SIMPLY THE BEST

RACE WATCH

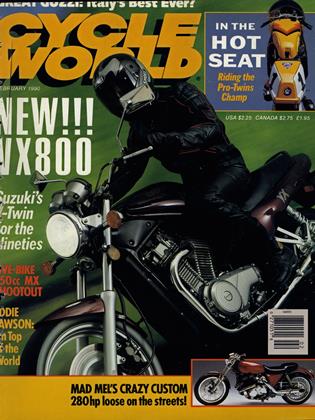

The European press calls Eddie Lawson arrogant and aloof; everyone else calls him the greatest roadracer in the world

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

FOLLOWING THE ROAD OUT OF town and up toward the mountains. I begin to get a better feel for four-time Grand Prix World Champion Eddie Lawson. He has backed himself up against California’s San Gabriel Mountains, living in a large, ranch-style house set near the top of a small canyon overlooking a desert valley. It reminds me of Cochise's hideout.

The house itself is impressive, from the entrance foyer with its cathedral ceilings to the unexpected, pearl-white, baby-grand piano. But I'm surprised most by the silence, church-like and heavy, in a house protected from the demands of ringing phones by a constantly changing number known only to family and Lawson's closest friends. After a tumultuous race season spent in air-planes, motor homes and rental cars. traipsing from Japan to Australia to the U.S. to Europe to South America, this is the calm that Lawson retreats to before heading into another season of testing, training and racing.

This year, after winning the 500cc world roadracing championship for the second year in a row, a feat unequaled since Kenny Roberts won three consecutive championships starting in 1978, Lawson deserves more rest than before. Because of his well-publicized switch—some said defection—last season from Marlboro-sponsored Yamahas to Rothmans Hondas, Lawson had to campaign harder than he ever had previously to stay on top. That he won his fourth championship while riding for a new team and on an unfamiliar bike, all the while under the microscope of some of the most-intense media scrutiny he had ever faced, adds evidence to the belief more and more people are turning to: Eddie Lawson may well be the greatest motorcycle racer of all time.

And now. Lawson has once again stirred up the GP world by packing his number-one plate off to a new team. He has signed to ride the 1990 season for Kenny Roberts’ team alongside Wayne Rainey. The team will run Yamahas, but has dropped its Lucky Strike sponsorship and will campaign instead in the fluorescentred-and-white Team Marlboro colors.

Lawson, who rode Yamahas for six years prior to his unexpected changeover to Hondas, is no longer concerned by the uncertainties associated with riding for a new team. “I have no loyalty to the Japanese companies.” he says. “My loyalty goes to the teams and the people 1 work with on a day-to-day basis. Last year, people w'rote me off even before I rode the bike. They said I'd never be able to ride for Honda. But I did.”

But even Lawson admits he had some doubts when his 1989 season got off to a sputtering start. Just a few days before the first GP of the year in Japan, he fell in practice, breaking his wrist and hurting his back. Still, he managed a third-place finish in the race.

Then things almost slipped away from Lawson when, during practice for the very next race, held in Australia, Kevin Magee’s Yamaha seized its engine right in front of him. T he two collided and Lawson went down. “That crash really beat me up.” recalls Lawson. “My whole body hurt from being so banged up.” The crash was bad enough in itself, but hardest to swallow was the criticism that came after he had struggled to a fifthplace finish in the race.

“No one seems to remember that I was hurt for those first races,” Lawson says. “They said. ‘Eddie seems tense.’ Or, ‘Eddie isn't riding like he should.’ Hey, the truth was. I was hurt.”

Those seemingly unfair reviews of his riding in Australia point out what has been a persistent thorn in Lawson's side: his distant relations with the press. For the first part of the 1989 season, he consistently finished second or third, but the European press, he says, kept blasting him for having such a terrible season.

“I had two bad races in the beginning, but I'm still close in points, so why am I having a ‘terrible season.' I wondered? I didn't understand it,” he says softly. Lawson then pauses, gets up. opens a window and gazes outside. It’s obvious that his poor standing with some reporters bothers him. and that he thinks he’s been given a bad rap.

Lawson believes his difficulty with the press stems from his very first season in Europe. 1983. He was being groomed as the replacement for soon-to-retire Kenny Roberts, but Lawson remained in the background as Roberts and Freddie Spencer battled titanically, trading race wins and garnering all the headlines that year. Also, Lawson, then 24, was still learning the ropes, and, being rather shy, he was intimidated by the brash, outspoken Roberts and the polished, corporate Spencer.

“1 didn't know anybody when 1 first went to Europe,” he says. “It’s just my character to take a while to warm up to someone, and the press wasn't happy that I didn't talk.”

Lawson soon was saddled with the reputation of being a loner, a kind of solitary mystery man, aloof and arrogant. That, Lawson thinks, came from a basic misunderstanding of his character.

“At the races, I'm concentrating on what I have to do, so sometimes I’ll walk right by someone I know and never even see them. Because I'm focused on my job. people think I'm unapproachable, and some even write stories and never even bother to talk to me. That's the worst,” he says.

With his 1989 season ofT to a lessthan-auspicious start, and his ongoing feud with the GP press, Lawson could have easily gone into a tailspin. That didn't happen, thanks to Lawson’s never-say-die attitude and to the buoyant spirit of Rothmans crew chief Irv Kanemoto, the super-tuner who was instrumental in the successes of both Gary Nixon and Freddie Spencer.

“Irv was the guy who made it happen,” Lawson says emphatically. “No matter how hard I worked, Irv and the rest of the guys worked harder. When I was down at the start, they worked even harder to make it easy on me. It’s so difficult to stay mentally on top of things when you are physically down and the bike isn’t working, but when I saw how much effort the team was putting into it. I felt encouraged like I never have before.”

Lawson’s new boss, Kenny Roberts, certainly knows the importance of good teamwork, but thinks Lawson should take more of the credit for the 1989 title. “Eddie has always had his head in the right place to be a champion,” says Roberts, “but last year, he found his heart, and put them together. That makes him even harder to beat.”

Just how much longer Lawson’s head and heart will allow him to remain at the top of the grand prix world—long enough, perhaps, to surpass the eight titles of all-time 500cc championship winner Giacomo Agostini — is up to Lawson. There has been talk of a jump to automobile racing. But, for now. despite all the pressures, Eddie Lawson, four-time U.S. national champion, four-time world champion, will remain where he’s at his best: on two wheels.

“Everything is great when I'm on the bike,” he says. “I love to race, and I still want to win every race I enter.”s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

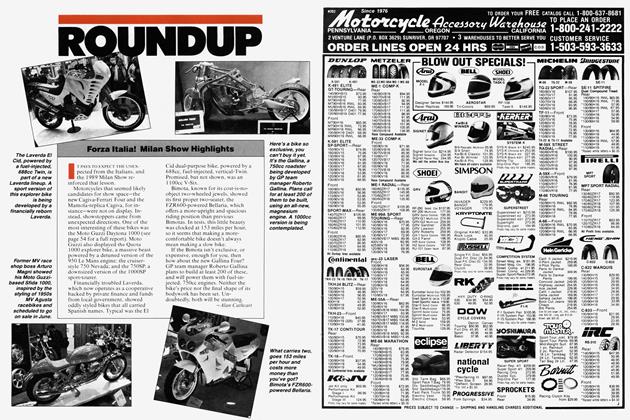

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990