NEW LIFE FOR AN OLD BIKE

CW PROJECT

Upgrading the usefulness of an 8-year-old Suzuki

JUDGING FROM THE STATE OF NEW STREET-BIKE sales, a significant number of us remain happy with the bikes we already possess. But few riders remain truly satisfied with a given level of performance. There is fast, you see, and then there is faster, and the latter always is better than the former, especially if the injection of performance doesn't degrade reliability or practicality.

The question frequently forwarded to these offices, therefore, is, “How can I modify my bike so that it will run and handle like the new ones?”

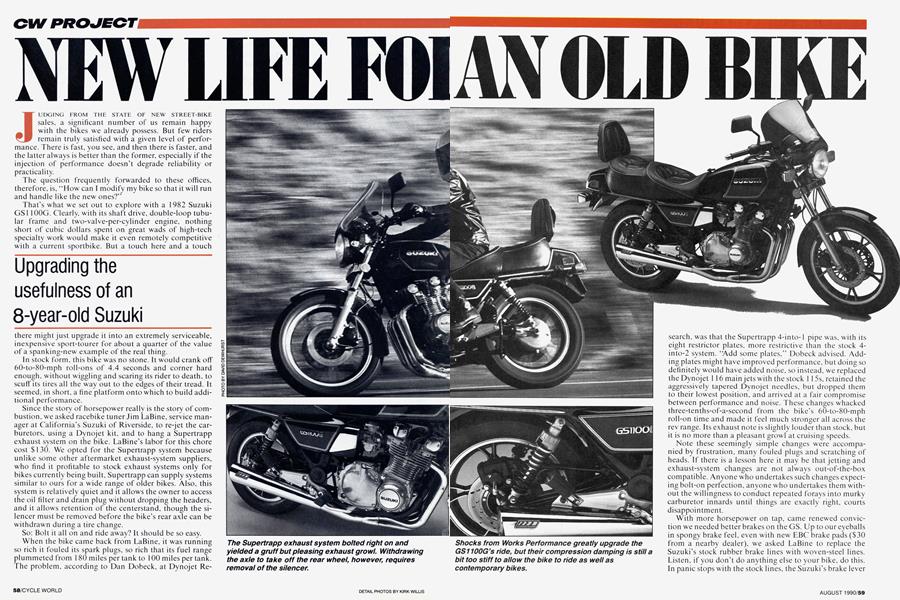

That’s what we set out to explore with a 1982 Suzuki GSI 100G. Clearly, with its shaft drive, double-loop tubular frame and two-valve-per-cylinder engine, nothing short of cubic dollars spent on great wads of high-tech specialty work would make it even remotely competitive with a current sportbike. But a touch here and a touch

there might just upgrade it into an extremely serviceable, inexpensive sport-tourer for about a quarter of the value of a spanking-new example of the real thing.

In stock form, this bike was no stone. It would crank off 60-to-80-mph roll-ons of 4.4 seconds and corner hard enough, without wiggling and scaring its rider to death, to scuff its tires all the way out to the edges of their tread. It seemed, in short, a fine platform onto which to build additional performance.

Since the story of horsepower really is the story of combustion, we asked racebike tuner Jim LaBine, service manager at California’s Suzuki of Riverside, to re-jet the carburetors, using a Dynojet kit, and to hang a Supertrapp exhaust system on the bike. LaBine’s labor for this chore cost $ 130. We opted for the Supertrapp system because unlike some other aftermarket exhaust-system suppliers, who find it profitable to stock exhaust systems only for bikes currently being built. Supertrapp can supply systems similar to ours for a wide range of older bikes. Also, this system is relatively quiet and it allows the owner to access the oil filter and drain plug without dropping the headers, and it allows retention of the centerstand, though the silencer must be removed before the bike’s rear axle can be withdrawn during a tire change.

So: Bolt it all on and ride away? It should be so easy.

When the bike came back from LaBine, it was running so rich it fouled its spark plugs, so rich that its fuel range plummeted from 180 miles per tank to 100 miles per tank. The problem, according to Dan Dobeck, at Dynojet Research, was that the Supertrapp 4-into-l pipe was, with its eight restrictor plates, more restrictive than the stock 4into-2 system. “Add some plates,” Dobeck advised. Adding plates might have improved performance, but doing so definitely would have added noise, so instead, we replaced the Dynojet l 16 main jets with the stock l l 5s, retained the aggressively tapered Dynojet needles, but dropped them to their lowest position, and arrived at a fair compromise between performance and noise. These changes whacked three-tenths-of-a-second from the bike’s 60-to-80-mph roll-on time and made it feel much stronger all across the rev range. Its exhaust note is slightly louder than stock, but it is no more than a pleasant growl at cruising speeds.

Note these seemingly simple changes were accompanied by frustration, many fouled plugs and scratching of heads. If there is a lesson here it may be that jetting and exhaust-system changes are not always out-of-the-box compatible. Anyone who undertakes such changes expecting bolt-on perfection, anyone who undertakes them without the willingness to conduct repeated forays into murky carburetor innards until things are exactly right, courts disappointment.

With more horsepower on tap, came renewed conviction we needed better brakes on the GS. Up to our eyeballs in spongy brake feel, even with new EBC brake pads ($30 from a nearby dealer), we asked LaBine to replace the Suzuki’s stock rubber brake lines with woven-steel lines. Listen, if you don’t do anything else to your bike, do this. In panic stops with the stock lines, the Suzuki’s brake lever would come back to the handlebar. Now, a squeeze on the lever just stops the bike, period. The price tag for parts and installation was $ 1 90—it can be done for a lot less money, we’ve learned—but the result was good for our confidence, not to mention our post-commute state of mind.

The goal of improved performance taken care of, attention was turned to handling, looks and comfort. This Suzuki was wearing its original shocks, which were tired, so we replaced them with a pair built by Works Performance. A significant improvement here, with much smoother, more-compliant movement throughout the rear suspension’s limited range of movement, though because of the way the shocks are valved, they retained the stock shocks' harshness over abrupt, square-edged surface irregularities.

Installed along with the shocks was a pair of Dunlop K491 tires, which in our experience offer a satisfactory compromise between long wear and sticky grip, though if you’re really interested in hanging with modern machinery, an investment in stickier rubber, say Dunlop K591s, would be a good move.

Rider and passenger both felt the irregularities passed to the chassis through the shocks and tires, so wisdom dictated upgrading the bike’s seat. The stocker had been replaced with a double-bucket touring model, which besides being not particularly sporting in appearance, was only marginally more comfortable than the stock seat. So this was replaced with one of Mike Corbin’s excellent BMWstyle touring saddles and matching backrest. This seat easily has been one of the most-comfortable seats we’ve experienced. Our passengers like it, too, though some preferred the bike's previous high backrest to the lower Corbin unit.

Upgrading the Suzuki's windscreen proved nearly as frustrating as effecting the required jetting changes. The bike came into our hands wearing a National Cycle Plexifairing 3, which retails for $140. It worked, but seemed deficient in style. So we ordered a Saeng QS2 fairing. Unfortunately, this worked no better than the Plexifairing, was almost three times as expensive and at least three times as difficult to install. Additionally, where the Plexifairing delivered slight oscillations while cornering at high speeds, the Saeng delivered more-disturbing oscillations at those same speeds. Notified of these deficiencies, Saeng owner Chuck Saunders expressed dimay and offered to send us a QS2 for another model of motorcycle. At this time, we’re evaluating one on a BMW K75. We'll report on that in a future issue.

In any event, off came the QS2, replaced with a National Cycle “Agressor”(yep, we know that’s misspelled, tell National Cycle), mounted to a black K&N Daytona Touring handlebar that we picked up at a local dealership for $29. This yielded roughly the same degree of upperbody protection as the fairings on most modern sportbikes, which is what we wanted in the first place. It isn’t overly attractive, but it works. As Mom used to say, “Pretty is as pretty does.”

And that brings us to the bottom line: Is this motorcycle now the equal of a contemporary sporting mount? In a word, no. But it is greatly improved, and the cost of those improvements, when weighed against the cost of a new bike, make the exercise worth the effort. gg

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1990 -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson