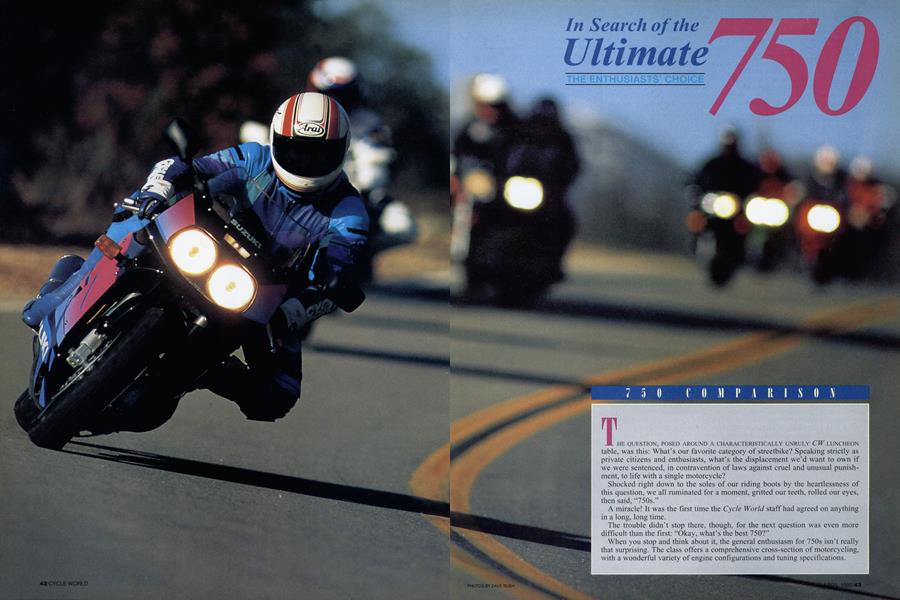

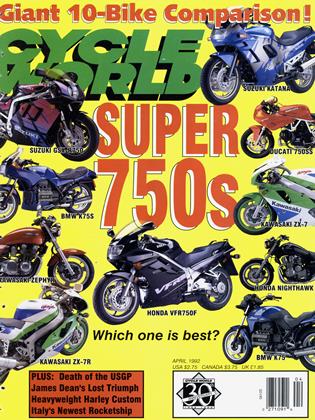

In Search of the Ultimate 750

THE ENTHUSIASTS' CHOICE

THE QUESTION, POSED AROUND A CHARACTERISTICALLY UNRULY CW LUNCHEON table, was this: What’s our favorite category of streetbike? Speaking strictly as private citizens and enthusiasts, what’s the displacement we’d want to own if we were sentenced, in contravention of laws against cruel and unusual punishment, to life with a single motorcycle?

Shocked right down to the soles of our riding boots by the heartlessness of this question, we all ruminated for a moment, gritted our teeth, rolled our eyes, then said, “750s.”

A miracle! It was the first time the Cycle World staff had agreed on anything in a long, long time.

The trouble didn’t stop there, though, for the next question was even more difficult than the first: “Okay, what’s the best 750?”

When you stop and think about it, the general enthusiasm for 750s isn’t really that surprising. The class offers a comprehensive cross-section of motorcycling, with a wonderful variety of engine configurations and tuning specifications.

A great many riders find 750s ideal because this engine size-three-quarters of a liter, 45 cubic inches-represents an ideal compromise between the intense, sporty lightness of the best 600s and the big-time, pavement-ripping energy delivered by the powerful but heavy and sometimes intimidating liter-class bikes.

A terrific compromise. And when someone then asks which is the best of the class, compromise again is the operable word. Picking the best overall 750 is a very different proposition from picking, say, the best 750 sportbike, or the best 750 standard.

We have selections for those classes and more, developed after an extended three-day trip on these bikes, with staffers Edwards, Thompson, Griewe, Canet and Miles, along with freelancer John Burns and roadracers Nigel Gale, Jason Pridmore and Danny Coe twisting throttles. But before we whip aside the Curtain of Secrecy to reveal the Enthusiasts’ Choice for Best 750cc Motorcycle in the Universe, allow us to introduce you to the 10 contenders, arranged in alphabetical order.

BMW K75

A rolling is. The anomaly, K75 is the that’s low-end what this of BMW’s high-tech K-series bikes. But it is powered by the smoothest engine in the BMW line, basically the lay-down, liquid-cöoled K100 Four with one cylinder lopped off. Its crank throws are timed to operate just three pistons, and it is equipped with a counterbalancer that tames the vibrations typically generated by engines with odd numbers of cylinders.

When computer nerds are confronted with equipment or softwear so well designed and developed that ordinary people can immediately use it, they label it “user-friendly.” That appellation is perfectly appropriate to the K75, a bike that we’d classify as a 750 standard. With its wide handlebar dictating an upright seating position and its fuel-injected engine delivering just moderate amounts of power, but with phenomenally smooth throttle response, this is an easy bike to get comfortable upon. What does take a bit of getting used to is the oddball jacking effect delivered through the single-sided swingarm by the bike’s shaft drive. Ridden with an unsmooth throttle hand, this causes the bike’s rear to hike up when power is applied, and sag when the throttle is chopped.

Like most of the rest of the bikes in this group, the K75 rolls on premiumgrade rubber-in this case from Metzeler, a Laser front and Metronic rear. And this combination, working with BMW-spec Showa suspension, delivers a secure feel and a good ride over all kinds of road surfaces.

The K75 is happiest when velocities are kept to moderate levels and riding style is fluid. Try to go really quickly, throw it into corners, nail the brakes, crank the power on hard, and this bike reminds you that it is softly sprung, tuned for midrange power, and heavy. Treat it as gently as you’d treat a lover, however, and it’ll reward you with a pleasant, though definitely not stirring, ride.

BMW K75S

Take add what anti-lock we’ve brakes just and been what saying, the Germans apparently think is a sporty fairing, and you’ve got the K75S. This uses the same running gear as the K75-same frame, same shock and made-for-BMW Showa fork, same engine, transmission and tires-but with low, narrow bars and fairing to give it a sport-touring flair.

The K75S works well enough, and feels as solid as a Bavarian boulder, but is let down by a soft engine and by paint which for this price (nearly $9000) should be as smooth as Alpine ice, but instead has a surface more like the skin of a

Portuguese orange. What it does have, though, is a seat by Corbin, handlebar switchgear that is quite unlike anybody else’s and which works very well indeed, excellent brake feel and the ability to haul you and a passenger comfortably and securely for long distances, at a moderate-to-quick sport-touring pace, without half trying.

The three-cylinder motor is tuned for smoothness and midrange oomph, and while it isn’t exactly, well, slow, hard-core performance-types probably won’t be satisfied with it, though its fuel injection system gives it very good throttle response. On curvy roads, it just doesn’t make enough power to keep up with most of the rest of this gang. That’s as well, probably, because the bike’s rear shock isn’t up to fast paces, especially over bumpy roads. Work it hard over such surfaces and it’ll soon wilt, letting the bike wallow.

Do we hear you muttering, “But this isn't a sportbike?” You’re right. It’s a civilized, low-pressure sporttourer, and as such, gives a good account of itself.

DUCATI 750SS

4 4ï|est bike to have in your garage 11 during a long winter, to burJLPnish and stare at, waiting for spring,” read the notes of one of our test riders.

Right, it’s a Ducati, with all the style, character and red paint we’ve come to expect from the Italians.

At 388 pounds, this bike is light for a 750. That’s good, because with its two-valve, air-cooled V-Twin, it’s also at the low end of the horsepower totem pole. That isn’t as much a negative as it may seem, however, because this little Duck makes its horsepower instantly, from 3000 rpm on up to about 8500, where its power starts to taper off, 500 revs short of redline. This, coupled with its nimbleness, stiff fork and crisply steering Dunlop radiais, allows the 750SS to keep pace with faster mounts. On this bike, you just think about changing directions, and you find you already have. Roll on the throttle, in any gear, and the thing blasts forwardmaybe not with the high-rpm intensity of the Japanese bikes, but with a solid feel that helps you understand the V-Twin aura.

Not quite as sporting in intent as the racetrack-oriented GSX-R and the two ZXs, this bike is much more comfortable to ride, thanks to its rational seating position and adjustable handlebar height.

Less rational, however, is Cagiva’s decision to market this bike, the price leader in its line, with just one disc brake up front. Only the smallest, lightest riders in our test group approved of this. The rest of us all greatly desired the additional stopping power an additional disc and caliper would have provided.

The Duck’s suspension is straightforward, a non-adjustable Showa inverted fork up front and non-linkage single shock with adjustable spring preload, and compression and rebound damping at the rear. The rear worked fine, though our lightest riders wanted a softer spring. The fork, too, would benefit from less spring, and a bit more compression and rebound damping. There is, after all, a reason the better class of fork comes with damping adjustments.

HONDA NIGHTAWK

This have is been a machine calling for, many and people after a slow sales start, it has found an audience, something Kawasaki’s 750 Zephyr has yet to do. But for superenthusiasts, the Nighthawk, built to a sharp-penciled price, doesn’t cut the mustard.

“Best bike to blame when you get blown off the road by one of our hired-gun racers,” wrote one of our testers. “Looks cheap, is slow, needs more brakes. For $4200, I could find a lot of used machines that would run rings around this thing,” noted another. “Not special, does not shine in any way,” wrote a third.

Other than that, how did we like the Nighthawk? It’s really not a bad bike, as long as you recognize its limitations. The Nighthawk is aimed squarely at re-entry buyers, the ones who have bailed out of motorcycling, but who now are looking for new bikes just like their old bikes.

The Nighthawk does, in most ways, reflect the attention to detail Flonda has become justly famed for. Its general level of finish is of high quality, belying the bike’s no-frills nature, and its controls all operate as slickly as deer guts on a doorknob.

That isn’t enough to save the Nighthawk in the Best 750 competition, though. Yes, it is the least expensive bike in this comparison, but it just doesn’t possess enough of any of the things most of us buy motorcycles for; not enough motor, not enough brakes, not enough suspension, not enough ground clearance, and, perhaps most importantly, not enough character. It’s fun, up to a point, but enthusiastic riders will, we suspect, quickly outgrow it.

HONDA VFR750F

The “Take recipe one for RC30 this racebike, one might stir read, in the need to mass produce it, add a healthy dollop of real-world usability, measure in a pinch of Acura-like quality, then grill lightly.”

The VFR750F is now in its third year of production. In some ways, thanks to a few detail improvements, it is better than ever. In one way, it has taken a giant step backwards.

The improvements are tiny ones. They involve changes to the bike’s carburetors, intake ports and silencers that result in a small increase in horsepower. They also involve the additions of a preload-adjustable fork and a shock with rebound-damping adjustment for a better controlled ride. All that’s good, working to make a wonderful bike even better.

The step back involves Honda’s attempt to uglify this bike. For 1990 and 1991, it was red, and it was gorgeous, the sort of machine you’d rob your own house to buy. In black, with its J.C. Whitney autograph-model tape graphics, it’s just homely.

It still works like crazy, though, as any motorcycle that costs more than $7000 should. Need to keep up with better riders on faster bikes? This is a machine that simplifies that task. Its engine is a marvel, with pulling power that never is peaky, but which just grows and grows on the way to an 11,500-rpm rev limit, all the while singing the sort of raspy, snarly exhaust note that only comes from a four-cylinder V-motor.

But the VFR is more than motor. It exudes a quality of concept and design that just isn’t found anywhere else in motorcycling, much less anywhere else in the 750 category. Its controls feel as though all operate on tiny needle bearings, its suspension provides excellent feel and handling while delivering a wonderfully plush ride, and its fit and finish make the bike seem the product not of Honda, but of its upscale automotive division, Acura. One of our testers summed up this bike by musing, “Makes you wonder how anything this good could be mass-produced.”

KAWASAKI ZEPHYR

This part isn’t of a developing just a motorcycle, strategy that it’s has its roots in the Japanese popularity of retrobikes. The Zephyr series, starting with the 550cc version, has sold so well in Japan that Kawasaki executives began shipping the things here, where the 550 and this bike, the 750, have bombed.

Too bad. The 750, especially, is an extremely satisfying motorcycle. It’s a member of the same standard category as Honda’s Nighthawk, but it’s better in every way-better brakes, better suspension, better engine, better riding position, and, as a result, much more fun to ride.

The Zephyr is a standard, but it’s equipped with a Europeanstyle low handlebar, better rear suspension than that fitted to the Honda CB750 N ighthawk, and an rpmhappy engine that invites the rider to twist its tail. The result is a motorcycle that is an absolute blast on a tight, winding road.

No, it isn’t as fast as a pure sportbike when the curves get serious. And, yes, if you’ve become used to a rich diet of four-valve-per-cylinder power, the charm of this bike might escape you. Still, it is exceedingly sure-footed, its steering is precise, its brakes very powerful. Okay, that aircooled engine sometimes does feel a little rough-hewn, and the chassis does suffer from a lack of clearance during hard cornering.

Which is to say, the stable, no-surprises Zephyr works like a standard is supposed to. We can’t imagine why this bike isn’t selling.

KAWASAKI ZX-7

Specificity you don’t can believe be a terrible it, consider thing. the If Kawasaki ZX-7. It is one of three bikes in this group that is very sharply focused upon hard-core sport riding, aimed specifically at riders who don’t mind spending time in a full-race tuck, who relish the thought of being a part of this bike’s high-visibility race-replica profile. Unfortunately, when dialing up the ZX-7, Kawasaki punched numbers into its computers and got back some wrong answers. As a result, the bike is, at best, a qualified success.

What Kawasaki did right was make this bike available in its stunning green/blue/white race livery. What it has done wrong is calibrate the bike’s su

harshly for most street riders. Also, the reach to its very low, clip-on-type handlebars is so long, and the seating position so hard against the back of the fuel tank, that unless he wants to start singing soprano, the ZX-7 rider had better be wearing an athletic cup.

And worst of all, this bike’s state-of-the-art engine doesn’t deliver the hard-hitting horsepower rush a sportbike in this category ought to. The Kawasaki ZX-7 is just painful to ride, without the payoff that ought to be derived from zinging its tach needle up into the engine’s power zone.

Can at least some of these problems be solved? Suspension would be one place to start. The ZX would benefit from a fully adjustable aftermarket shock-the stocker doesn’t possess a

full range of adjustability. Up front, lighter fork oil might be a good place to begin the experiments. But really, folks, this is a premium piece, and a buyer shouldn’t have to mess with it to make it right. On our comparison ride, when it came time for a bike swap, nobody wanted this one. Does that tell you anything?

KAWASAKI ZX-7R

MTow, this is more like it. A couple ! mj of grand more expensive than its 11 less exotic brother, and much more difficult to cope with around town, the 7R is a pure-blooded racebike that is worth the hassle involved in riding it.

Hassle? You bet. For starters, its riding position is every bit as uncompromising as that of the plain ZX-7, and it has no passenger accommodation. Even worse, it is geared so high, and its low-rpm carburetion is so lean, that the only way to get it rolling is to rev it to about a million rpm and slip the clutch up to about 30 mph. But then shift into second, nail the throttle, hang on, and grin.

This thing has motor.

It’s also got suspension that is almost as harsh and uncompromising as that of the ZX-7, but which is fully adjustable-not that we ever got it just right. Ever try to come up with suspension settings for one bike that fit 10 different riders, all of different sizes, weights and riding styles, when you’re all trading bikes every hour or so? Can’t be done. But when you take the time to carefully tailor this bike to your own requirements, and when you spend the energy it takes to solve its low-rpm carburetion problems, you’ll pronounce the results worth the trouble. Set up as it was, because of a bit of initial suspension softness, the 7R wallowed a little when it was flicked into a corner, but once there, it felt perfectly planted.

And when the curves straighten out? “Runs like cheap pantyhose,” said one tester, “A hundred miles of freeway droning is worth one fast sweeper on the R. Screw practicality, a motorcycle is inherently not a rational purchase.” Words to ride by.

SUZUKI GSX-R750

If sign you’re that smart, works, when you you don't find mess a dewith it. You stay with it, developing it carefully, changing it only when you’ve found a truly better way. Proof-positive that this approach works? The Suzuki GSX-R750.

Yes, an all-new, liquid-cooled GSXR750 is on the way. But, trust us, that is absolutely no excuse for waiting, if you think this might be the right bike for you. The ’92 version is a stunner, with truckloads of horsepower, incredible brakes and a chassis that allows the bike to be flung around corners hard enough to make your ears ring.

For all of its considerable elegance, the GSX-R still has its problems, including rattles and vibrations from its

engine. Ah, but there are compensations. Its fully and easily adjustable suspension works very well, and Suzuki’s engineers got the base spring and shock rates just right. As a result, the bike does not jounce the fillings out of your molars. It is extremely agile, and it delivers just the sort of feedback that we all want, but rarely get. When you’re heeled over in a corner modulating the power, or you're braking hard, a millisecond away from flicking the thing in, you feel exactly what the front tire is doing. This, friends, is rolling joy.

That joy is heightened when you crank the GSX-R’s throttle open. Acceleration is soft until the tach needle gets to about 7000 rpm, where the engine comes alive. By 7500, it’s in the fat part of its power production, blasting the bike out of corners, rocketing it down straights the way a proper 750cc race replica ought to run.

Downside? It would have to be the bike’s very aggressive riding position and its oddball zig-zag graphics. Ugh! But, as Mom used to say, “She may not be pretty, but she’s got a wonderful personality.” Good old Mom, bless her heart, might have been talking about this bike.

SUZUKI KATANA 750

We you’ve all like got to horsepower, be pretty dedicatbut ed to put up with the chiropractic riding position demanded by a GSX-R750 or ZX-7R. If you lack such dedication, but still lust for speed, shake hands with the Katana. Yes, we know, the thing is lumpy and plain looking, and we also know that Suzuki’s attempts to camouflage the Kat’s weird styling haven’t worked very well. You lose sight of all that, though, when you ride this bike.

It is powered by a very close relative of the GSX-R’s engine. The differences between the two are in detail only, and are found in the bore/stroke ratios and in the mechanics of valve actuation. The Katana’s motor retains the GSX-R’s sometimes-buzzy feel, but it makes all the horsepower you expect it to.

BMW K75

$6390

BMW K75S

$8990

DUCATI 750SS

$7350

Honda Nighthawk

$4299

kawasaki Zephyr

$4799

It puts that power to the ground through a chassis that is short on adjustment, but which benefits from very clever and appropriate spring and shock rates, and from Suzuki’s decision to field this bike on Metzeler tires. The result is that the Katana is exceedingly easy to get comfortable upon, and extremely easy to ride quickly. Its steering is light, precise and neutral in feel, its brakes powerful, its six-speed transmission positive and light-shifting.

For all that, though, there’s something about the bike’s nature that most of our testers found off-putting. Could it be the bike’s cartoony look, or its oversanitized lack of character and personality? We don’t know. We do know, though, that the Katana is a competent bike and a good value, even if it lacks a certain élan.

CONCLUSION

So, clutched here we tightly are, long-green in our sweaty cash lunch-hooks, ready to go out, right now, today, and buy one of these 10 motorcycles.

Which one?

That’s easy. We’ll take the Honda VFR750, please, thank you very much.

In spite of the paint job we love to hate, and in spite of a too-high purchase price, the VFR’s design and execution are absolutely inspired. For all-round use, its motor is the best in the class, its chassis provides the best compromise between ride and handling, and it is, by a Milwaukee mile, the best finished of the bunch. It is sufficiently tractable for no-worries commuting, comfortable enough for high-mile rides, and sporty enough for adrenaline-producing Sundaymorning blasts. Plus, with its neat swingarm, its V-Four engine and its newly uprated suspension, it’s got all the high-tech parts we could want.

Just thinking about going for another ride on this bike makes us grin like a possum eating bumblebees. Yep, Honda’s VFR750 is the pick of the litter.

Honda VFR750F

$7299

Kawasaki ZX-7

$6999

Kawasaki ZX-7R

$9449

Suzuki GSX-R750

$6699

Suzuki Katana

$5799

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUncle George's Last Ride

April 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

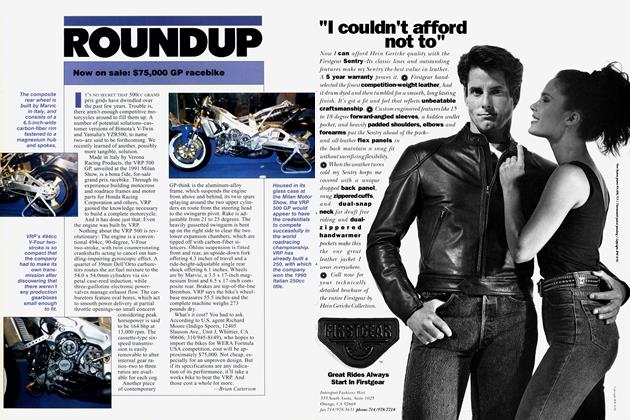

Roundup

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

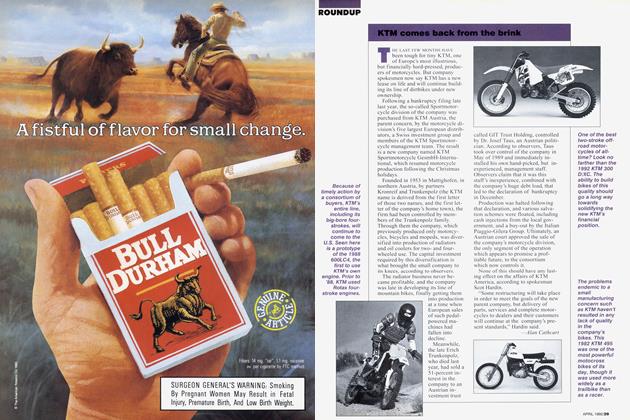

Roundup

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart