Uncle George’s last ride

UP FRONT

David Edwards

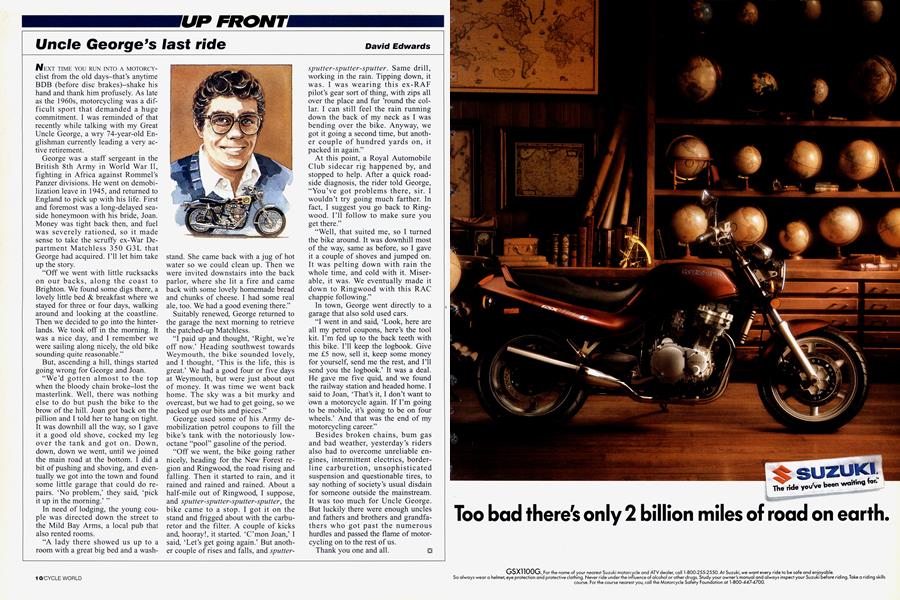

NEXT TIME YOU RUN INTO A MOTORCYclist from the old days-that’s anytime BDB (before disc brakes)-shake his hand and thank him profusely. As late as the 1960s, motorcycling was a difficult sport that demanded a huge commitment. I was reminded of that recently while talking with my Great Uncle George, a wry 74-year-old Englishman currently leading a very active retirement.

George was a staff sergeant in the British 8th Army in World War II, fighting in Africa against Rommel’s Panzer divisions. He went on demobilization leave in 1945, and returned to England to pick up with his life. First and foremost was a long-delayed seaside honeymoon with his bride, Joan. Money was tight back then, and fuel was severely rationed, so it made sense to take the scruffy ex-War Department Matchless 350 G3L that George had acquired. I’ll let him take up the story.

“Off we went with little rucksacks on our backs, along the coast to Brighton. We found some digs there, a lovely little bed & breakfast where we stayed for three or four days, walking around and looking at the coastline. Then we decided to go into the hinterlands. We took off in the morning. It was a nice day, and I remember we were sailing along nicely, the old bike sounding quite reasonable.”

But, ascending a hill, things started going wrong for George and Joan.

“We’d gotten almost to the top when the bloody chain broke-lost the masterlink. Well, there was nothing else to do but push the bike to the brow of the hill. Joan got back on the pillion and I told her to hang on tight. It was downhill all the way, so I gave it a good old shove, cocked my leg over the tank and got on. Down, down, down we went, until we joined the main road at the bottom. I did a bit of pushing and shoving, and eventually we got into the town and found some little garage that could do repairs. ‘No problem,’ they said, ‘pick it up in the morning.’ ”

In need of lodging, the young couple was directed down the street to the Mild Bay Arms, a local pub that also rented rooms.

“A lady there showed us up to a room with a great big bed and a washstand. She came back with a jug of hot water so we could clean up. Then we were invited downstairs into the back parlor, where she lit a fire and came back with some lovely homemade bread and chunks of cheese. I had some real ale, too. We had a good evening there.”

Suitably renewed, George returned to the garage the next morning to retrieve the patched-up Matchless.

“I paid up and thought, ‘Right, we’re off now.’ Heading southwest towards Weymouth, the bike sounded lovely, and I thought, ‘This is the life, this is great.’ We had a good four or five days at Weymouth, but were just about out of money. It was time we went back home. The sky was a bit murky and overcast, but we had to get going, so we packed up our bits and pieces.”

George used some of his Army demobilization petrol coupons to fill the bike’s tank with the notoriously lowoctane “pool” gasoline of the period.

“Off we went, the bike going rather nicely, heading for the New Forest region and Ringwood, the road rising and falling. Then it started to rain, and it rained and rained and rained. About a half-mile out of Ringwood, I suppose, and sputter-sputter-sputter-sputter, the bike came to a stop. I got it on the stand and frigged about with the carburetor and the filter. A couple of kicks and, hooray!, it started. ‘C’mon Joan,’ I said, ‘Let’s get going again.’ But another couple of rises and falls, and sputtersputter-sputter-sputter. Same drill, working in the rain. Tipping down, it was. I was wearing this ex-RAF pilot’s gear sort of thing, with zips all over the place and fur ’round the collar. I can still feel the rain running down the back of my neck as I was bending over the bike. Anyway, we got it going a second time, but another couple of hundred yards on, it packed in again.”

At this point, a Royal Automobile Club sidecar rig happened by, and stopped to help. After a quick roadside diagnosis, the rider told George, “You’ve got problems there, sir. I wouldn’t try going much farther. In fact, I suggest you go back to Ringwood. I’ll follow to make sure you get there.”

“Well, that suited me, so I turned the bike around. It was downhill most of the way, same as before, so I gave it a couple of shoves and jumped on. It was pelting down with rain the whole time, and cold with it. Miserable, it was. We eventually made it down to Ringwood with this RAC chappie following.”

In town, George went directly to a garage that also sold used cars.

“I went in and said, ‘Look, here are all my petrol coupons, here’s the tool kit. I’m fed up to the back teeth with this bike. I’ll keep the logbook. Give me £5 now, sell it, keep some money for yourself, send me the rest, and I’ll send you the logbook.’ It was a deal. He gave me five quid, and we found the railway station and headed home. I said to Joan, ‘That’s it, I don’t want to own a motorcycle again. If I’m going to be mobile, it’s going to be on four wheels.’ And that was the end of my motorcycling career.”

Besides broken chains, bum gas and bad weather, yesterday’s riders also had to overcome unreliable engines, intermittent electrics, borderline carburetion, unsophisticated suspension and questionable tires, to say nothing of society’s usual disdain for someone outside the mainstream. It was too much for Uncle George. But luckily there were enough uncles and fathers and brothers and grandfathers who got past the numerous hurdles and passed the flame of motorcycling on to the rest of us.

Thank you one and all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

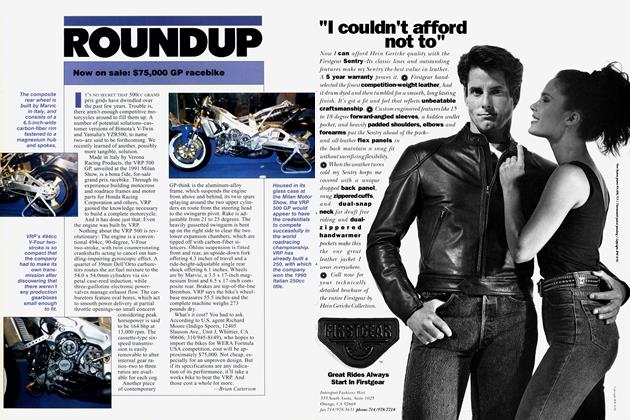

Roundup

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

April 1992 By Brian Catterson