KAWASAKI EX500 vs. SUZUKI GS500

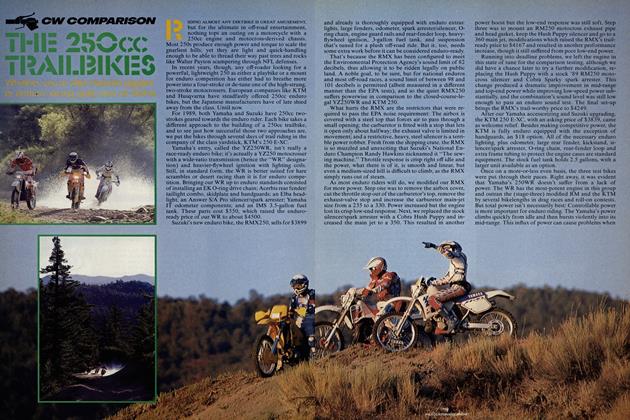

CW COMPARISON

Peas in a pod, or orange vs. tangerine?

IF THERE'S ANYTHING THE HEARTS and minds—and therefore the wallets—of most enthusiasts respond to, it’s technology.

But that response sometimes overlooks a number of interesting pieces that the latest in technology has marched right past, and the result is that some of those pieces verge on becoming two-wheeled wallflowers, in spite of their very reasonable performance and price tags.

"Two such bikes are the Kawasaki EX500 and the Suzuki GS500. In some important ways, this pair would seem to reflect some of the best of motorcycling's traditions, especially now, when would-be buyers seem to be calling for a return to the sort of basics represented by the standardstyle bike of a decade ago. It can be argued, in fact, that both of these bikes are standards—even with plastic bodywork attached—by virtue of their simplicity and their uncomplicated. comfortable riding positions. Indeed, it can further be argued that they're birds of a feather, two peas in a pod. twins of different parents.

The Kawasaki, which for four straight years has been named to Cycle Worlds Ten Best list, appeared in 1987 powered by an engine that was a few years old even then. Its motor came to it from the 454 LTD cruiser. And that engine was a development. in effect, of half a 1984 Ninja 900 engine. The bike, virtually unchanged except for color scheme since its introduction, originally appeared in a CW comparison which also included a Cagiva Alazzurra 650SS and a Moto Guzzi V65 Lario. It soundlv trounced both. It's done well on the showroom floor, too; last year, it was Kawasaki's sales leader by a wide margin.

The Suzuki first appeared in 1989—using a development of an engine that originally saw service in the undistinguished GS450E econobike of a decade ago—as Suzuki’s offering to those seeking an entry-level bike, a niche it fills quite nicely. Indeed, company officials are pleased with the GS500 sales, which have been helped by Suzuki’s innovative firsttime buyer’s program.

But while these two bikes may be competing for the same customer, they’re not as alike as they might seem. Similar, sure. But only as an orange is similar to a tangerine.

Yes, each uses a vextical-Twin, dohc engine and each uses a sixspeed transmission. Each uses a single front disc brake and a single-shock rear suspension. Each comes with suspension componentry that is without adjustment, except for rearspring preload. Each uses a modern, twin-spar frame, and each offers an upright, comfortable riding position. But hidden within these similarities are some significant differences.

The Suzuki’s engine is air-cooled, while the Kawasaki’s is liquidcooled. The Suzuki’s engine uses two valves per cylinder, the Kawasaki’s uses four. The Kawasaki uses individual cast handlebars while the Suzuki uses a single tubular handlebar. The Suzuki’s instruments are traditional in style and consist of a tach arid speedo plus the odd warning light while the Kawasaki’s, enclosed in an automotive-type pod, are more complete. And, visually, the most profound difference: The Suzuki comes standard, for its $3149 list price, bare and unclothed, while the $3529 Kawasaki comes with a nicely finished sport-style upper fairing that looks great and works pretty well in the bargain.

Kawasaki EX500

$3529

Kawasaki Motors Corp.

Suzuki GS500

$3149

American Suzuki Motor Corp.

Just to even things up a bit for the purposes of this comparison, we added Suzuki's optional quarter-fairing and engine cowling ($229.95 and $199.95, respectively). These pieces smarten the little Suzuki's look, and that quarter-fairing really does divert a bit of wind blast from the rider's torso once the bike gets up to speed. But, alas, those pieces cannot make the Suzuki the equal of the Kawasaki.

For two bikes so outwardly similar, the surprise is how different each feels from the other. These differences are felt from the first moments aboard each. The riding positions are comparable, with seat-comfort quotients and bar heights that are about the same, but the Kawasaki's bars are narrower than the Suzuki's, and therefore impart a sportier feel, even at a standstill.

The differences between the pair continue to show as the bikes pull away from a stop. The Kawasaki makes power right off idle, the Suzuki doesn’t. The Kawasaki's rider just drops the clutch and leaves, while the Suzuki pilot must bring the revs up and be careful not to bog the engine as he releases the clutch.

Once rolling aboard the Suzuki, not much happens until the tach needle gets to about 3000 rpm. with the engine not coming fully and completely awake until the needle swings around to the 8000-rpm mark. Once there, it makes modest amounts of power on up to 10,500 rpm, 500 rpm below its rev limit. Not much point in revving the bike all the way to 11,000. A shift at 10.5 drops the tach needle to 9000—smack in the middle of the bike’s most usable power range—and allows the rider to keep the little engine on the boil, an absolute requirement for any kind of brisk pace. None of this, mind you, is necessary for gentle cruises or one-up touring rides, but to extract max performance from the little GS, the rider has to use at least one gear lower than he’d usually expect to be in. Failure to do that allows the tach needle to fall below 8000, and when that happens, the pace of things slows right down, until the rider backshifts and gets the engine spinning again.

The Kawasaki also has a definite rpm range in which it makes its best power—it pulls well from 7000 rpm to about 10,300 rpm. As with the Suzuki, there’s little need to rev the engine beyond that point. But unlike the Suzuki, the rider doesn’t pay a penalty if he lets the revs fall precipitously. Yes, a downshift will help, but in most cases the Kawasaki’s engine has sufficient torque so that the revs will pick right up again with only a twist of the throttle.

Performance figures for the two bikes bear out their respective feels. The EX whipped through the quarter-mile in 12.64 seconds at almost 104 mph; the Suzuki turned 13.60 at 96 mph. Top-speed figures were 119 for the EX and 111 for the Suzuki. Top-gear roll-ons were also in favor of the EX. But speed is relative. As willing partners in crime, both of these bikes are great fun to slap-shift through the gearbox, and are plenty quick enough to buy you all the trouble with local traffic cops you’re ever likely to require, so a bit of caution would not be misplaced.

Neither bike exhibited flat spots in throttle response. The only evident glitch involved the Suzuki, which was cold-blooded enough to require some choke for the first few miles after a cold-start, a condition exacerbated by the engine’s softness at low rpm. So, releasing the clutch with too few revs and too little choke instantly will kill the engine. The Kawasaki also required a bit of choke on cold-starts, but the bike could be ridden away immediately, and the choke could be opened almost at once.

As it turns out, the Suzuki's chassis exhibits just about the same amount of performance potential as its engine. Which is to say, it's no slouch, but it clearly wasn't designed as a performance missile, either.

One noticeable difference between it and the Kawasaki is that turning the GS requires a relatively heavy push on the handlebar to initiate countersteer to make the bike peel into a corner. By comparison, the EX’s steering is so light the rider can almost steer it by putting knee pressure into the bike's fuel tank. In spite of the fact that the GS’s steering geometry is two degrees steeper than the EX’s, the Suzuki’s steering feels much slower and heavier than the Kawasaki’s, which not only is lightning quick in direction changes, but which is also very quick in sideto-side transitions, this latter being one of the benefits of the EX’s 16inch wheels. For beginning riders, though, the GS might be the better, more reassuring choice, courtesy of that deliberate steering.

If the Kawasaki is the bike for corners, and it is, it's also the bike for bumps. It’s suspension is a little harsh over the biggest jolts, but it remains far less upset by mid-corner rough spots than the Suzuki, which suffers from insufficient damping, especially at the rear, in both directions, and this lets sudden impacts upset it. This also allows the bike to pogo on its rear suspension when it’s leaned over in hard cornering. And in really quick going, when heavy suspension loads are being fed into the bike’s chassis, this can combine with just enough head shake to let the rider know his mount isn’t terribly comfortable with such use. Additionally, the GS’s fork is slightly underdamped and gets a bit choppy under hard braking, with too little damping to keep it from a high-frequency pogo as the fork's springs are first compressed on braking and then react too quickly to that compression.

The Kawasaki, meanwhile, exhibits no such untoward behavior, and this is one of the reasons it makes such a terrific small-bore racebike (see “Weekend Racer,” page 64).

But an important area where the GS excels the EX is in brake feel. The Suzuki’s front lever feels firm and lets the rider know just what the front tire is doing. The Kawasaki's front brake lever just feels mushy.

In all other performance areas, however, the Suzuki, while a perfectly fine machine, just isn’t competitive with the Kawasaki, and it doesn't matter that what we're talking about are the differences between oranges and tangerines. The Suzuki isn't equipped as completely, it's slower and its chassis doesn't work as well. Itjust isn'tas satisfyinga motorcycle as is the EX500.

The 500 to buy? The Kawasaki, no question. It's $380 more expensive than the bare GS500, but—trust us on this one—it works well enough to be worth the difference.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBusiness As Usual

April 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargePas-De-Deux On Pine Avenue

April 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsStaying Hungry

April 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Italian-Japanese-British-Swiss-Kiwi Connection

April 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Great Guzzi Buy-Out of 1991

April 1991 By Jon F. Thompson