RIDING WITH DISPATCH

You don't have to be a mad dog or an Englishman to be the world's best motorcycle messenger. But it helps.

ROLAND BROWN

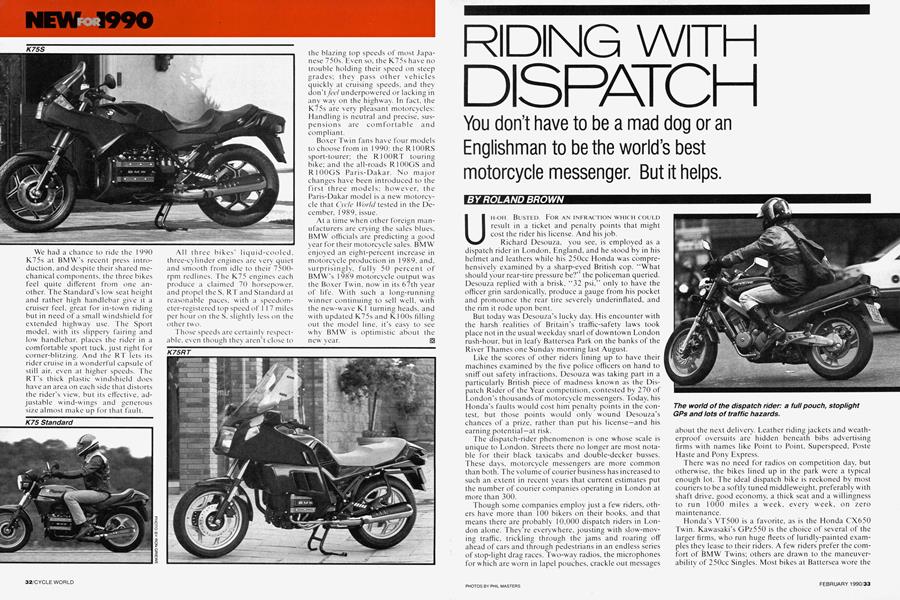

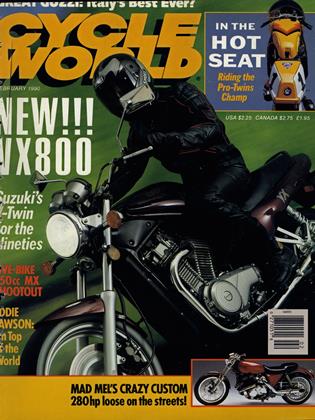

UH-OH. BUSTED. FOR AN INFRACTION WHICH COULD result in a ticket and penalty points that might cost the rider his license. And his job.

Richard Desouza, you see, is employed as a dispatch rider in London, England, and he stood by in his helmet and leathers while his 250cc Honda was comprehensively examined by a sharp-eyed British cop. “What should your rear-tire pressure be?” the policeman queried. Desouza replied with a brisk, “32 psi,” only to have the officer grin sardonically, produce a gauge from his pocket and pronounce the rear tire severely underinflated, and the rim it rode upon bent.

But today was Desouza’s lucky day. His encounter with the harsh realities of Britain’s traffic-safety laws took place not in the usual weekday snarl of downtown London rush-hour, but in leafy Battersea Park on the banks of the River Thames one Sunday morning last August.

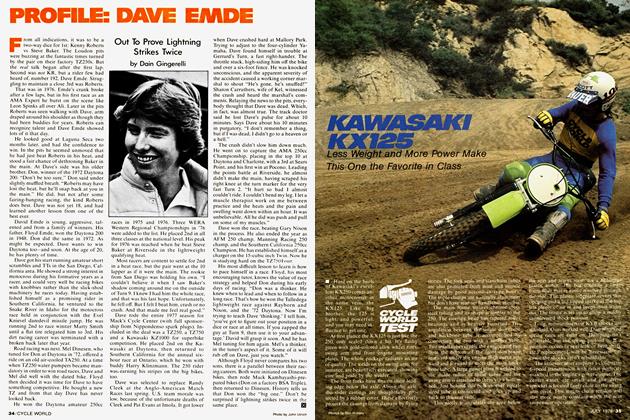

Like the scores of other riders lining up to have their machines examined by the five police officers on hand to sniff out safety infractions, Desouza was taking part in a particularly British piece of madness known as the Dispatch Rider of the Year competition, contested by 270 of London’s thousands of motorcycle messengers. Today, his Honda’s faults would cost him penalty points in the contest. but those points would only wound Desouza’s chances of a prize, rather than put his license—and his earning potential—at risk.

The dispatch-rider phenomenon is one whose scale is unique to London. Streets there no longer are most notable for their black taxicabs and double-decker busses. These days, motorcycle messengers are more common than both. The volume of courier business has increased to such an extent in recent years that current estimates put the number of courier companies operating in London at more than 300.

Though some companies employ just a few riders, others have more than 100 bikers on their books, and that means there are probably 10,000 dispatch riders in London alone. They’re everywhere, jousting with slow-moving traffic, trickling through the jams and roaring off ahead of cars and through pedestrians in an endless series of stop-light drag races. Two-way radios, the microphones for which are worn in lapel pouches, crackle out messages about the next delivery. Leather riding jackets and weatherproof oversuits are hidden beneath bibs advertising firms with names like Point to Point, Superspeed. Poste Haste and Pony Express.

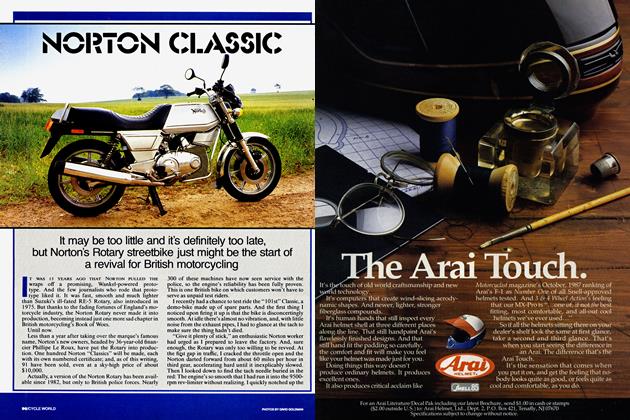

There was no need for radios on competition day, but otherwise, the bikes lined up in the park were a typical enough lot. The ideal dispatch bike is reckoned by most couriers to be a softly tuned middleweight, preferably with shaft drive, good economy, a thick seat and a willingness to run 1000 miles a week, every week, on zero maintenance.

Honda’s VT500 is a favorite, as is the Honda CX650 Twin. Kawasaki’s GPz550 is the choice of several of the larger firms, who run huge fleets of luridly-painted examples they lease to their riders. A few riders prefer the comfort of BMW Twins; others are drawn to the maneuverability of 250cc Singles. Most bikes at Battersea wore the equipment of the trade: plastic sideand top boxes, the better to protect parcels and letters.

After the mandatory safety check, things got serious. Riders disappeared into a large, striped tent for a written exam that tested knowledge of London’s incredibly confusing street layout and of the Highway Code, the British government's guide to good driving. Then, it was on to the bike-control test, where riders had to slalom around a series of tightlv placed cones and, at one point, ride the length of a wooden plank.

Some had the riding test wired, flicking between the cones with a blip of throttle here, a dab of back brake there, to score 100 points for a perfect round. Others were less lucky, brushing cones, ham-fistedly grabbing the front brake to set their "forks plunging, and losing marks w ith every steadying dab of toot on ground.

Unluckiest of all was Peter Leeper, a Honda VT rider w ho fell afoul of an unwitting piece of competition realism when his front tire went flat after communing with a nail in the plank.

Leeper. an actor by profession, is typical of many dispatch riders who use the job's freedom (most are selfemployed, and paid a percentage of each delivery charge) to supplement other occupations.

“Dispatching is ideal for me,” he said, cheerful in spite of his puncture, his wavy, dark hair contrasting with the windings of a w hite silk scarf around his neck. “I enjoy it. It pays well, and you can take time off whenever you like. If some acting w ork comes along, I do that; if not. 1 know I can turn to dispatching and earn enough to keep me going.”

But others are less keen. “I don’t like dispatching, but you get trapped in it.” said Martin Shaw, a 26-year-old part-time photographer leaning a leather-jacketed elbow' on his scruffy, "l 76,000-mile Honda CB250 (“I don't change the oif. I just keep filling it up.”). “I thought I’d be doing it for six months, but after six years I'm still here. 1 work just three days a week and don t start til 1 1 a.m., but I can still make 50 or 60 pounds (S80-S95) a day. 1 hat gives me the freedom to do other things the rest of the time.”

Another RS250 rider. Joe Tracey, had the opposite view. A married man of 46. he gave up the routine of his office job three years ago to become a dispatch rider and has never regretted it. “1 wish 1 d done this earlier, he said. “I love The life, and I'm earning more now than I was in the office. It's the freedom I like, especially when you get out of town on the open road and can really unwind. There's a good camaraderie, too. Other riders always gi\ e a little wave, and if you ever have an accident, they always descend on you to help.”

Tracey had picked up too many penalty points during the slalom competition to be in contention for a prize, but was enjoying himself nevertheless. Outside the contest s control tent, a board showed the leading scores as the early riders completed the final segment of the dispatch competition, which, like the first "three, offered a total of 100 points. This was a simulated parcel pick-up or delivery, during which, contestants were followed and scored for riding"skill and for the way they behaved in dealing with the all-important client receiving the delivery.

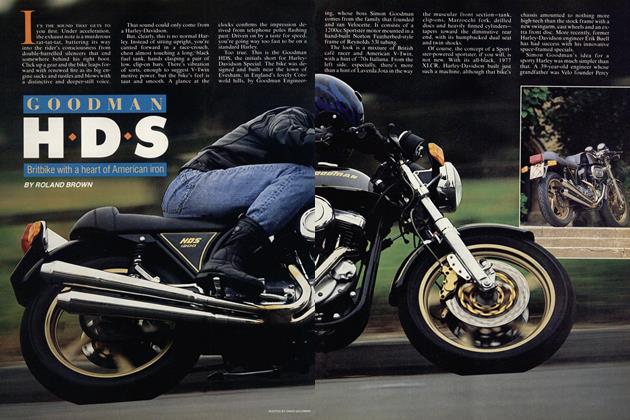

One competitor, a blonde-haired woman in a fringed leather jacket, was about to leave. I trailed the storekeeper's Katana 1 100 as he followed her dayglo-orange Mercury Dispatch Honda from the park. 1 hrough untypically light Sunday traffic she weaved, narrowly avoiding one incident before wriggling between two lines of cars with what looked like a brush of Honda plastic against Ford bodywork.

Past the famous Tate Gallery we headed, eventually stopping near a crossroads in the shadow of Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament. The drop point at a police station was nearby, and while the contestant went inside, her scorekeeper, a handlebar-mustached gent in waxed-cottons and an open-face helmet, delivered his verdict: “She hasn't got a cat's chance in Hell. She’s already clouted a car in a traffic jam, she’s been busting speed limits all over the place and now she’s parked on a yellow line. At this rate, she won't live to be somebody’s mother.”

Lorna Goulden, the luckless rider, did not help her score, a somewhat-generous 70 out of 100. by getting lost on the way back to Battersea Park. But at least she made it back in one piece.

Goulden, her problems in traffic notwithstanding, at least had two years of riding experience, though until two weeks before the contest, when she'd turned to dispatching for vacation money, she'd been a student. Of fargreater concern to British authorities than modestly experienced occasional like Goulden are the large number of unqualified learner dispatch riders who are attracted by unscrupulous firms’ offers of easy money, but who all too often end up under a bus, instead.

“Some of the learners are horrible,” said a policeman, his bike-checking duties over for the day. “I stopped one lad the other day on a Honda 125. Its front brake cable was snapped right through and its fork was badly bent. I persuaded him to park his bike and walk home, but what can you do while the industry employs 17-year-olds who’ve never ridden a bike and who buy one to get the job?” It’s a serious problem for the dispatch trade, whose public image in England is poor. In recent months, a judge has demanded action, and The Times of London has run a fea-

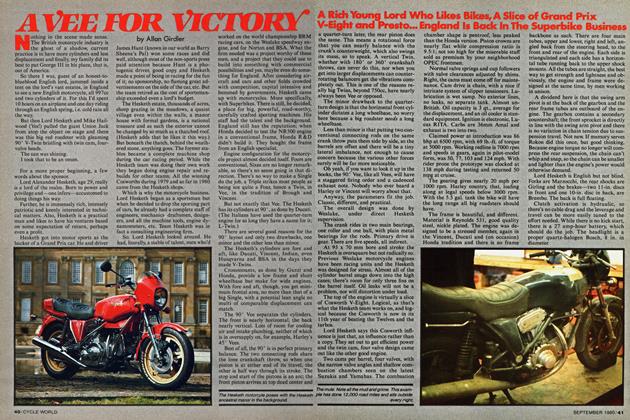

ture on the problem, headlined “Messengers of Danger.” Legislation is likely in the near future; motorcycling in general suffers in the meantime. But not all firms employ learners, and 65 of the more-reputable companies are members of the Dispatch Association, which promoted this safety-oriented Dispatch Rider of the Year contest and financed its grand prize, a new Yamaha XJ600.

As results were posted, groups of riders clustered around the scoreboard to see who would ride the XJ away. The sun sank lower over the Thames, the rock music that had been booming all day reached a crescendo and, after much rechecking of scorecards, 22-year-old north-Londoner Gary Head was awarded the prize with a mark just three points short of a perfect 400.

There was polite applause, a handshake, a couple of photographs, a few' words to the man from the newspaper. And then, considering the XJ less than ideal for dispatching, the winner was busy negotiating to sell the bike back to a dealer. For Gary Head, professional motorcyclist, this had turned out to be just another day at work. SI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

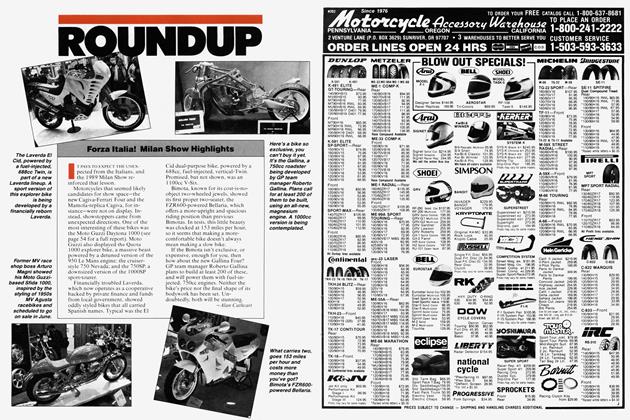

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990