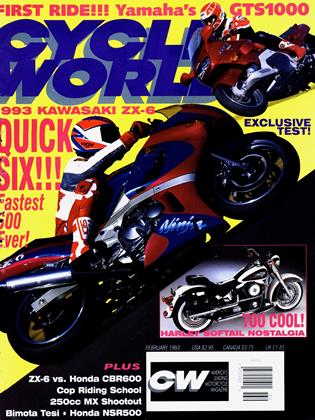

COP SCHOOL

RIDING ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE BADGE

JON F.THOMPSON

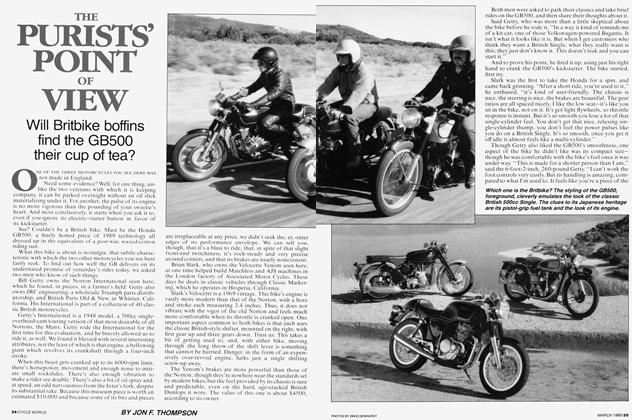

I AWAKEN TO FIND MYSELF IN A HOTEL ROOM IN MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN, where motorcycles are Harley-Davidsons and it's always 1950. My tele phone is shrieking its wakeup call; I've got just 30 minutes to get ready.

I'm here for Cop School-more properly known as Police Motorcycle Train ing, a week-long course designed and offered by Northwestern University. Its aim is to teach police officers to ride motorcycles in the line of duty. The course is tough, I'm told in preliminary telephone conversations. I might not pass. But I'll get the full curriculum, and will be treated not as some lightweight scribe, but as a student. Translation: I'll get the full ration of abuse. Hey, no problem.

My fellow-students all are policemen, nine of them, with a variety of street and patrol-riding experience, from a variety of large and small police depart ments. Our instructors are former motor cop Gary Cravillion, of Northwestern University's Traffic Institute, and Sgt. Nick Pierce, a motor officer with the Wisconsin State Police. Motor officers, by the way, are what these guys are, because the machines are "motors," never "motorcycles" or "bikes." It's an anachronistic term that reflects policedom's traditional values.

Pierce and Cravillion, it turns out, are sort of super-instructors here to oversee the progress of four student-instructors who will do most of the actual work.

"Pursuits are ¡ust races. I've never had anyone get away from me."

That work starts with an introductory classroom session in which we’re handed a course outline, part of which says, “At the end of this course, the student will demonstrate that he understands the basic techniques and possesses the skill and confidence to perform the problems and exercises presented in the prescribed manner.”

No worries. I know how to ride.

Wrong.

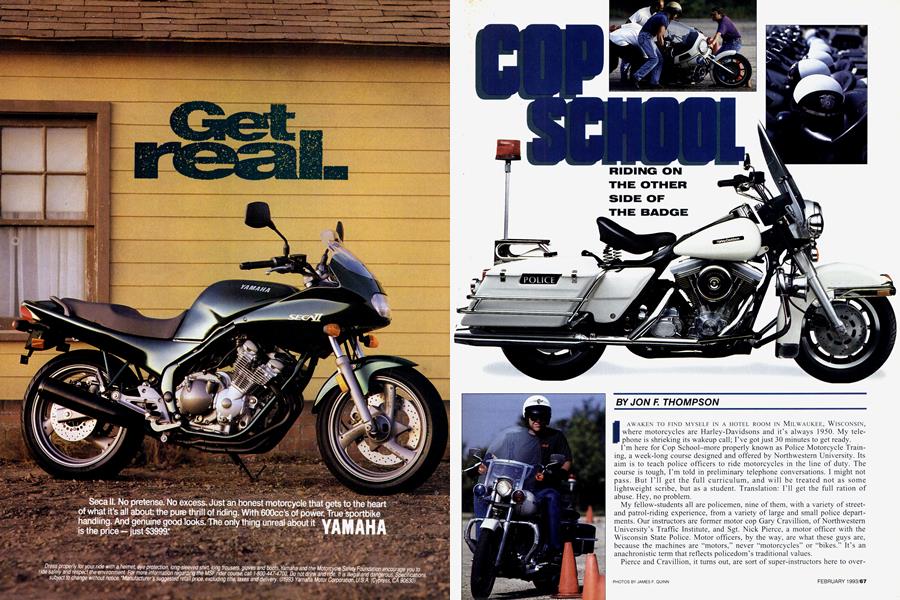

I don’t know anything about riding, a fact demonstrated soon after we’re assigned our school bikes from a fleet of FLHTP Electra Glides and FXRP Pursuit Glides. My motor is one of the latter, and is equipped with big, red lights-andsiren switches. Heh, heh, heh. Armed and dangerous.

The first lesson: How to mount and dismount the motor. I do it just like Eve always done it. Wrong! Students will mount and dismount their motors from the right-not from the left. This seems pretty dumb, until an instructor points out that when parking on a roadside during a traffic stop, a left-hand dismount puts the officer very close to the traffic lane, where he’s in fine position to be flattened. Right-hand dismounts it will be.

But getting on and off the bike becomes the least of my worries as the exercises begin. We start out by following student-instructor Lamar Ewell, of the Salt Lake City PD, in a single-file, ducks-in-a-row line around the huge parking lot behind Harley-Davidson’s Capital Avenue engine plant, where the course’s instruction takes place. Easy stuff-starts, stops, figure-eights. Piece of cake. It is, at least, until Ewell begins slaloming through narrowly spaced sets of rubber traffic cones. The key to this slowspeed maneuver-and indeed, all the rest of the drills we’ll learn this week-is a five-point litany repeated endlessly by the instructors: Head, eyes, throttle, clutch, brake.

Head and eyes in this context means exactly what it means during race or sport riding. Look where you aim to go, not at where you are. Look at the ground, eyeball the cone you’re weaving around, and you go where you’re looking. Which is to say, down. I went down a lot. So did the others. I soon overhear one of my classmates mutter, “I’ve picked that Harley up so many times I feel like I could bench-press the sumbitch.”

In addition to head-and-eye placement, crucial to not having to bench-press a Harley cop motor during low-speed exercises are throttle, clutch and brake control. Revs at 1200 to 1500, lightly ride the rear brake, and slip the clutch.

“Find the clutch’s gray area and use it,” we’re told over and over. What this means is, find that friendly area in clutch-plate travel where there is neither too little nor too much slippage. Balance that slippage against rear brakepedal pressure. Keep the revs up just a little, govern your motor’s forward motion by balancing clutch against brake.

Betting this just right is nowhere near as easy as it sounds, but the class gets plenty of practice. We do the Slow Cones, a traditional low-speed slalom around cones placed in a straight line. We do the Uneven Cones, tight looping turns around cones placed both longitudinally and latitudinally. And we do the Intersection, which is just that. It’s made up of 18-foot-wide, two-way traffic lanes, each end of which is blocked off. We enter at one end, turn right, then U-turn left, turn right, U-turn left, turn right, U-turn left, turn right, and exit. Apple pie, right?

Wrong. A Harley Big Twin won’t do a U-turn in 18 feet unless the rider has a bit of wit and skill. Gonna fall over?

A bit less clutch for just a touch of forward drive. Need a bit of control? Feather the brake just a little. All you’ve got to do is ride slowly, at monster lean angles, applying throttle, with the fork at full-lock. Not easy.

The afternoon of Day Two sees some fun stuff-HighSpeed Stop drills. Instructor Scott Peck, of the Salt Lake City PD, rips me for keeping the front-brake lever covered with two fingers, something I always do when street riding. He wants me to keep my mitt on the twistgrip, then reach out, and using all four fingers, nail a handful of Harley front brake from scratch. Some truly interesting high-speed front-end skids ensue before I get this wired.

The Rear-Brake Slides are more fun and less harrowing. We’re told to ride a course roughly an acre square, accelerating on the straights and turning left at cones marking > each of the course’s corners. But we do the turns by brakesliding the bike around the cones. Whoopie!

"I've picked that Harley up so many times I feel like I could bench-press the sumbitch."

More a problem for some is what the instructors call a Breeze-Out. This is intended as a low-speed tension-relaxer, a quick ride around the Harley-plant environs. Some of it is over heavily wooded dirt trails, and raises tension, instead of lowering it. Cop bikes as enduro mounts.

Day Three, everything changes. In addition to being very hot, it’s also raining. Wet, the newly sealed parking lot is as slick as deer guts on a doorknob. Perfect. It’s time for the Keyhole, an 18-foot circle marked in cones. Its entry, located at about six o’clock in the circle, is 5 feet wide, and about 5 feet deep. If you’re going to do the Keyhole counterclockwise, you enter from the left of the box, flick the bike hard to the right, just brush the three o’clock cone with the motor’s front tire, flick it hard fulllock left, lean in, look over your shoulder at the exit, and gas it. I’m convinced this simply cannot be accomplished. My conviction is burned to the ground, however, when Ray Watts, chief of the Terre Haute, Indiana PD and not a long-time motorcyclist, aces it. Every time. He’s laughing, having a ball. I hear one of his patrolmen, accompanying him through this class, call him “Chiefie.” Morale must be high in his department.

By now, most of the class is looking good. Even the one cop who has never ridden before is making fine progress. Still, I worry about catching a decent day’s-end evaluation. I’m riding well enough, but my performance is graded, on a scale of 7, with one 3, a bunch of 4s, and a single 5. Gonna have to bear down if I expect to pass this mutha. Bearing down is no problem as long as I can maintain my concentration, which usually is as hard and impenetrable as crystal. But as the day grinds on and fatigue sets in,

that changes. My mind wanders to Laura, my wife, or Matt, my son, or to whatever craziness might be erupting back at the offlce-and instantly my concentration shatters like a goblet dropped on a flagstone floor. No wonder I’m crawling back into my hotel room every night, whipped like a no-account dog.

Thursday, Day Four, rain still falling. We do 140-Degree Pullouts-head the bike to the right, take off heading 140 degrees to the left, without hitting the painted-line “school bus” parked just 13 feet away from the curb that the motor’s back tire is parked against. Another one that can’t be done. But we learn to do it. Head and eyes, gas, brake and clutch.

For a change-of-pace, we ride to the Harley factory, where the two Salt Lake City cops grill Senior Police Engineer Dan Venne because, they say, their Harley cop motors are too slow. Venne doesn’t want to hear it. We have lunch, take a quick look at Harley-Davidson’s hidden room of treasures-this contains one of just about everything Harley-Davidson has ever built, including two of the Porsche-designed Nova V-Four Harley prototypes-and head back to the classroom for a lecture from Pierce on streetand pursuit-riding. Don’t do it, Pierce tells us, it’s too dangerous. Leave it to the patrol cars. The two speeddemon student-instructors from Salt Lake City look at each other knowingly. One of them tells me later, “Pursuits are just races. I’ve never had anybody get away from me.”

We leave the factory, and I’m thinking, “One more halfday, then home. How hard can half a Friday be?” As usual, I’m clueless.

Friday is awful. It’s still very hot, but it’s dry, at least, and it had better be. It’s the day of the riding proficiency test. We all know this is coming, but none of us has any idea it will be quite so grim. It’s grim because we don’t just have to do all the patterns individually, keeping at them until we get them right. We have to link them all together, racing between each one in a sort of motorcycling biathlon. Our times will be kept. Dab a foot down, have a second added to our overall scores. Knock over a cone, gain a second. I’m in a > heap o’trouble, boy.

"There's a look of horror on his face, because he thinks he's going to die, and because he knows he's blown my test time."

The course starts with the 140 Pullout, which so far this morning nobody has made. Waiting for my tum, I make a few practice passes, getting about half of them. Then, I’m up.

Timekeeper and student-instructor Tony Meziere, a patrolman with the Johnson County, Indiana Sheriffs Department, tells me, “Anytime you’re ready....” I gas it and go, nailing this first pattern.

I am tucked-in under the paint, hard on the gas and heading for the next exercise 150 yards away when one of my classmates walks out of adjacent bushes. He’s preoccupied with zipping his fly, and steps right into my path. I brake and zig, he zigs. I brake harder and zag, he zags, a look of horror on his face because a) he thinks he’s going to die, and b) he knows he’s blown my test time. Finally I’m past, and into the Slow Cones. Then it’s the Intersection, another 150-or-so yards away. Then, the Triple-Lane Change, a problem we haven’t seen before. Next it’s the Bump-and-Go, a quick-start-quick-stop exercise, then the Keyhole. I haven’t done this correctly yet today, and I don’t do it correctly this time. I dab a»foot, and then gas it away, the back of the bike slithering around on the fresh sealer. My time is 3:41 plus a dab, a net time of 3:42, fast time so far.

It doesn’t hold up. Smiling Chief Watts beats me bigtime, and Patrolman Tom Schwaderer, from Harrison City, Pennsylvania, nips me by a second. But, hey, I’ll take it.

The class splits up, the successful ones to tour the Harley engine plant, the unsuccessful-those who have dropped their motors or blown too many pattems-to try the course again. Me? I passed, and I’m outta there, heading for the airport and home.

On the way, I’m wondering what I’ve learned that’s of value to a street/sport/touring rider. Mostly, it’s this: No matter what kind of riding you do, concentration is everything. So is head and eye placement. So is caution, so is defensive riding. I’ve also learned that like everyone else, cop-types resist the stereotypes we’re tempted to apply to them. Take my classmates, for instance. They range from beady-eyed professional to loud-mouth redneck to laidback mediator. Some have senses of humor, some don’t. Some are as skilled as any rider I know, some never will ride well. It takes all kinds, it seems, to ride cop motors.

It just takes some special ones to ride them well. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOr Best Offer

February 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Ducks of Autumn

February 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCComputers Vs. Intuition

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars Continue

February 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupOxygenated Fuel And the Motorcyclist

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron