Gross-country touring soon gave Nevóla the confidence to acquire a far less sedate machine, a Honda CB750F Super Sport, which he had to convert. He investigated various mechanical/electrical contraptions, and after a few weeks of work, he’d installed an integrated brake system, relocated critical switches and transplanted the clutch lever to the right side of the handlebars.

Along the way, Nevóla wondered if he was the only handicapped individual with a motorcycle and a craving for the open road. In 1986, he founded the National Handicapped Motorcyclist Association (32-04 83rd St., Jackson Heights, NY 11370) and published The Gimp Exchange, a newsletter that he hoped would provide a forum for handicapped riders.

Soon Nevóla was receiving much more mail than he could handle. Handicapped riders scattered across the U.S. were, just as Nevóla had been, starving for like-minded company and information. By the spring of 1990, Nevola’s sporadically published newsletter had 300 subscribers. He estimates about half the riders who receive The Gimp Exchange acquired their handicaps as a result of traffic accidents. The other half are handicapped because of other types of accidents, as a result of diseases such as arthritis and polio, or by birth defects. “There are thousands of stories out there,” he says.

One of the first stories Nevóla discovered was that of Jeff Smith. An Arizonian with a freely admitted obsession for highperformance bikes, Smith earns his living as a freelance journalist who writes mostly for alternative newspapers. To call Smith a free thinker would be akin to labeling Genghis Khan a passable military man.

Nevóla included one of Smith’s essays in an early newsletter. In it, Smith wrote, “I’m a gimp, by my own etymology. What medical science prefers to call a paraplegic. I got this way off the high side of a Ducati 900 Desmo SS, in an off-camber sweeper, in the woods, on a cold, wet October day, on the way to the Aspencade Rally in Ruidoso, New Mexico. This was no fluke of the sort that makes so many gimps bitter, ‘Whyme-Lord?’ human husks. I worked hard to get this way and deserve all the credit.”

Indeed, this was the second 100-mph-plus crash Smith had suffered in one year. As a club-level roadracer, he’d experienced a nasty spill that resulted in a full rack of broken ribs. So when he awoke in the hospital the second time, he quickly checked for damage.

“I wiggled my fingers,” recalls the 47year-old Smith. “I thought, ‘Okay, you’re a writer, your brain is apparently working, your fingers are working. You’re okay. You dodged the bullet.’ ” A few hours later, the surgeons informed him that he was permanently paralyzed from the chest down.

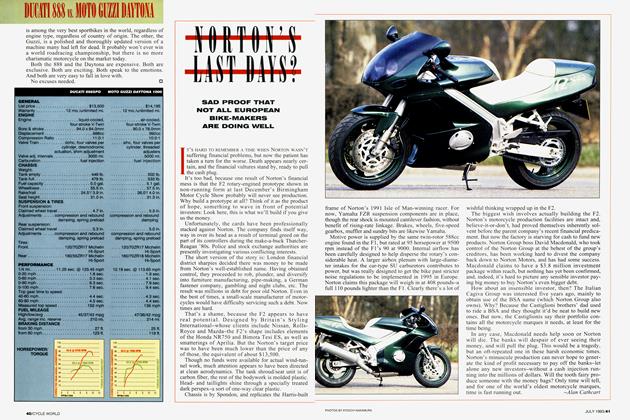

“Everybody says riding means freedom, but it means a little more to me than it does to most people... I’ve got to keep well if I’m going to ride, and riding keeps me well.” -Janice Browne

But Smith rebounded well. “It’s life. What are you going to do? Quit?” he asks rhetorically. “Hell, no. This is the best game in town.” Smith began his rehabilitation by putting together an old BMW sidecar rig operated by custom-designed hand controls. A year out of the hospital, he rolled his wheelchair into his local DMV ready to apply for a motorcycle endorsement on his driver’s license. He recalls, “The lady behind the counter took one look at me, and I could see the bureaucratic eyes glazing over.”

After a brief but thoroughly frustrating runaround, Smith decided to ride his new motorcycle assembly sans proper permits-a regular driver’s license would have to suffice.

“I swore to myself, to my wife and to everybody else that I was willing to slow down,” says the former speeddemon, “but soon I wanted more grunt and a little better aerodynamics.” And that’s why a sidecar-equipped BMW K100RS replaced the first rig, and why that was ultimately replaced by a more speedy BMW Kl hack.

“I get on the bike pretty much like mounting a horse. Then I fold the wheelchair up and set it between the motorcycle and the sidecar,” he explains. His right hand operates the throttle and brakes. A rocker switch linked to a magnetic solenoid allows him to shift with a strike of his left thumb. “You just hit up for an upshift and down for a downshift,” he explains, “I can shift faster than most guys

can shift with their feet.”

Smith admits that days on his bike don’t come easy anymore. “It hurts. My back aches, my shoulders ache, all the bones I broke hurt like hell. But you can figure out a way to do just about anything you damn well want to do. You just have to want to bad enough.”

Janice Browne would agree, although unlike Smith’s disability, hers wasn’t selfinflicted. Another subscriber to The Gimp Exchange, she informs people that “I don’t like to call myself handicapped. I prefer to call myself ‘bent.’”

Eight years ago, former rider Browne, a 43-yearold mother of five, developed psoriatic arthritis-a degenerative disease that often leads to a shortened life span for the stricken. “As I got older and as I got sicker, the challenge to ride again got stronger,” she explains. “I didn’t want to wait 10 years and say, ‘Gee, I should have ridden.’ ”

Browne experienced her first taste of motorcycling while attending a Philadelphia high school, tucked on the rear of her boyfriend’s bike. After moving to Lancaster, in the high desert of Southern California, Browne received a 125cc Honda from her Harley-mounted husband so they could go on weekend runs together. The responsibilities of being a parent soon mothballed her Honda, however. Also, she was spending a lot of her time nailing up sheet rock and installing electrical systems as part of the family’s homebuilding business.

Then she became ill.

“If my doctor had his way, I’d sit in a chair and watch the world go by. Because along with the arthritis, I have some heart problems, and I fight my blood pressure all the time,” Browne says. “I’ve gone to medical appointments on my bike in winter. I walk in and my doctor just shakes his head.”

Browne considers her three-wheeler, built from the remains of a Harley Sportster, a good form of therapy.

“Riding works my spirit. Everybody says it’s the freedom. But that means a little bit more to me than it does to most people: the freedom from a wheelchair, and from crutches, and from canes. I’ve got to keep well if I’m going to ride, and the riding keeps me well,” she says.

As president of Love and Lace, a women’s motorcycle club, Browne has logged 5000 miles in the last three years, riding to numerous get-togethers across the Western states. But advancing arthritis causes her joints to swell painfully, and it continues to weaken her limbs.

Browne’s husband built her trike with modified suspension to cushion her increasingly delicate spine. Leather-sensitive brakes respond to the small amount of pressure she’s still able to exert on the levers. Browne insists, “I will ride until I can no longer stop the bike.”

Browne had planned to test herself and her machine with a journey back East to visit her father. Now, she says, “My body isn’t going to allow me to go. That’s one of my dreams that I didn’t make. But there’s a lot more of my dreams I did make.”

Ken Hawkins also harbors a cross-country goal, but for him the final destination rests in South Dakota’s Badlands at Sturgis. Hawkins, a 49year-old microbiologist, became a paraplegic at age 16 after a deer-hunting accident. He’s a man who didn’t even consider motorcycling until decades after his injury.

“Em not one of those people who had an extreme desire to get back on a bike, because I’d never been there,” he says. “I didn’t even know I wanted to ride. I was busy playing mechanic. I like to build things.”

Hawkins works in California’s Silicon Valley, a high-tech accumulation of suburbs 40 miles southeast of San Francisco. During the day, the bearded scientist conducts tests for any infectious diseases that might be creeping into the region. But when he returns to his semi-automated house at twilight, he quickly rolls into his garage/machine shop, and that’s where his talents truly bloom.

It is here, among welding machines, drill presses and stacks of manuals, that he creates elevating-seat wheelchairs and mono-skis for the disabled. Engineering students from Stanford University often work with him to study his designs and to earn academic credits.

“I’d been looking at all types of lightweight vehicles to help move a wheelchair,” he explains of his involvement with motorcycles. One of Hawkins’ early conveyances linked a chainsaw motor to his chair. It lacked speed, to say nothing of its fickle stability. “If you’re going to go faster than 15 miles per hour,” he now notes,

“you need a machine that has bigger tires and wheels to handle the road.” Motorcycles seemed to be the perfect answer.

He purchased a used 1978 400cc Hondamatic and began tinkering in earnest, ending up with a pragmatic blend of Roman chariot and motorcycle.

To use the beast, Hawkins scoots his wheelchair directly into an open-ended, box-shaped sidecar created from tubing and plywood. The bike’s handlebar has been transferred to the front of the homemade chariot; a steering rod connects it to the Honda’s fork. A handoperated lever allows him to shift.

“It’s the most fun you can have sitting up,” the ever-smiling Hawkins says. “I can wheel up to the back of my bike, lock my chair on the platform, and take off almost as if I haven’t stopped rolling, almost that fast.”

He soon realized that riding had become, as he puts it, “One of the biggest things in my life,” so much so that his car usually stays at home in lieu of his unconventional three-wheeled transport. “There’s a feel of the wind in your face. It’s like therapy. I’ll get on my motorcycle in the summer and I’ll just start smiling. I’ve seen people almost get into accidents because they’re so busy watching me. I get a lot of thumbs-up,” he says.

If Hawkins’ contraption draws attention on the freeway, then his newest project is guaranteed to turn some heads. The assembly consists of two 400cc Hondamatics linked together on opposite sides of the platform that holds Hawkins and his chair. He’s presently testing the prototype with slow putts around his suburban block.

As soon as he irons out the kinks of simultaneous shifting-he’ll either use electromagnetic switches or mechanical linkages to solve this problem-Hawkins plans to hit the interstate for Sturgis and the annual gathering of Harleys.

Why?

“It just sounds like fun to go to a big biker party,” he says.

He adds that after 33 years of wheelchair confinement, one of his hips has seriously deteriorated. If the other hip goes bad, he won’t be able to stay upright for extended periods of time. “If I can’t sit up all day, I can’t make it to Sturgis. So I’m trying to get it done. There’s a time frame here. I can’t dally around my whole life.”

It’s just that sort of spirit that led Bob Nevóla to form the National Handicapped Motorcyclist Association and publish The Gimp Exchange.

“These people didn’t allow their injuries to stop them from living,” he says. “Besides, how can you call a person who rides crosscountry on a motorcycle handicapped? How can you say that? It just doesn’t work.” U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart