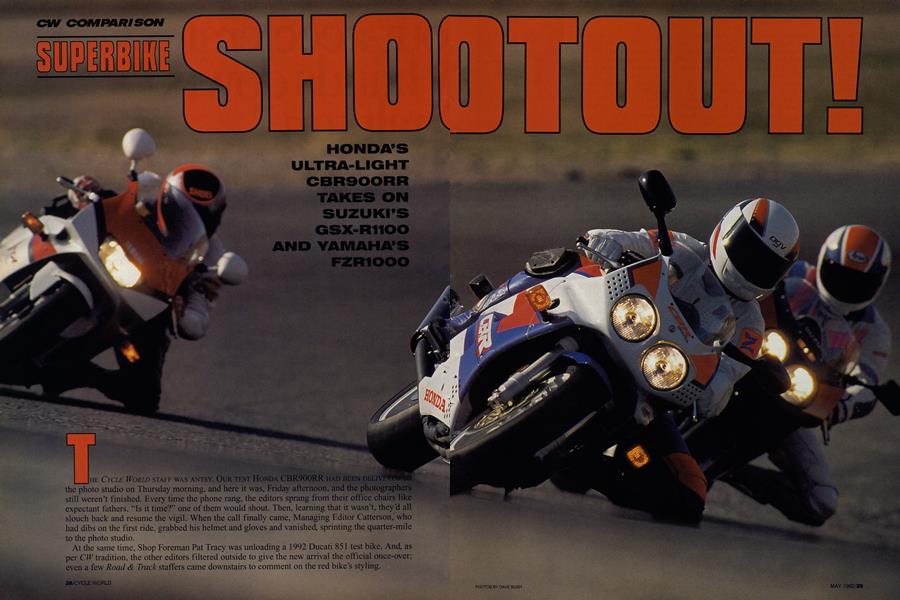

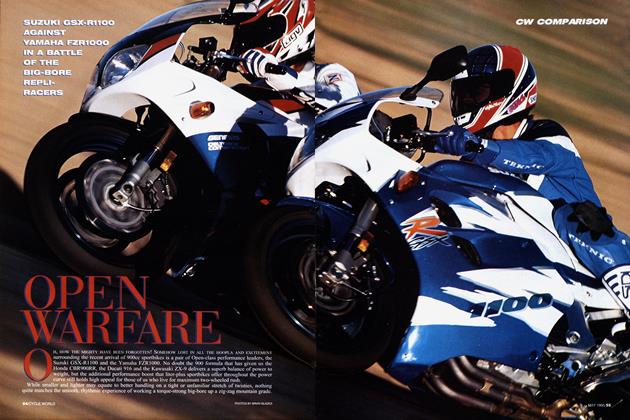

SUPERBIKE SHOOTOUT!

CW COMPARISON

HONDA'S ULTRA-LIGHT CBR900RR TAKES ON SUZUKI'S GSX-R1100 AND YAMAHA'S FZR1000

THE CYCLE WORLD STAFF WAS ANTSY. OUR TEST HONDA CBR900RR HAD BEEN DELIVERD TO the photo studio on Thursday morning, and here it was, Friday afternoon, and the photographers still weren’t finished. Every time the phone rang, the editors sprang from their office chairs like expectant fathers. “Is it time?” one of them would shout. Then, learning that it wasn’t, they’d all slouch back and resume the vigil. When the call finally came, Managing Editor Catterson, who

had dibs on the first ride, grabbed his helmet and gloves and vanished, sprinting the quarter-mile to the photo studio.

At the same time, Shop Foreman Pat Tracy was unloading a 1992 Ducati 851 test bike. And, as per CW tradition, the other editors filtered outside to give the new arrival the official once-over; even a few Road & Track staffers came downstairs to comment on the red bike’s styling.

The critique session soon came to a screaming halt, however, shattered by the sound of a rapidly approaching four-cylinder engine. Catterson wheelied the CBR900RR into the parking lot and skidded to a stop, an ear-to-ear grin visible when he popped off his helmet. “It’s true!” he exclaimed. “This thing is an 1100 in a 600 chassis.”

Suddenly, it was as though the Ducati didn’t even exist. The Honda looked bigger in the parking lot than it did in the preview photos, we decided, and was much wider through the midriff than we’d expected. Yet it was a loi smaller than the Suzuki GSX-R1100 and Yamaha FZR1000 parked a few feet away, the two bikes with which it would be compared over the course of the following week. Associate Editor Miles reckoned that the CBR looked like an FZR that had been squashed from either end, and the rest of us agreed.

A product of computeraided design, the CBR900RR is an extremely dense package, more so even than the CBR600F2, which it strongly resembles. The 900’s motor is hardly any larger than the 600’s. In fact, the entire motorcycle is hardly any bigger than its 600cc sibling.

Though none of the 900’s components are truly ground-

breaking, the bike still bristles with interesting pieces. Its fork, at first glance, looks to be upside-down, but in reality it is traditionally configured-albeit with massive, 45mm stanchion tubes and extruded aluminum sliders that are screwed and glued into huge castaluminum axle lugs, which also serve as mounting points for the pair of four-piston brake calipers. With its triangulated brace, the aluminum swingarm is somewhat reminiscent of those fitted to Yamaha’s monoshock roadracers 15 years ago. And although it is equipped with a shock very similar to that of the 600, the 900 employs a rising-rate linkage, whereas the smaller bike’s shock bolts directly to the swingarm.

There’s a hint of GP racebike in the 900’s appearance, too: in its tail-high attitude, in the holes drilled in its fairing nose and lowers, and in its racy paint job-be glad American Honda didn’t opt for the garish paint and graphics of the non-U.S. CBR900RR model, dubiously named the “Fire Blade.” On appearance alone, we concluded, the CBR was going to be a contender.

But enough about its looks. We’ve been looking at drawings and photos for months now. How does the CBR900RR work? And, perhaps most importantly, how does it compare to its competition? Though the 1992 FZR 1000 and GSXR1100 are mechanically unchanged for ’92, both received upside-down forks and other minor updates last year that made them better than ever. The FZR was especially impressive, and was voted Best Superbike in our annual Ten Best Bikes voting. The CBR would have to be pretty special to unseat its two established rivals.

We all took turns riding around the block, familiarizing ourselves with the new 900, and even in that brief period, the bike impressed us with its combination of lightweight handling and heavyweight performance. Just wait until we get it out on the backroads, we thought, and better yet, on the racetrack.

“Wait” was the operative word, because our comparison test occurred at the height of the worst rainstorms in recent Southern California history. Our first street ride, originally scheduled for Saturday, was washed away by torrents of curb-deep water. On Sunday, Associate Editor Canet took the CBR for a reconnaissance run up twisty Ortega Highway, but more rain and an endless parade of slow-moving motor homes made it a washout, too. The weather improved on Monday, but that day was reserved for cover photography, so there would be no real riding. Tuesday morning, Catterson took the long way to work on the CBR, heading up some local canyon passes, but the roads

were still a mess, and the three bikes had to go to the dyno that afternoon. More waiting.

At least the dyno results were enlightening. We’d expected the smaller-displacement CBR to produce less power than the FZR and GSX-R, but how much less? We’d heard claims of 120 horsepower for the CBR. Were they true?

Not quite. Hooked up to the dynamometer, the Honda produced 114 bhp at 10,500 rpm at the rear wheel, while the FZR made 123 bhp at 10,000 rpm and the GSX-R made 124 bhp at 9250 rpm. The CBR’s torque numbers were similarly low: 63.5 foot-pounds at 8250 rpm, compared to the FZR’s 71 at 8500 rpm and the GSX-R’s 76 at 7000 rpm. If the Honda was going to pull ahead of the Suzuki and Yamaha, it would not be on horsepower alone.

On Wednesday the weather cleared, and we finally got a chance to ride all three motorcycles back to back. And what better place to do so than Willow Springs International Raceway? In preparation for our racetrack testing, we spooned new rubber onto the FZR and GSX-R. The Honda comes stock with race-compound Bridgestone Battlaxs, and it wouldn’t be fair to compare it to the Suzuki and Yamaha, both of which wear street-compound Dunlops. We wanted to test motorcycles, not tires, so we fitted race-compound Battlaxs to the other two, as well.

Right out of the box, the CBR began to assert itself. After doing some morning photography, and with the tires still fresh, we put Canet on each of the bikes to see how quickly he could lap the 2.5-mile, nine-turn racetrack. The results were impressive: On the CBR, he turned a best lap of 1 minute, 31.9 seconds, more than a second quicker than he could manage on either of the other two bikes, and just a couple of seconds slower than his best-ever lap on a Formula USA GSX-R 1 100 racebike. On the stock GSX-R, Canet went 1:33.1. On the FZR, 1:33.5.

How could the Honda be that much quicker? Easy: It’s small and it’s light. On the CW scales, the CBR weighed 432 pounds dry-76 pounds less than the FZR and 94 pounds less than the GSX-R. What this means is that although the CBR makes less horsepower than its rivals, it has a superior power-to-weight ratio.

And that light weight-coupled with a short 55-inch wheelbase, a steep 24-degree rake and a mere 3.5 inches of trail-makes the CBR extremely easy to toss from side to side.

On the racetrack, the CBR flicks into corners with the nimbleness of a 250cc GP bike, with steering that remains neutral even while trail-braking. The bike sometimes feels busy, shaking its head slightly and wagging its tail, but never does it tankslap, weave or stray from its intended line. The 16-inch front wheel, fitted with a wide (130mm), relatively high (70-percent aspect ratio) radial tire, does not feel noticeably different than the 17-inchers of the other bikes; there’s little difference in rotational inertia, and no tendency to turn-in or understeer as the narrow, bias-ply 16-inchers fitted to early-’80s sportbikes sometimes did.

The CBR’s suspension is as close to streetbike perfection as anything we’ve sampled, plush yet taut, and with a range of adjustment to suit virtually any rider, regardless of weight or skill level. The CBR doesn’t have the seemingly limitless cornering clearance of, say, a Ducati 900SS, but only its footpegs and brake pedal touched down on the racetrack.

Though the CBR’s motor doesn’t feel as powerful as the others, it revs quickly and accelerates hard, endowing the bike with a propensity for wheelies. Running the 900 up through its extremely close-ratio six-speed gearbox is a joy-or at least it is once you’re past the tranny’s brief breakin period, during which the lever throw sometimes feels notchy. Braking is similarly enjoyable, though, with its powerful binders and short wheelbase, few bikes this side of a GP grid loft the rear wheel as easily as the CBR.

Compared to the nimble CBR, the FZR and GSX-R both feel big and heavy. The FZR is the most composed bike on the racetrack, though, feeling as if it’s on rails in high-speed turns, thanks to its rangy, 58.1-inch wheelbase. The FZR also has the best feeling front brakes; the CBR’s require a stronger pull on the lever, and the GSX-R’s feel mushy. But for racetrack use, the Yamaha’s suspension sacks too much, its wheelbase is too long and it has the least cornering clearance of the bunch-its footpegs and large exhaust canister touched down easily. Raising the rear of the bike would likely improve matters on the racetrack, but since there’s no provision for ride-height adjustment (on the FZR or the other two bikes), you’d have to fit a longer aftermarket shock.

The Yamaha’s motor, with its EXUP electronically controlled exhaust powervalve, feels the strongest on top, and like the Honda, it prefers to be kept spinning-though both bikes pull well enough off the bottom. The FZR is the smoothest running and slickest shifting, and it also has the most flywheel effect.

Despite being the heaviest bike here, and, with a 57.7-inch wheelbase, the second longest, the GSX-R has the most ground clearance, dragging only the pegs and the fairing lowers slightly. The GSX-R’s suspension lets the bike float more than the others, and as with last year’s model, it needs a heavier-rate shock spring. Even on its maximum springpreload setting, the rear suspension sacked too much. Still, it was the bike on which the majority of our testers felt most confident hanging the back end out; it slides more predictably than the FZR or CBR.

The GSX-R is King of Torque, and has the widest powerband of these three. Thus, it makes do with a five-speed transmission, and cares less which gear it is in than does the CBR or the FZR.

The Suzuki’s air-and-oil-cooled motor buzzes the most, though, especially under trailing throttle.

Some vibration seeps through the rubber-mounted handlebars and rubber-covered footpegs to the rider.

We left Willow Springs with renewed respect for the Honda. Down on horsepower and torque, the CBR’s light weight and agile handling had put it ahead of the sport’s heaviest hitters. On Thursday, we’d see how the 900 fared at Carlsbad Raceway’s dragstrip.

There, the Honda again came out on top. On the wheelieprone CBR, Canet still managed to blitz the quarter-mile in 10.59 seconds at 132.74 mph. The FZR spun its tire too easily and turned 10.64/133.92, and the GSX-R could only manage a 10.90/130.81. The Yamaha was pretty close to the Honda, but there can only be one winner.

Top-gear roll-ons netted the same result: The Honda again won, besting the torque-monster GSX-R by four-tenths of a second from 40-60 mph, and by one-tenth from 60-80. The Yamaha was a couple tenths farther off the pace.

On Friday, we took the bikes to our desert testing facility to see just how fast they’d go. This time, the results were different. While the CBR and GSX-R both sped past our radar gun at 159 mph, the Yamaha ripped off a scorching 165-mph pass, making it the fastest FZR we’ve yet tested. Canet noted that while all three bikes were stable at top speed, the Honda felt the most nervous, again likely a function of its radical, racer-like chassis geometry.

Okay, so the Honda bested its rivals at the roadrace track, the dragstrip and the roll-on tests, and put in a respectable showing for the radar gun. But how does it do on the street? Same story. Everything that lets the CBR excel on the racetrack lets it excel on the street, too. If anything, it feels even faster on the street than it does on the racetrack, yet its quick handling and forgiving, sure-footed nature let even novices comfortably test their limits.

The CBR’s racer-like seating position is as radical as that of Honda’s RC30 endurance-race replica, yet with an extremely close seat-to-handlebar relationship, the 900 is the most comfortable bike here for average-sized riders.

Only the width of its fuel tank intrudes upon rider comfort. In contrast, the FZR’s handlebars require a bit of a reach and the GSX-R’s footpegs are too high. If you buy your clothes at the Big and Tall Man’s store, you might be more comfortable on the FZR, but we’d diet, tuck in, and put up with being a bit cramped on the CBR. The payback is worth it.

About the only thing we can criticize the Honda for is its meager passenger accommodations. If your Significant Other insists on tagging along, you might be better off on the FZR or GSX-R. But if toting a passenger is one of your purchase priorities, we’d strongly consider purchasing a less-racy sportbike, like a Kawasaki ZX-ll, which works exceptionally well with a passenger.

Also, if money is a concern, the GSX-R 1100 starts to look better. At $7499, it retails for $800 less than the CBR and FZR, both of which list for $8299. Is the new 900RR $800 better than the GSX-R? Tough call if your budget is tight, but we’d vote yes.

If you’re a Kawasaki, Suzuki or Yamaha fan, however, all is not lost. Although the Honda CBR900RR will be in dealerships by the time this issue hits the newsstands, it’s technically a 1993 model. So, in theory at least, the others have a year to catch up. Will 1993 bring a liquid-cooled GSXR1100? A 24-valve FZR1000RR? A ZX-11R or ZX-12? Time will tell.

But for the foreseeable future, at least, Honda has redefined motorcycle performance, using equal parts of force and finesse. No other bike in the past 20 years has generated as much hype and hoopla as this lightweight flyer, but the CBR900RR lives up to its advance billing. It really is that good. □

HONDA CBR900RR

$8299

SUZUKI GSX-R1100

$7499

YAMAHA FZR1000

$8299