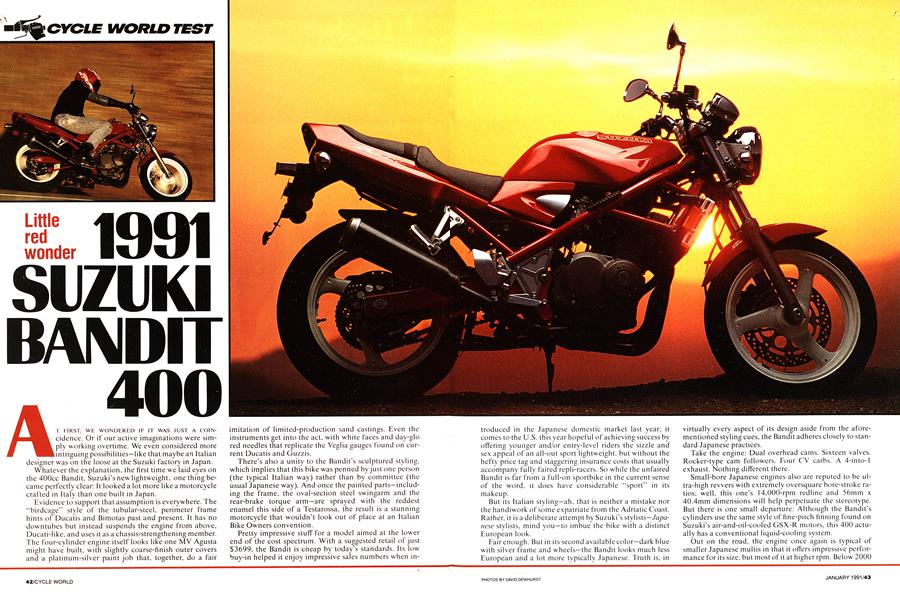

Little red wonder 1991 SUZUKI BANDIT 400

CYCLE WORLD TEST

AT FIRST, WE WONDERED IF IT WAS JUST A COINcidence. Or if our active imaginations were simply working overtime. We even considered more intriguing possibilities—like that maybe an Italian designer was on the loose at the Suzuki factory in Japan.

Whatever the explanation, the first time we laid eyes on the 400cc Bandit. Suzuki’s new lightweight, one thing became perfectly clear: It looked a lot more like a motorcycle crafted in Italy than one built in Japan.

Evidence to support that assumption is everywhere. The “birdcage” style of the tubular-steel, perimeter frame hints of Ducatis and Bimotas past and present. It has no downtubes but instead suspends the engine from above, Ducati-like, and uses it as a chassis-strengthening member. The four-cylinder engine itself looks like one MV Agusta might have built, with slightly coarse-finish outer covers and a platinum-silver paint job that, together, do a fair imitation of limited-production sand castings. Even the instruments get into the act, with white faces and day-glo red needles that replicate the Veglia gauges found on current Ducatis and Guzzis.

There’s also a unity to the Bandit’s sculptured styling, which implies that this bike was penned by just one person (the typical Italian way) rather than by committee (the usual Japanese way). And once the painted parts—including the frame, the oval-section steel swingarm and the rear-brake torque arm—are sprayed with the reddest enamel this side of a Testarossa, the result is a stunning motorcycle that wouldn’t look out of place at an Italian Bike Owners convention.

Pretty impressive stuff for a model aimed at the lower end of the cost spectrum. With a suggested retail of just $3699, the Bandit is cheap by today’s standards. Its low buy-in helped it enjoy impressive sales numbers when introduced in the Japanese domestic market last year; it comes to the U.S. this year hopeful of achieving success by offering younger and/or entry-level riders the sizzle and sex appeal of an all-out sport lightweight, but without the hefty price tag and staggering insurance costs that usually accompany fully faired repli-racers. So while the unfaired Bandit is far from a full-on sportbike in the current sense of the word, it does have considerable “sport” in its makeup.

But its Italian styling—ah, that is neither a mistake nor the handiwork of some expatriate from the Adriatic Coast. Rather, it is a deliberate attempt by Suzuki's stylists—Japanese siyWsis, mind you —to imbue the bike with a distinct European look.

Fair enough. But in its second available color—dark blue with silver frame and wheels—the Bandit looks much less European and a lot more typically Japanese. Truth is, in virtually every aspect of its design aside from the aforementioned styling cues, the Bandit adheres closely to standard Japanese practices.

Take the engine: Dual overhead cams. Sixteen valves. Rocker-type cam followers. Four CV carbs. A 4-in to-1 exhaust. Nothing different there.

Small-bore Japanese engines also are reputed to be ultra-high revvers with extremely oversquare bore-stroke ratios; well, this one’s 14,0()0-rpm redline and 56mm x 40.4mm dimensions will help perpetuate the stereotype. But there is one small departure: Although the Bandit’s cylinders use the same style of fine-pitch finning found on Suzuki’s air-and-oil-cooled GSX-R motors, this 400 actually has a conventional liquid-cooling system.

Out on the road, the engine once again is typical of smaller Japanese multis in that it offers impressive performance for its size, but most of it at higher rpm. Below 2000 or 2500 rpm, the Bandit won’t accelerate at all; the engine has to be spinning closer to 3000 rpm for anything to happen when the throttle is opened. But from there up to about 8000, it begins pulling half-decently. And from 8000 to the 14-grand redline, the power is potent for a 400.

Want evidence? Our Bandit ran the quarter-mile in 12.99 seconds at 101.01 mph—0.17 second quicker (but 1.14 mph slower in terminal speed) than the Honda CB-1 400 we tested this past July. The Honda perhaps made a tad more power on the top end, but it also had a slightly peakier powerband and, seemingly, marginally less midrange. By comparison, the Suzuki’s power output between 3000 and 14,000 rpm increases almost linearly in accordance with engine speed.

For most kinds of riding, the Bandit has more than adequate power; after all, even most 650s of just 10 years ago weren’t capable of high-12-second quarter-mile ETs. Making quick passes on the highway, however, calls for between one and three downshifts, since acceleration in sixth gear at most legal speeds is not very forceful.

Still, when ridden aggressively, the Bandit can unravel a twisty backroad in spectacular and impressive fashion. You need to play a constant tap-dance with the slick-shifting, six-speed gearbox to keep the engine from slipping below the 8000-rpm mark; and if you’re looking for maximum acceleration between turns, plan on spending most of your time making unbelievable rpm noises in the 10,000-to-14,000 zone. You’ll also get the most from your backroad blitzes if you scrub offas little speed as possible through the turns; as with all smaller Japanese Multis, every mile per hour you lose in a corner on the Bandit takes a lot of time to regain on the ensuing straightaway.

Fortunately, the Bandit’s handling allows this “use it or lose it” cornering-speed concept to be a lot of fun. The chassis is extremely responsive, due to the bike's light weight (393 pounds dry), rather short (56.3-inch) wheelbase and quick steering geometry (25.5 degrees of rake, 3.9 inches of trail). Plus, the fairly high and wide handlebar gives the rider lots of steering leverage. So, little effort is needed to flick the Bandit over into a turn or snake it through a series of fast esses.

Once heeled over, the Suzuki zips around turns like an oversized slot car. The steering remains perfectly neutral, the chassis allows uneventful mid-corner line changes, and the wide (110 front. 150 rear), 17-inch bias-ply tires stick really well at street-cornering speeds. No undercarriage bits ever drag, and the suspension copes nicely with surface undulations that could upset the bike's comforting stability at radical lean angles. Even the single-disc brakes at both ends perform impeccably, never fading or losing their feel in the face of repeated backroad abuse.

What results from this engine and handling combination is a bike that makes you feel like a roadrace hero. You have to work a bit harder than usual to carve up the twisties, but the Bandit rewards your efforts manyfold in pure fun and exhilaration.

Too bad we can’t give such high marks to the ride, which is firm enough to impose tight limits on the length of your trips. The ride is acceptable on smaller bumps and ripples; but when the Bandit whomps over bigger bumps, it delivers the brunt of those blows directly to the rider’s posterior.

Some of the blame can be put on the suspension, which is on the taut side, especially at the rear. But most of the ride harshness can be traced to the seat. The front half of the stylish, two-piece seat is too thin and narrow to isolate the rider from impacts that are big enough to foil the suspension. Even after a couple of hours of travel on perfectly smooth roads, a Bandit rider—or passenger, whose accommodations are even more Spartan—welcomes any reason whatsoever to stop and relieve the painful numbbutt that has set in.

Otherwise, the Bandit’s ergonomics aren’t bad for a machine of its type and size. Granted, the high, rearset footpegs force a tight, roadracy bend in the knees that taller riders can find bothersome. But regardless of a rider’s size, the tubular handlebar locates the grips high enough to put his or her torso in an extremely rational, almost upright riding position, one that remains comfortable no matter how long the ride. Vibration isn’t a big problem, either, since the strongest buzzes—which even at their worst aren’t debilitating—don’t come into play until 8000 rpm (about 75 mph) and above.

Still, there’s no way to sidestep the fact that the Bandit has a few ergonomic shortcomings. But to a large extent, that drawback is offset by another, more positive fact; This is one exciting motorcycle to ride. On a tight, curvy ribbon of road that folds around on itself mile after mile, the Bandit is about as much pure fun as anyone can possibly stand.

That’s why we see the Bandit as a two-wheeled equivalent of one of today’s most successful automobiles, the Mazda Miata: Both machines are simple, inexpensive, attractively styled to have European appeal, and sporty in a way that recalls an earlier, less complicated age of motoring. And best of all, both are a real hoot when you’re intent on straightening out every corner in the state.

Even if neither one was designed by an Italian. E)

SUZUKI BANDIT 400

$3699

American Suzuki Motor Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Meet the Nicest People...

January 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeLegacy of the Hustler

January 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Gold Wing From Red Wing

January 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupEuro-Enduros: the Rally Rage Rolls On

January 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's New Approach: Buy A Bike, Get Insurance As Part of the Package

January 1991 By Jon F. Thompson