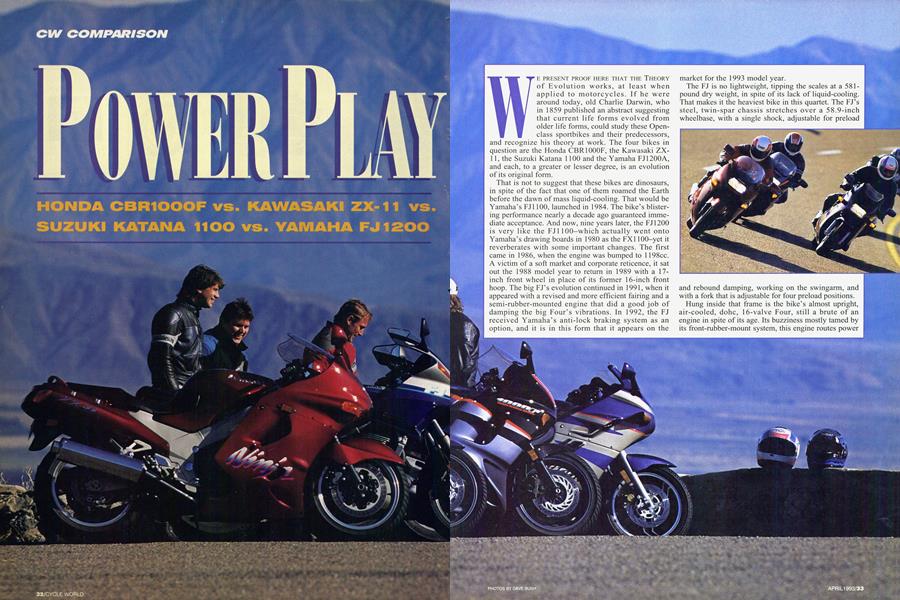

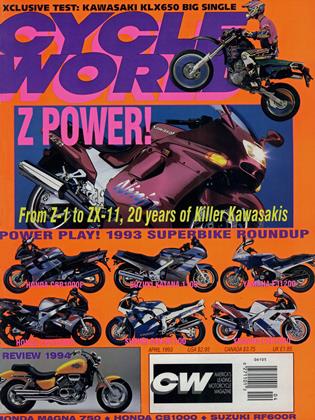

POWER PLAY

CW COMPARISON

HONDA CBR1000F vs. KAWASAKI ZX-11 vs. SUZUKI KATANA 1100 vs. YAMAHA FJ1200

WE PRESENT PROOF HERE THAT THE THEORY of Evolution works, at least when applied to motorcycles. If he were around today, old Charlie Darwin, who in 1859 published an abstract suggesting that current life forms evolved from older life forms, could study these Openclass sportbikes and their predecessors, and recognize his theory at work. The four bikes in question are the Honda CBR1000F, the Kawasaki ZX-11, the Suzuki Katana 1100 and the Yamaha FJ1200A, and each, to a greater or lesser degree, is an evolution of its original form.

That is not to suggest that these bikes are dinosaurs, in spite of the fact that one of them roamed the Earth before the dawn of mass liquid-cooling. That would be Yamaha’s FJ1100, launched in 1984. The bike’s blistering performance nearly a decade ago guaranteed immediate acceptance. And now, nine years later, the FJ1200 is very like the FJ1100-which actually went onto Yamaha’s drawing boards in 1980 as the FX1100-yet it reverberates with some important changes. The first came in 1986, when the engine was bumped to 1198cc. A victim of a soft market and corporate reticence, it sat out the 1988 model year to return in 1989 with a 17inch front wheel in place of its former 16-inch front hoop. The big FJ’s evolution continued in 1991, when it appeared with a revised and more efficient fairing and a semi-rubber-mounted engine that did a good job of damping the big Four’s vibrations. In 1992, the FJ received Yamaha’s anti-lock braking system as an option, and it is in this form that it appears on the

market for the 1993 model year.

The FJ is no lightweight, tipping the scales at a 581pound dry weight, in spite of its lack of liquid-cooling. That makes it the heaviest bike in this quartet. The FJ’s steel, twin-spar chassis stretches over a 58.9-inch wheelbase, with a single shock, adjustable for preload and rebound damping, working on the swingarm, and with a fork that is adjustable for four preload positions.

Hung inside that frame is the bike’s almost upright, air-cooled, dohc, 16-valve Four, still a brute of an engine in spite of its age. Its buzziness mostly tamed by its front-rubber-mount system, this engine routes power through a five-speed transmission-more than enough forward notches for this engine’s prodigious torque production.

With its minimalist lower fairing that shows off the bike’s handsome engine, the FJ12 is in some ways the most traditional and comfortable of this group, and that’s just one of the reasons it has enjoyed a long, happy life. Another reason is that when a rider whacks the bike’s four 36mm Mikunis open, he’s greeted with astounding acceleration: In the quartermile, the FJ turned in an 11.31-second showing, and recorded 140 mph on its top-speed runs-pretty impressive for an old dog.

If the FJ12 is the oldest bike in this group, the Kawasaki ZX-1 ID counters by being the newest. It is a considerable revision of the incredible, 176-mph ZX-11C introduced in 1990, which was a development of the ZX-10 first shown as a 1988 model, itself based on the 1986 Ninja 1000.

Though in some ways it is very like the ZX-1 lC-which remains in the lineup for ’93—this new incarnation of the biggest and baddest from Kawasaki also is very different. Weighing in at 560 pounds with an empty fuel tank, and riding on a 58.9-inch wheelbase, the ZX-1 ID is suspended by a shock and fork that each are adjustable for preload and rebound damping. Arching gracefully between those two sets of suspension components is a dual-spar frame built from sheet aluminum that’s stamped into shape and then welded together. This new frame is claimed by Kawasaki to be stiffer than last year’s extruded-aluminum frame, and uses swingarm-pivot and steering-head castings said to be stronger than those of the C-type. Brakes have been upgraded to include 12.6-inch front rotors in place of the C’s 12.2inch units. A reshaped fairing offers improved weather protection, and incorporates a redesigned dash that includes a fuel gauge in place of the C-type’s infuriating bright-red fuel-warning lights.

This redesigned fairing also incorporates what may be the most significant of the D-type’s changes: twin nostrils at the fairing’s high-pressure leading edge, immediately under the headlight, that serve as ram-air ducts for the bike’s airbox, which is 20 percent larger than last year’s. This intake system works with four 40mm Keihin carbs and enlarged exhaust canisters to extract a whopping 132 rear-wheel horsepower from the D-type’s engine-essentially the same six-speed, liquid-cooled, 16-valve, dohc unit used in the Ctype. That means it’s plenty quick, booting the ZX-1 ID through the quarter-mile in 10.56 seconds, making it the only sub-11-second bike here. Surprisingly, the big ZX did not live up to its early press releases and bust through the 180-mph barrier, posting “only” 176 mph, the same speed logged by last year’s model. Fear not; it’s still the fastest thing with two wheels and turnsignals, and has more than 20 mph in hand on the next fastest bike in this comparison test.

The Katana 1100 counters Kawasaki’s interest in change with its own interest in the status-quo. It hit the streets in

1988 carrying the engine of the GSX-R1 100 sportbike, with tuning altered just a bit to firm up the big Kat’s midrange punch. It was given improved spring and shock rates for the

1989 model year, and connecting rods with slightly larger, heavier big ends to help quell at least part of the vibration endemic to air-and-oil-cooled Suzuki 1100s. Since then, it has been left alone, except for color-scheme revisions. It still carries the 16-inch wheels it was bom with, it still uses two twin-piston calipers to grip 10.8-inch rotors up front and it still hauls around an electrically operated adjustableheight windscreen. Street racers love the Katana 1100 for several reasons. First, its engine is a powerhouse, a durable air-and-oil-cooled, dohc, 16-valve beast that drives through a five-speed transmission to blast the bike, with its 545pound dry weight, through the quarter-mile in 11.22 seconds. It also stirs up a top speed of 153 mph. Street racers also love the Katana because its 60.4-inch wheelbase makes it much easier to launch than the short-coupled GSX-R1100.

That leaves Honda’s CBR1000F, which is evolved from 1987’s 1000 Hurricane, and which was introduced in second-generation, CBR form to Europe in 1989. Cycle World went there, rode it in the rain in England, and proclaimed, “America, you need this bike.” Honda heard that proclamation and brought the bike here in 1990, where it ran headon into the newly introduced ZX-11C, against which it came in second in most straight performance contests. It was held out of the U.S. market in ’92, and now it’s back, almost as thoroughly revised as the new ZX-11 is, but in different ways, with different goals in mind. Where Kawasaki’s revision eyeballed performance, Honda’s keyed into mixing performance with sophistication, comfort and an interesting new braking system called LBS, for Linked Brake System (see accompanying story, page 38).

Changes to the CBR’s 16-valve, dohc, liquid-cooled, counterbalanced, 998cc engine concern only use of new, more wear-resistant materials for its valve seats and camchain sprockets. Additionally, the engine now inhales through vacuum-type semi-flat-slide Keihin carbs, a halfmillimeter smaller than those previously used for this bike. The engine may be the smallest of this bunch, but it still rockets the 572-pound machine through its sixspeed trans to tum 11.19 seconds at the dragstrip, and to crank off a top speed of 154 mph.

The Honda’s suspension-a single shock that is preload and rebounddamping adjustable at the rear, and a nonadjustable fork-remains unchanged except for slightly altered fork damping to accommodate the new front/rear-linked brakes. The bike’s 59.1-inch wheelbase also is unchanged, and so is its frame, an unlovely looking affair that is commendably rigid, but which places last in the body-off beauty pageant.

The CBR’s most obvious changes-if not the most significant ones—are reserved for the bike’s fairing. The hard-plastic tip-over bumpers are still there at the crankshaft ends, but styling is generally tightened and made more compact, with

the radiator exhaust ports enlarged and the fairing stays redesigned to reduce vibration. The headlight bucket is moved rearward about eight-tenths of an inch, and the front of the fairing is reshaped, Honda says, to focus the center of aerodynamic pressure more tightly on the area immediately in front of the steering head to make the bike seem more nimble at high speeds.

What confronts us, then, are four similar sportbikes, all with similar missions, all priced between $7000 and $9000, all well-finished, all capable of sport-riding, touring or commuting. But how similar are they, really? To find out, we went for an extended, multi-day sport-tour over some of our favorite backroads.

These are exactly the kind of roads the Katana 1100 seems meant for. And indeed, the Suzuki does well in such riding, at least until the pace gets wicked up past a sporting seven-tenths. The bike’s very strong engine and slick-shifting transmission work well enough, but it is let down by spring and damping rates that tend toward softness. This makes ground clearance a problem, with the footpeg feelers and the centerstand dragging in comers. Suzuki’s use of premium tires helps the Katana maintain a planted feel, and in general riding, the 1100 is very well behaved. It’s just that when a rider notches past sport-touring mode into an aggressive pace, the bike’s soft suspension allows it to move around slightly.

Also weighing against the Suzuki is its riding position, an odd mix of an upright, almost-touring stance for the upper body, with a seat-to-peg relationship that calls for acute bends of the knees, especially for taller riders. Its mirrors are so small and poorly placed that they’re almost useless, and its electric windscreen, in any of its positions, provides the least effective protection of any of the bikes in this group. For these reasons, the Katana, good as it is, finished fourth out of four in this comparison.

FJ 1200s are famed for their smooth, wide powerbands, and our testbike was no exception, but the FJ also rides on suspension that is soft and somewhat underdamped, and unlike the Suzuki, does not come with premium tires. So while it is a joy at seven-tenths riding, it, too, is a handful when the pace picks up and hard parts begin dragging.

But the FJ is the most comfortable bike of this group, with the best riding position and with better mirrors than the Suzuki. It also offers the best weather protection, and its engine ties with the Honda’s for being smoothest. That’s why we rank it third, a bit ahead of the Katana 1100.

Any Open-class motorcycle speaks loud-and-clear to the 16-year-old that lives inside each of us (don’t deny it, we know he’s in there). And the ZX-1 1, built with heavy emphasis on straight-line haul-ass, speaks to him the most loudly. Cranking this beast’s throttle WFO is a bit like being on the receiving end of Howitzer recoil. Kawasaki obviously has spent lots of time and resources on finding quantities of power; unfortunately, the bike’s quality of power doesn’t match its quantity. Throttle response isn’t particularly crisp, and small changes in throttle setting-the sort a rider makes during mid-comer throttle modulations-are rewarded with gross changes in power delivery, making it very difficult to be smooth on this bike. Lots of driveline lash, especially in lower gears, makes being smooth even more difficult.

The ZX’s suspension also challenges rider smoothness because compression damping is so firm that the ride is very choppy, and big bumps transfer heavy impacts to the rider through the bike’s well-shaped but very firm seat. The Kawasaki is at its best on smooth pavement, but unfortunately, the world is not a snooker table; on rough roads, the bike hunts and moves around as its tires deflect over bumps the suspension can’t react to. And when the ZX-l l is pushed hard in a bumpy comer, its front tire will chatter and skitter in protest. Additionally, while the ZX’s upgraded brakes are very powerful, they are not especially progressive. And because of relatively soft fork springs, jumping on the brakes causes the bike to dive heavily. All of which means managing the ZX at high speeds over bumpy pavement requires all the rider’s attention.

The Kawasaki’s riding position accommodates speed more than it accommodates comfort, with a long reach to lowish bars over a tall, humped tank. In a concession to rider comfort, the footpegs are low enough so that they can be touched down during hard cornering, a good trade-off. Its fairing works well, though it doesn’t offer the completeness of coverage the Yamaha’s does, and the shape of its windscreen allows a smooth, free flow of air over it and the rider.

And that brings us to the CBR1000F, picked by all four test riders as winner of this comparison. No, the Honda is nowhere near as fast as the Kawasaki-not in the quartermile, not in top speed. That’s because the Honda’s engine is a fairly subtle bmte. As its performance numbers indicate, it makes lots of horsepower. But its power doesn’t hit with a jolt, and thanks to its gear-driven counterbalancer, it is smooth enough to deceive. The deception lasts until you look down at the speedo and surprise yourself with the number the needle is pointing towards.

What isn’t deceptive is that the CBR’s steering is slow and heavy, and that the bike requires considerable muscle to flick from side-to-side. In spite of that, the CBR can be ridden more quickly in real-world conditions, more easily and more comfortably, than the Kawasaki can. In slow comers, it feels a bit top-heavy, but when speeds are increased, it is very composed and fluid, its suspension doing a fine job of damping out the jolts and bumps delivered by everyday rough pavement. The bike feels especially secure and planted in fast sweepers.

And then there’s that Linked Braking System. In most situations, the rider won’t be aware of the system at work-he’ll just use the brakes as he always does, with the expected result. But under very heavy braking, he’ll sense the LBS because when the brakes are nailed, the bike just hunkers down and stops with an absence of drama-check the CBR’s 60-to-zero distance-though the smoothest, shortest stops still require effective frontbrake/rear-brake management. It is possible to lock up the brakes, but only if the rider is really trying to do so.

Smoothness is the word that best sums up this bike. Engine, suspension, brakes, controls-all bear evidence of attention to detail that results in equipment that satisfies. On top of that, it’s the second least expensive bike here, $1300 less than the ZX, $1500 less than the ABS-equipped FJ1200.

So the CBR and the ZX finish a close 1-2, and your preference of one over the other will call for you to determine the following: Do you value the balanced approach to motorcycle performance, and the astounding attention to

detail that complete evolution brings? Or do you value the production of throwback, volcano-force horsepower? If the 16-year-old in you rears up and yells, ‘Horsepower, Dude,” and if you’re willing to trade off some comfort and refinement for a huge grin factor, the ZX-11 is your bike. But if you’re looking for a refined motorcycle that gives away a few percentage points of ultimate performance to gain attention to detail, composure and all-around ridability, the CBR1000F is the one for you. It certainly is the one for us.

It probably would be for Darwin, too.

HONDA CBR1000F

$7499

HORSEPOWER/ TORQUE

KAWASAKI ZX-11

$8799

SUZUKI KATANA 1100

$7299

YAMAHA FJ1200

$8999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart