STEALTH CYCLES

"I'S NOT JUST A JOB. IT'S AN ADVENTURE." AND YOU might figure. "Well, hell, if it involves getting paid to roost around on motorcycles, maybe I oughta join up."

Oh yes, the U.S. Army does employ motorcycles. Or at least, says it plans to.

And not for any E1 Wimpo job like hauling orders and scouting reports from Post A to Post B, either, which is the way motorcycles mostly were used in World Wars I and II, a.k.a. The War To End All Wars and The Big One.

No way. What Today’s Army has in mind is putting sneaky, camo-faced Special Operations troops-we wouldn’t call them commandos, though you might-on motorcycles so they can prowl around behind enemy lines, toting miniature radios and tricky weapons, wasting bad guys and generally wreaking havoc upon the Forces of Darkness.

In fact, the Recent Unpleasantness In The Gulf would have been a terrific place to start this not-quite-clandestine adventure in motorcycling.

Just one trouble: The Army was late. It wasn t, in fact, anywhere near having its act sufficiently together to deploy the unit of motorcycles it had organized specifically for desert warfare.

That’s not because Chief Warrant Officer Walter S. Craft, a 57-year-old Lifer and an ardent motorcycle enthusiast with a special love affair for Harley-Davidsons, didn’t try.

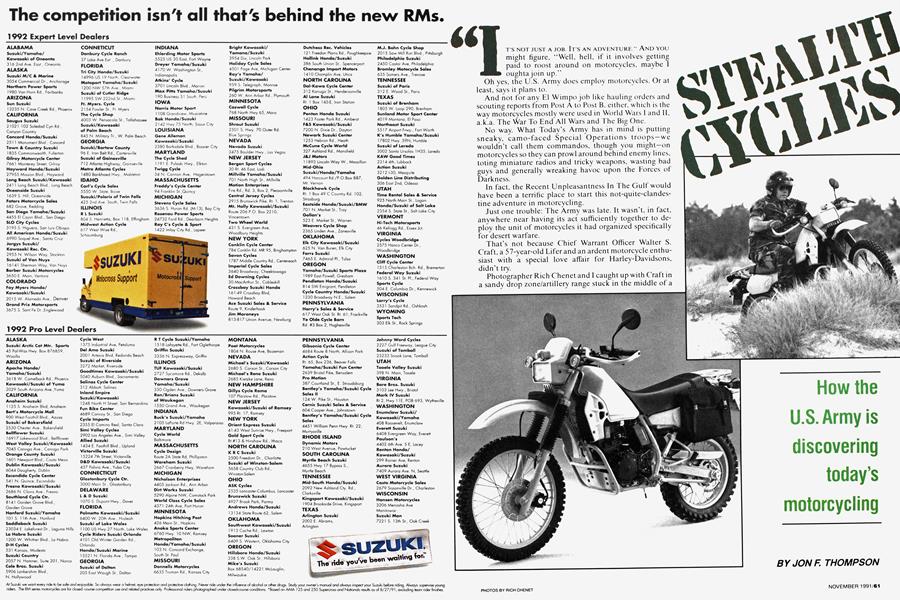

Photographer Rich Chenet and I caught up with Craft in a sandy drop zone/artillery range stuck in the middle of a tropical wilderness called Fort Bragg, just outside Fayetteville, North Carolina. It’s 92 degrees and raining; 90mm howitzers blast away from a camouflaged emplacement to our right, shells whistle over our heads, the deadly rattle of heavy machine guns punctuates our conversation.

How the U.S. Army is discovering today's motorcycling

JON F. THOMPSON

“That’s the sound of stuff that can hurt you,’’ nervously muses Sgt. Jeff Mitchell, the Army public affairs supervisor we're working with on this story. Chenet gets a worried look on his face and asks me, more than half-seriously, “Hey, what about hazard pay for this assignment?’’

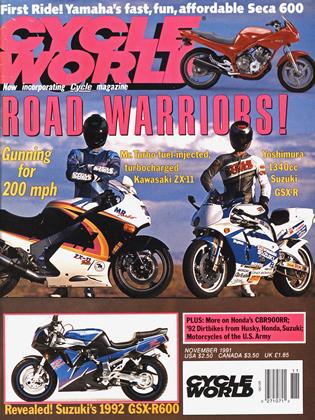

Finding the one man in This Man's Army who is responsible for its Stealth Cycles hasn’t been easy. It took telephone calls to just about every single person with an office in the Pentagon. Through those calls we learned that several other branches of the military employ motorcycles for such uses as forward observation of air strikes and first aid care. But the thought of specially trained Special Operations experts sneaking around behind enemy lines on quiet, camouflaged Kawasakis was just too good to ignore. That was the story we wanted.

It wasn’t exactly the story we got.

Craft doesn’t look his 57 years, but he certainly looks Army, with his head of closely-cropped hair, ramrod posture and a stumpy body as hard as an artillery shell.

He is a 24-year Army veteran and engineer whose specialty is what he calls “heavy junk,’’ the name he’s attached to construction machinery.

“With my knowledge of equipment, I just kinda transitioned into this,’’ he says of the Army’s project to prepare a group of Kawasaki KLR250s for warfare, and to prepare a group of Special Ops soldiers to ride them.

The little KLRs, with their desert-tan paint and blackout lights, were obtained through Hayes Diversified Technologies, in Hesperia, California, for $3000 per unit, a scant $51 above the stock bike’s retail purchase price. “I think you can assume a substantial discount when you buy a number of these,” Fred Hayes, the man behind Diversified Technologies, explains, though he won't say just how many he’s sold to the Army. And the Army won't say how many it has purchased.

The bikes, whatever their number, are intended to operate as part of what’s called the Desert Mobility Vehicle System, or DMVS, organized to meet the needs of 12-man Special Forces units called A-Teams. A DMVS is nothing more complicated than a Hum Vee towing a trailer loaded with a KLR and other gear each team is likely to need. The system’s mission. Craft says in his best Army-speak, is to “increase mobility and the range of operations.”

Okay, but what is it these teams do, exactly, and what is it they'll be using their KLRs for?

Says Craft, looking nervous, “I’m not at liberty to describe the mission. Special Forces missions just aren’t made public. I just can't go into detail.”

Later, he loosens up a little and explains that the DMVS system is set up so it can be parachuted behind enemy lines, snapped out of its harness the instant it hits the ground, and put to work by its A-Team operators, who will range from what he calls an “operational base.”

Our discussion turns to how motorcycles might be detected by ground radar and infrared sensors, and Sgt. Mitchell, the public affairs supervisor, helps us out with an important clue to the bikes' intended use: “We have nets that diffuse the infrared,” he says. Then he adds, “But you’re not gonna see or hear these guys. They’re just gonna be on you.”

Captain Anthony Garcia, a Special Forces officer with a dangerous smile who is here to explain to us the Special Forces organizational hierarchy, helps out. A-Teams, he says, come six to a company, each team composed of an officer, an NCO who is a weapons specialist, two engineers, two medical specialists, two communications specialists, two intelligence-types and two team sergeants. To qualify for an A-Team assignment, each man has undergone from 24 to 55 weeks of special training, depending on his specialty.

Which of them gets the bike and the Bell open-face street helmet that comes with it? Depends on the mission, Craft says. What does the rider take with him? Depends on the mission. Craft says again. So, okay, what might a rider take with him? A compact radio and nothing much heavier than light firearms, Craft finally says. Special Forces guys are naturals for this deal for two reasons: First, they are by nature risk-takers who skydive and SC UBA f or recreation. Second, most of them already own and ride motorcycles. That fact hasn't stopped the Army from calling for special motorcycle training for ATeam members, three kinds of it. First, there's maintenance training that teaches the men how to keep the bikes running. Second, there will be basic rider training, which might eventually be conducted by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. Finally, there will be training designed to teach an experienced rider to negotiate hazards and obstacles while getting from here to there and back.

“Nobody's gonna take these guys and teach them to ride a KLR250 like it was a supercross bike,” says Hayes, the Army's civilian motorcycling contact. “It'll be more like enduro training, not geared towards high speeds, but towards maximum efficiency in negotiating terrain, considering the mission and payload.” Though some mechanical training already has taken place, Hayes adds that specifics of the rider training remain under negotiation.

None of which bothered the U.S. Army when hostilities broke out in the Gulf. It had motorcycles and it had Chief Craft, so it loaded 20 of the bikes aboard a transport airplane and shipped the load to what Craft calls “Sawdi.”

Craft explains what happened next: “We got outta the chute late. The bikes were not deployed as a system.”

They were not deployed, he explains, because once on the ground in Saudi Arabia, the Army had no way to get the bikes out to the individual A-Teams they were destined for. The Army’s supply lines were extremely busy organizing shipment of more essential materiel to the front lines. Craft says.

“We’re also reluctant to introduce new pieces of equipment during hostilities,” added Mitchell.

But with hostilities over, the bikes still haven’t been introduced, in part because the specifics of the training program have not been settled on.

None of this stopped Craft, billed as the Army's leading motorcycle expert, from putting about 600 miles on his KLR in Saudi Arabia, and it doesn’t stop him from cruising carefully around in this sandy drop zone once the rain stops. He’s relaxed and completely unaffected by the whistle of artillery shells overhead, and by the muffled CRUMP those shells make as they find their targets downrange. Ignoring that sound and its implied threat. Craft is displaying the competence of the combat KLR, as he follows the orders barked at him by Chenet, who is trying to rescue what has developed into a not-very photogenic assignment by grabbing a few exposures of Craft at speed. The Chief looks tough enough to intimidate any motorcycle into doing what he wants it to do, but in truth, out in front of Chenet’s rapid-fire Canon, it’s evident Craft is not going to win any enduro championships.

Breathing hard, he manhandles the KLR around, over and through the tufts of grass that have managed to poke up through the sand dunes, pausing frequently to restart it after he kills the engine on photo-pass turnarounds. Sand and bike soon have him whipped.

Craft may not have gotten to deliver his KLRs to the ATeam killers during the 60 days he was posted in Saudi Arabia, but the Special Ops guys will get their bikes. The deal likely will go down without Craft, however. He’s due for a transfer to Korea.

What will happen when the A-Teams get their scoots? Who knows? This last time, pacifist Japan took a lot of flak because the size of its participation in the conflict didn't match U.S. expectations. Maybe next time—if there is a next time—one of that island nation’s better-known products will assist squads of specially trained soldiers as they do their parts to roost to victory.

ft might be kind of like a Saturday night at the supercross. Except the fireworks will be live. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Norton Girl And Other Tragedies

November 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeNone Dare Call It Progress

November 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsReplacements

November 1991 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUpheavals

November 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1991 -

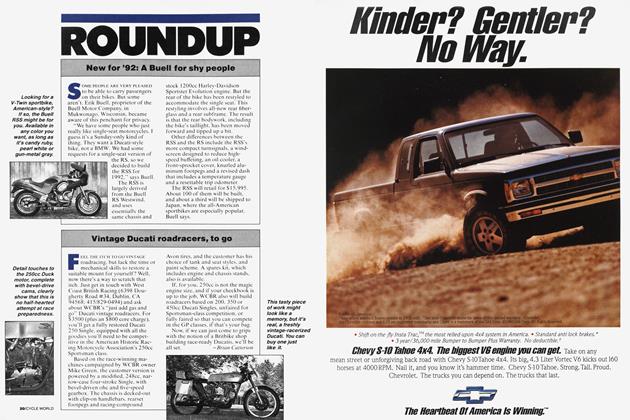

Roundup

RoundupNew For '92: A Buell For Shy People

November 1991