UP FRONT

Miscellany

WE’RE LOOKING FOR A FEW GOOD readers. One hundred, to be exact.

That’s the number of people who we hope will take part in an experiment we’re about to try. It’s called the Cycle World 100 Readers Group, and it’ll be our very own focus group.

For those of you who don’t know, focus groups are made up of a cross-section of people and are used by many companies, including motorcycle manufacturers, to sample public reaction to new designs.

We’d like to use the Cycle World 100 as an opinion-gathering device, a network of 100 far-flung voices with something to say about the sport of motorcycling. We’ll be asking for— and publishing—the group’s views about various issues, including, yes, bike design, but also things like helmet use, insurance costs and impending anti-motorcycle legislation. We’ll also tackle less-weighty subjects. One of the ideas is to have Readers’ Choice awards to go along with our annual Ten Best Bikes balloting. And if we can work out the logistics, we may even invite select members to help us with comparison tests, adding an Everyman’s perspective to the proceedings. We look upon the group as a chance to add 100 amateur correspondents to the CW staff.

If you’d like to be considered for the group, please fill out and send in the bound-in postcard you’ll find between pages 10 and 1 1 of this issue. We’re looking for enthusiasts from all segments of motorcycling, people who’ll take the time and make the effort to respond to our questions. We’re going to pick at least one group member from each of the 50 states, and those chosen will receive an exclusive Cycle World 100 Readers Group T-shirt. The deadline for entries is August 1. We hope to hear from you.

THERE’S A NEW OLD MOTORCYCLE

draining the Edwards household’s checking account: a 1946 Velocette GTR And if you don’t know what the heck that is, don’t feel bad. I didn’t, either, when I spied the ad for it in a classic-bike publication.

A little research cleared some of the fog. At the risk of boring all 500 or so U.S. Velocette aficionados, the apparently French company was actually British, based in the wonderfully Anglo-sounding town of Hall Green. Until 1971, that is, when Veloce Ltd., best known for its finely crafted 350 and 500cc Singles, went the way of all British bike builders and closed its doors for good. The GTP, introduced as a 1930 model, was one of the firm’s few twostrokes, painted like most of Veloce’s wares in gloss black with a gold-pinstriped fuel tank. The bike’s 250 cubic centimeters of unbridled power translated into a breakneck top speed of 57 miles per hour, though it would return almost 90 miles for each gallon of petrol burned.

When I went to see the bike— rather optimistically advertised as “98 percent complete’’ —I was greeted by several tabletops’ worth of scattered parts, more a large, threedimensional jigsaw puzzle than an actual motorcycle. I’m a sucker for a bike that needs a good home, though, and after some haggling over the price, the stack of GTP parts was mine. As you read this, frame tubes are being straightened, engine cases are being beadblasted, wheels are being rebuilt, fenders and fuel tank are being repainted, parts are being chased, and I'm signing a lot of checks for the restoration of a bike that only cost about $200 when new.

It helps to remind myself that old bikes are solid investments, that no matter how much you pay for one, eventually it will be worth more. I just hope that’s true of little black Velocettes.

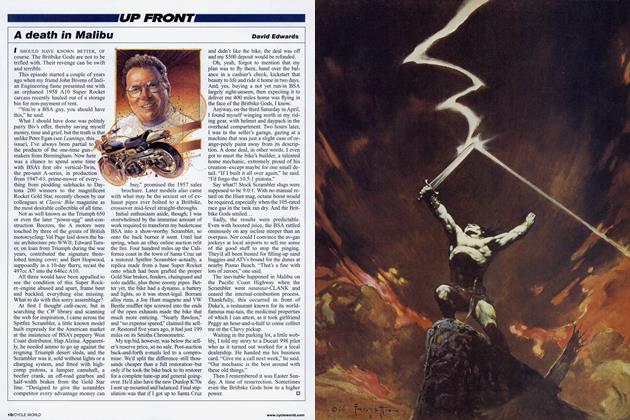

I'VE GOT TO LIKE A GUY WHOSE FIRST

motorcycle was “a mean old 1946 Indian Chief. I remember how proud of it I was—I right away went over to see this girl I was dating to show it to her. When she saw it, she said, ‘You don’t expect me to ride around with you on thatT Well, I sure enough did. The girl went, but the bike stayed.”

The year was 1950 and the Indian owner was a struggling actor named Steve McQueen, then 21.

I ran smack dab into McQueen last weekend. I was sorting out my magazine collection and came across a 1971 issue of Sports Illustrated, with a nicely done story about McQueen’s love of dirtbikes. The cover (one of only two in STs 35-year history to portray motorcycles) showed a barechested McQueen gunning his Husky motocrosser across the harsh desert.

By sheer coincidence, I bumped into him again that same weekend when a local TV station ran The Great Escape, the 1963 movie in which McQueen takes part in a mass breakout from a WWII German prison camp and tries to flee to Switzerland on a stolen motorcycle. His mad dash through the Alpine countryside, highlighted by slides, jumps and wheelies, was as good an advertisement for the joy of motorcycling as was the acclaimed 1971 semidocumentary On Any Sunday (which McQueen helped finance).

McQueen, who died 10 years ago at age 50 of a heart attack following cancer surgery, drove fast sports cars, flew biplanes and collected old guns, but motorcycles remained the man’s “prime passion,” as William F. Nolan put it in his excellent biography, McQueen. Nolan quotes his friend McQueen as saying, “I’d rather run a fast bike over clean desert than do anything else in the world . . . I’m out there alone, on a fast bike—just me and the desert and a slice of clean blue sky, with the wind around me and the cactus and the sound of that engine at high revs . . . It’s pure. It’s freedom—maybe the only real freedom there is.”

One of McQueen’s co-stars, Faye Dunaway, once said of him, “He’s a risk-taker. That cutting edge of his comes across on film.”

And, it could be added, in life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

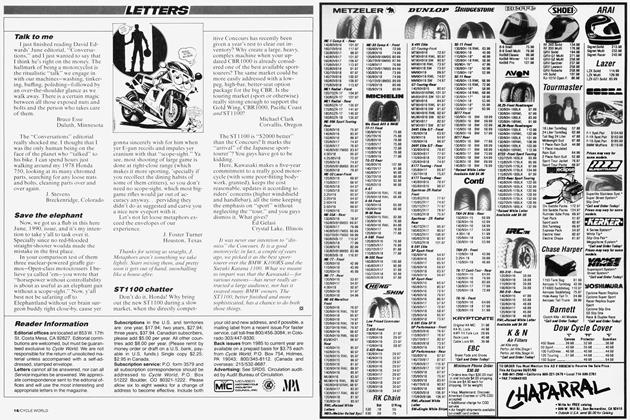

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart