STANDARD PROCEDURE

WHY THE MANUFACTURERS ARE LOOKING AHEAD BY LOOKING BACK

JONE THOMPSON

IF, AS THE TONGUE-IN-CHEEK SAYing goes, “on the eighth day, God created motorcycles,” without doubt the motorcycles He created were, in their form and in their function, standards.

Of course. Motorcycles of any type are capable of providing great joy, but standards are the most versatile, most useful of them all, capable of being whatever their riders want them to be.

So it is of special interest that after nearly a decade of ever-more-intense specialization, after a period during which the standard-style motorcycle became as nearly extinct as the bison once was, after the proliferation of specific-use-intensive types of motorcycles. once again the move, in at least part of the motorcycling world, is towards standards.

Does the term “standard motorcycle” need definition? Probably not. But just in case, here's one which will, because of its generality, do for a start: A standard is any motorcycle not intended, by virtue of styling or engineering, to till a narrow riding style or marketing niche.

Want to sharpen that focus a little? Well, standards usually—but not always—have tubular handlebars, flatfish, unstepped seats, upright, noncruiser riding positions and an openness of look made possible by the lack of factory-supplied fairings.

What complicates things is that each and every of the above specifics can be modified, as an owner wishes, and as he fits different bits and pieces to mold the bike so that it perfectly matches his tastes and riding style. And all of that makes it more difficult to exactly define the term “standard.”

That difficulty however, has not stopped the Big Four manufacturers. This year they’ve clutched the generalist concept to their corporate bosoms as tightly as they’ve adopted other more task-specific types of motorcycles, because continued flatness of new-motorcycle sales is holding their feet to the fires of commerce.

Thus Honda offers the Night hawk 750, Kawasaki the Zephyr 750 and 550, Suzuki the GSX1 10ÖG, VX800 and GS500. And let's not forget that America, Germany and Italy also offer standard-style bikes, such as the Harley Sportster and FXR series, the BMW' K75 and R 100, and the Moto Guzzi 1000S.

So, there’s something happening here, an apparent ground-swell of new interest in a segment the manufacturers know they must tap.

Much of that interest comes because survey numbers indicate that about 2 1 percent of all purchasers of new streetbikes—one in five, in other words—are what are called re-entry buyers. And in the words of John Porter, a corporate planner for Yamaha. “Every customer is important, and 20 percent of them is a sizable

and profitable business niche.”

What’s a re-entry buyer? Simply someone who used to ride, who stopped for a while, and who once again is prowling motorcycle showrooms, almost readv to buv. checking out what’s hot and what’s not. Some refinements on that theme might be that he’s a buyer who hasn’t owned a motorcycle for from as little as two years to as many as six years or more, or that he still owns a bike, but hasn’t ridden it for some time. How big is this potential buyer pool? According to Yamaha’s Porter, “For almost 25 percent of American men. motorcycling has been one of the past pleasures.”

That re-entry customer is. according to the best thinking and research of the manufacturers, in his 40s and towards the end of what’s called the “middle-marriage” phase of his life. He finds himself with some equity in his home, with payments that don’t seem as massive as they once may have. He’s got increased amounts of recreational time and, with the maturity of his children, increased amounts of disposable income. And he begins thinking, once again, of the things he did for fun before marriage, before children, before the hard, heavy hit of the first few vears of mortgage payments.

The standard motorcycle is an element in the Big Four’s competition for the hearts and minds of these buyers, explains Ray Blank, American Honda's assistant vice president of motorcycle operations, because, “When he left the motorcycle market. there wasn't todav’s degree of segmentation. When he comes into a dealership today, he sees special tools, special-purpose motorcycles. He doesn't see anything like the type of bike he saw when he left motorcycling. He's not ready to put himself into any specific niche. He likes performance. but he’s not ready to put himself into a sportbike crouch, and he's not ready for the expense of a turn-key tourer. So what does he look at?"

Each of the Big hour manufacturers has been struggling with that question, and to date, three of them have provided hard-metal answers, leaving only Yamaha without a purpose-built player in the Great Standard Sweepstakes, though insiders tell us one definitely is in the pipeline.

Perhaps the most highly touted of those standards, and certain!v the most heavily researched, is the Honda Nighthawk 750. everv feature and contour of which has been very careful ly and purposefully shaped, through use of surveys and focus groups, to appeal to a very specific someone looking for a general-use, ge n e ra î-i n terest moto rc v c 1 e.

According to Blank, the presence of a Nighthawk 750 in a Honda showroom means that when a former rider comes in for a look-see, “He gets to see a motorcycle updated from the time he left (the market), but at least of the same concept he saw back then. He’s comfortable with it because it’s an updated version of what he saw when he left motorcycling. Also, the pricing is legitimate. When the re-entry buyer left motorcycling, bikes were $2400, $2500. A Nighthawk is $3995, and he can rationalize that in his mind, where he might not want to spend $ 10,000plus for a luxury tourer, or $6000 to $7000 for a sportbike."

Just how successful is Honda’s investment in production of the Nighthawk 750. and its entry-level sibling, the Nighthawk 250. remains to be seen. Dealer reaction to the bikes, and especially to the four-cylinder, air-cooled 750, has been especially favorable. Blank said. But what of the buyers themselves, those for whom the bike was specifically designed?

“We can't sav yet. But for what it

delivers, its value is very easily perceived. So we expect it to be quite successful," says Blank.

One possible fly in the ointment of Honda’s research is the fact that reentry buyers seem to be buying lots of things other than standard-style bikes, including rational sportbikes such as Suzuki’s Katana 750. and also a steady trickle of dual-purpose bikes, especially those in the smallbore division, such as Suzuki's DR350S.

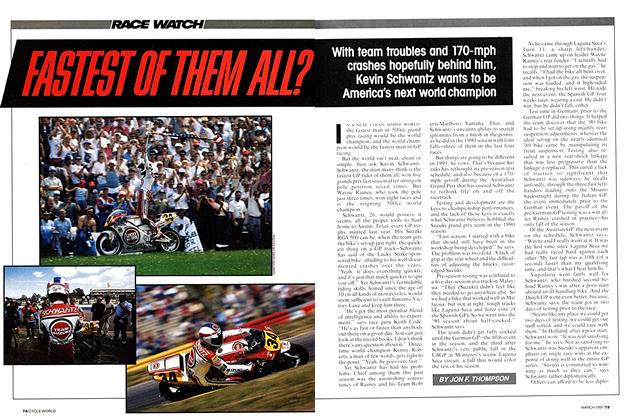

And that, of course, is music to the ears of Suzuki, which, just in case, has not one, but three standard-style bikes this year —the GS500, the VX800. and the new GSX 1 100G.

Mark Blackwell, marketing director of the company's motorcycle/marine division, points out that Suzuki is going after re-entry buyers in a three-tiered approach. For those shocked by contemporary sticker prices, it offers the $3149 GS500. But, says Blackwell, Suzuki's research also showed what he calls “tremendous untapped demand" for a true street-legal, dual-purpose motorcycle based on dirt technology, and he says that’s why the company developed its DR250S and DR350S bikes. Says Blackwell, “We see dualpurpose bikes as the next cool thing to have, kind of like driving a Jeep."

And Suzuki also places tremendous importance on the potential of the shaft-driven VX800 and GSX1100G, which are appealing, Blackwell says, because they're low in maintenance and offer comfortable riding positions.

“They're modern, but with classic styling cues," he says, “and. in the case of the VX800, you’re investing $4500, not $6000 or'S7000.”

Customer response to the V-Twin VX800, introduced in 1990, has so far been cool, but the GSX 1 I00G. Blackwell says, has been much more warmly received. He says. “At a recent show, we had a guy who rode 400 miles just to see the bike. It’s got four-cylinder performance and a comfortable riding position and versatility. Technology still drives the market, so the trick is to capture the imagination of the enthusiasts, and give them what they want."

Kawasaki’s interest in the future of the standard motorcycle is no less intense than that of the other manufacturers. but its stylists and engineers have put a slightly different spin on their version of the standard. The company’s stylists have made sure that the two Zephyrs, in 550cc and 750ec forms, both take their styling cues from the Kawasaki 900s, 1000s and 1 100s of the 1970s and early 1980s, as hot-rodded and streetraced e v e r y w h e re.

Says Bob Mollit. Kawasaki’s vicepresident of marketing, “You expect the customer to respond to a lower cost of ownership, but he’s also relating to an earlier dream, or experience; just like 1 may look back longingly at a BSA Lightning or a Triumph Bonneville, there’s some reason to believe that these (re-entry buyers) have a warm spot in their hearts for that hot-rod look, and this played a part in the styling of the Zephyr, which hearkens back to when this type of motorcycle was absolutely king of the hill."

Mollit says the company has particularly high hopes for the 75()cc version of the bike because, he believes. “That’s a seminal number; the perception is that if you're a serious rider, you need a 750."

But while Honda and Suzuki carefully planned all their entries, regardless of engine size. Kawasaki’s Zephyr, to hear Moffit tel! it, just happened.

“The Zephyr is not something we (the company’s American arm) planned. We just saw' it being overwhelmingly successful in Japan, where people were turning away from their sportbikes (in order to buy Zephyrs)."

And now that the Zephyr not only is available here in the U.S.. but is available in two sizes, he adds, “We’re counting on it to capture the interest of the re-entry buyer."

Whether it will, of course, remains to be seen. But the mere existence of bikes like the two Zephyrs, the two Nighthawks, and Suzuki’s two dualpurpose bikes and its three standards, seems* eloquent proof of the renewed enthusiasm and commitment with which the people who design, build and sell motorcycles are attempting to satisfy the needs of the people who ride and enjoy them. And that kind of enthusiasm and commitment can only work to the benefit everyone who delights in riding, no matter what sort of bike thev like to ride. Eä

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBusiness As Usual

April 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargePas-De-Deux On Pine Avenue

April 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsStaying Hungry

April 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Italian-Japanese-British-Swiss-Kiwi Connection

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Great Guzzi Buy-Out of 1991

April 1991 By Jon F. Thompson