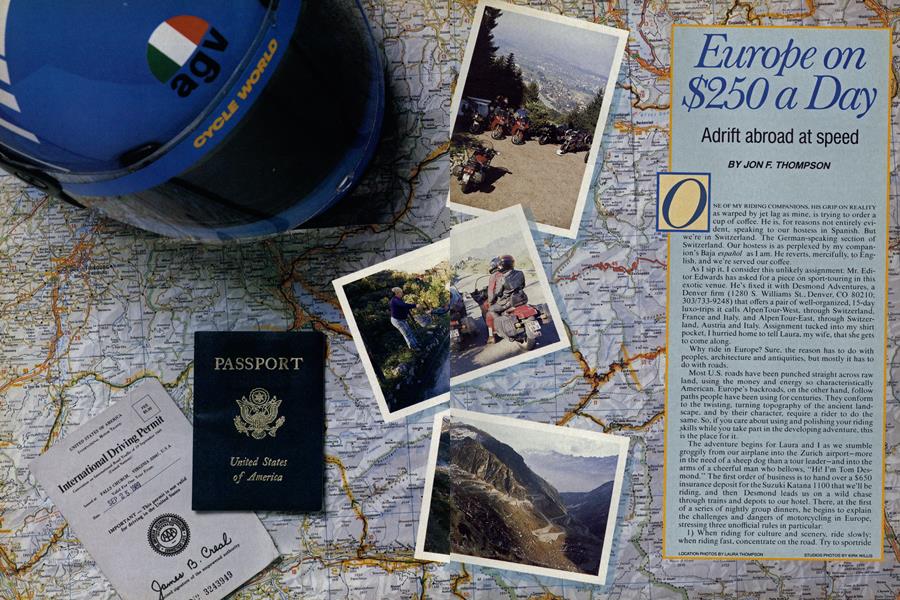

Europe on $250 a Day

Adrift abroad at speed

JON F. THOMPSON

ONE OF MY RIDING COMPANIONS, HIS GRIP ON REALITY as warped by jet lag as mine, is trying to order a cup of coffee. He is, for reasons not entirely evident, speaking to our hostess in Spanish. But we're in Switzerland. The German-speaking section of Switzerland. Our hostess is as perplexed by my companion's Baja español as I am. He reverts, mercifully, to English, and we’re served our coffee.

As I sip it, I consider this unlikely assignment: Mr. Editor Edwards has asked for a piece on sport-touring in this exotic venue. He’s fixed it with Desmond Adventures, a Denver firm (1280 S. Williams St., Denver. CO 80210; 303/733-9248) that offers a pair of well-organized, 15-day luxo-trips it calls AlpenTour-West, through Switzerland, France and Italy, and AlpenTour-East, through Switzerland, Austria and Italy. Assignment tucked into my shirt pocket, I hurried home to tell Laura, my wife, that she gets to come along.

Why ride in Europe? Sure, the reason has to do with peoples, architecture and antiquities, but mostly it has to do with roads.

Most U.S. roads have been punched straight across raw land, using the money and energy so characteristically American. Europe’s backroads, on the other hand, followpaths people have been using for centuries. They conform to the twisting, turning topography of the ancient landscape, and by their character, require a rider to do the same. So, if you care about using and polishing your riding skills while you take part in the developing adventure, this is the place for it.

The adventure begins for Laura and I as we stumble groggily from our airplane into the Zurich airport—more in the need of a sheep dog than a tour leader—and into the arms of a cheerful man who bellows, “Hi! I’m Tom Desmond.” The first order of business is to hand over a $650 insurance deposit for the Suzuki Katana 1 100 that we’ll be riding, and then Desmond leads us on a wild chase through trains and depots to our hotel. There, at the first of a series of nightly group dinners, he begins to explain the challenges and dangers of motorcycling in Europe, stressing three unofficial rules in particular:

1) When riding for culture and scenery, ride slowly; when riding fast, concentrate on the road, fry to sportride with an eyeball cocked for scenery, and you'll crash.

2) Be on the lookout for what Desmond calls “green ice,” the evidence of the passage of thousands of Sw itzerland’s dairy cows, who travel from milking barn to pasture on the very roads we'll be using. This stufi'is very slippery.

3) Watch the speed limits. The coppers here are equipped with radar, automatic weapons and the power either to fine you a billion, on the spot—lifting your passport until you pay—or to instantly remove your right to drive on the highways of their country.

One of our fellow riders, John Benz of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, an AlpenTour repeat customer, is undaunted by Desmond's warnings. “I came here to ride,” he says. “This is riding con brio: there's nothing like it anywhere in the world. Conditions at home don't begin to approach those here.” He pauses a moment, and adds, “You know what this is about? This is about being 12 years old again, maybe 1 5. It's about being bad little boys.”

Benz, here with his brother Fred and several pals, enhances his budding reputation almost immediately by stepping off his rented CBR1000 in an Italian hairpin corner, roaching the bike's fairing, handlebar, footpeg and turnsignal, pretty much toasting his insurance deposit. Later, he fractures the poor Honda’s oil sump w hile on an ill-advised dirt-road excursion. But Benz is only the first: Before the trip is done, 10 of our 24 bikes will go dow n.

For Benz, this trip may be about reverting to Bad-LittleBoyhood, but for me. it’s about the close-curved roads that traverse the rock-and-ice landscape of the Alps. These roads lead us over passes with names like Piccolo St. Bernard, Simplon. Furka and Nufenen. and straight into sportbike heaven. Here are long straights, sharp hairpins and fast sweepers, an entire road-builder’s catalog of corners carved into the harsh, granite flanks of some of Earth's most-spectacular mountains.

Laura and I start the first day with a small group led by Desmond. Concentrating hard and stopping for frequent strudel breaks, we require seven hours to wobble a measly 1 10 miles over three steep, narrow, mountain passes. Along the way. we're startled when some Eurocrazy on a Gold Wing blows past our Katana 1 100 in a set of switchbacks like we're bolted to the pavement. Hey, I’ve been riding as briskly as I dare: it's just that this is, well, a different riding reality than the one I'm used to. By the time we pull into our hotel parking lot in tiny Morschach, high above the eastern shore of Lake Lucerne. Laura and I, still in thegrips of jet lag. are sufficiently tired to begin speaking Baja español ourselves.

Marsha Everett isn't, though she has a right to be. She and Art, her husband, from Scarborough, Maine, crashed on Pragel Pass, a route that is, by U.S. standards, little more than a goat trail some Swiss maniac has managed to pave. But there’s minimal damage, no injuries, and the couple's spirit is high. Marsha told me, “I was very leery about this. I wanted to go to Europe, but I asked if we couldn’t do it in a car. Now, I wouldn’t do it any other way.”

Neither would Sonny Alafriz, a Phoenix anesthesiologist, whose reasons for being on this trip were simple: “Hey, I enjoy coming to Europe, and I like to ride motorcycles. I love the food, and I like the quaint little towns. It was take this trip or put in new carpet and linoleum. We chose the trip." That choice cost him the standard AlpenTour-West rates: $3.795 for himself and $3,1 95 for Brenda Szynaka. his passenger. To those rates must be added the cost of airfare to Chicago, the trip's starting point, plus fuel, refundable (with luck) insurance deposit and incidentalexpenses, for a minimum of $8000 per couple. But even early on, Alafriz is certain the trip beats the tar out of installing new flooring.

The next day, we're heading towards Montreaux, 130 miles and four mountain passes away in the French-speaking section of Switzerland. Laura and I are on our own, feeling just maverick enough to not enjoy accommodating ourselves to anyone else's pace through this cold, foggy morning. We head through rolling farmland to the Jaunpass, hit medieval Gruyeres fora late lunch stop, and coast into Montreaux just before sunset.

We're having a bit of trouble remaining on course, in spite of highly detailed maps and routes custom-marked just for us. We're never really lost. But sometimes we’re almighty confused. Is it just us? Apparently not.

Jane Parnés, here from Southern California for a little fast sport-touring with Marc, her husband, commented, “We’re lost at least once a day.” But being lost failed to dampen her enthusiasm. “Even at the speeds we're going,” she said, “You get a picture of what life here is like. The trip is fantastic.”

We've a day's rest in Montreaux. and, still recovering from the 22 hours of travel that brought us to Switzerland.

we re grateful for that. By now. our group is jelling into a family unit. And while some of the bunch go riding, most of us tour castles, schmooze the locals and walk the city.

I ve been promising Laura a look at big-time speed, assuring her that every wife needs this. She’s not so sure, hoping, I think, that the opportunity will fail to present itself. Ah, but the first 30 miles of the next day’s route, clockwise around Mont Blanc, into France and finishing up in a ski resort named St. Gervais, are on the autobahm There s a 75-mph limit here, but there are no cops and no traffic. So we go for it, pegging the big Katana’s 260kilometcr-per-hour speedo, and holding it there for a spell. That works out to 162 miles an hour, and even allowing for speedometer error, we’re cooking along at about 150& Laura gamely tucks in behind me and hangs on, but later, in a comic pantomime, she rolls her eyes and heaves a sigh of relief when I promise not to repeat this. It’s an easy promise to make, because flat-out, straight-line running is, for me, at least, an uncomfortable, oddball mix of apprehension and ennui. And fuel costs from $3.50 to $4.25 per gallon; the faster you run, the more you spend. Still, it’s nice to air the Katana out every once in a while, especially this far away from U.S. authorities and my home-town insurance agent. For the rest of the trip, we confine ourselves to speeds no greater than about 120 miles an hour.

Supper this night is a very tense affair; four bikes have gone down. Two are written off, two riders are injured.

The strain is evident on Desmond’s face, and his nightly exhortations about safety are especially fervent. We begin the next day’s ride with increased caution.

We’re headed through the Provence region of Southern France towards Digne les Bains. It’s a terrific ride through lovely, sweeping countryside filled with fall odors and colors. Laura's an eager traveler, with a probing, intelligent, curiosity, but she has her doubts about the wonders of Prance. These doubts are reinforced when we stop for a potty break and discover that the mens and womens facilities consist of just one not-so-private room, where a pair of porcelain footpads are set astride a concrete hole in the floor.

Tex Weston, a Pennsylvanian who is one of the bad-boy Benz gang, lightens the mood when he volunteers that he’s conducting a survey. So far, he says, Europe has presented him with 26 different ways to flush a commode. When there is a commode.

Af ter taking a day to explore Digne and the surrounding countryside, we head for Monte Carlo, the trip’s midpoint. Though we take every wrong turn possible, we ride too quickly, and pay for this sin by arriving before the luggage van does. So, we stroll Monte Carlo’s topless beaches, wearing our riding clothes. People look at us funny; what they wear on these beaches is mostly a tan. I try not to stare. Especially after Laura gives me The Look when she catches me doing just that.

Voyeurism aside, there's only one thing I want to do here, and that’s tramp the Grand Prix course. While doing so, we run into Ringo Starr, just about to step into the Hotel de Paris. I tell him the last time I saw him was at Dodger Stadium, must have been 1966. He doesn't remember me. Can't, in fact, get away from me fast enough. Funny guy.

Desmond knows we bee-lined here, passing on some of his recommended cultural stops, and that seems to bug him. A day later, as we ready ourselves for the trip back towards Switzerland, he booms, “Coming with me on the cultural ride today?” We’re coming, and doing so proves to be to our great advantage. We're heading into Italy, and Desmond knows the roads. He’s been doing this for 10 years, so he also knows the villages, and in some cases, the people in them. He calls a lunch halt in Ceriana, a 2500year-old town where he shows us Roman walls and the interior of a 1 500-year-old church. He lifts a board on the church’s floor, and we peer into the hole it covers. It contains the bones of the region's saints.

“My frustration,” he says, the bones of the saints safely hidden again, “is that only a few of our people will actually stop and walk this magical place.”

Öur stop this evening is in Santa Vittoria d'Alba, where another kind of magic is happening: The white truffle season is in full swing. You only live once, right? For 1 5,000 lira (about 1 1 bucks) each, we allow our maître d' to grate a bit of truffle—a fleshy, underground fungus— onto our pasta. This imparts a musty flavor not unlike the smell of overripe cheese. I vow not to do this again.

More culture the next day. We head for a farming community called Poll en zo, which contains an abandoned palace. Across from it, and separated from it bv a cobblestone plaza, is an abandoned cathedral. Both structures from the 16th century, are solid and beautiful, untouched by time. This is the Europe I thought had been lost, bombed away and torn down. But it remains, it’s real, and it s all linked by majestic roads.

One oí these is a section of Roman road, cut with iron tools from solid granite, which we find as we enter Aosta, this night’s stop. Our women are up in arms: There’s shopping to be done here, and a beautifully preserved, vibrant old city to explore, but little time in the tour schedule to do either.

The next day, we explore the road to an abandoned castle called ( hateau Graines. As the road narrows, we abandon our full-tilt lean-angles to idle through a herd of dairy cows, who pay no attention at all to us. After a stop to chat with the villagers in Graines, who, unaccountably seem delighted to see us, we head for Stresa, a jewel-like resort city on the shore of Lake Maggiore. This stop notable because this is where Tex Weston runs up the trip s championship bar tab—$400 in one night. A manly effort, we assure him. He seems barely able to hear us.

4 he next morning, we head for Switzerland and our ayover for the next two nights, Interlaken, the designated AlpenTour shopping venue. An odd day, this, divided into two parts. 4 he first takes us over very fast roads, one of which, on its way to snowy Simplon Pass, takes us through a pitch-black tunnel with an off-camber left-hander in it. Scares me to death. The day’s second phase consists of stop to check out the Matterhorn-the Swiss have done good with this, they’ve copied the one at Disneyland exactly—and then an unlikely train ride. For this, we stop at village called Goppenstein, load our bikes aboard the train’s special motorcycle car, and ride through a 9-mileIong tunnel hewn through the Alps. This diversion is necessary because Europe’s first winter storm has closed the passes between us and Interlaken. The automobile transport train is the only way to get there.

Interlaken’s a good stopover spot, because there’s lots to do, including up-close-and-personal looks at alpine peaks via tram and helicopter, hikes through beautiful Swiss villages. a look at the waterfall from which Sherlock Holmes met his end at the hands of the infamous Dr. Moriarty, and, in what must be the oddest clash of cultures, beer drinking at a genuine Swiss country-and-western bar.

We leave it all too soon. Two weeks have passed and we haven t even started to get enough of riding here. But, suddenly, the last day of our tour arrives. I'm feelin« betrayed by time and circumstance. I he day begins with hoots from our group, as the Kawasaki Concours of the safety-conscious Desmond falls from its stand and dents its fuel tank against a steel pole. “That'll cost me 500 bucks,” he laments.

Rain, a European constant, has been absent so far but on the last hour of the ride between Interlaken and Zurich, finally it checks in. We wick it to our hotel without stopping to put on rain gear, and once there, our riding clothes soggy and uncomfortable, the reality of things hits us. We maybe have bitched about a few things on this trip, but we re not ready for it to be over; we don't want to go home We want to go right on following Desmond for another two weeks, and maybe for a couple of weeks after that.

It s possible to argue that taking a tour, even one which offers this one's custom-drawn routes, robs you of the delicious risks that make travel so rewarding: solo navigation. exploration, and the interaction with the natives that is so necessary in the search for food and lodging. But a tour's advantages remain considerable. These include not hav ing to haul all your luggage on your bike, the assurance that any problem with your bike will be handled, the readv availability of detailed knowledge about the best routes, inside information about historic and cultural points along the way, and the knowledge that you don’t have to hassle w ith finding a room at night. These points weigh, I think, against the freedom of soloing, and I suspect that for most of us, a tour’s the way to go.

What’s more important than how you go, though, is just going, and riding those wonderful roads.

I or a motorcyclist to never ride in Europe, that’s like a surf er never hearing of Hawaii, Desmond said over lunch one day.

I think he's right. ¡g

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

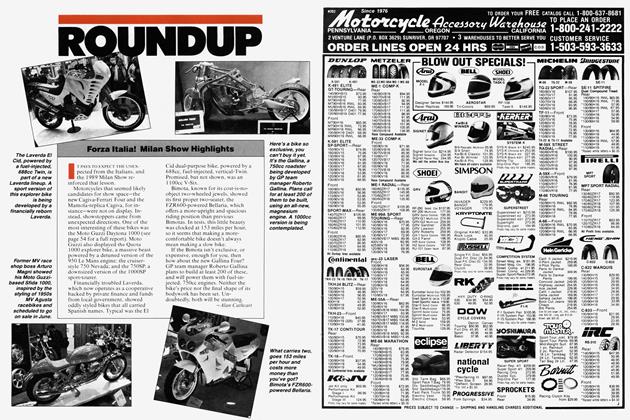

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990