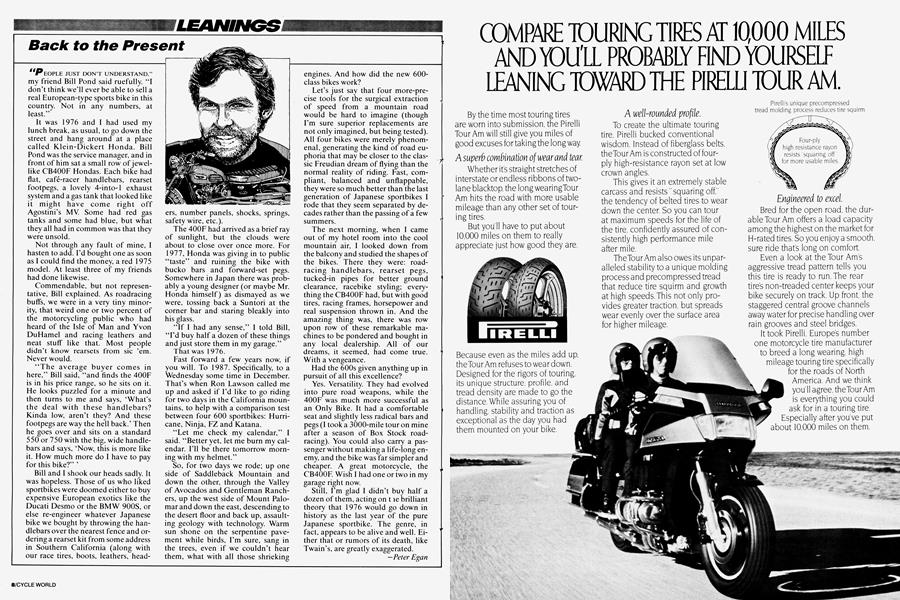

Back to the Present

LEANING

PEOPLE JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND,”

my friend Bill Pond said ruefully. “I don’t think we’ll ever be able to sell a real European-type sports bike in this country. Not in any numbers, at least.”

It was 1976 and I had used my lunch break, as usual, to go down the street and hang around at a place called Klein-Dickert Honda. Bill Pond was the service manager, and in front of him sat a small row of jewellike CB400F Hondas. Each bike had flat, café-racer handlebars, rearset footpegs, a lovely 4-into-l exhaust system and a gas tank that looked like it might have come right off Agostini’s MV. Some had red gas tanks and some had blue, but what they all had in common was that they were unsold.

Not through any fault of mine, I hasten to add. I’d bought one as soon as I could find the money, a red 1975 model. At least three of my friends had done likewise.

Commendable, but not representative, Bill explained. As roadracing buffs, we were in a very tiny minority, that weird one or two percent of the motorcycling public who had heard of the Isle of Man and Yvon DuHamel and racing leathers and neat stuff like that. Most people didn’t know rearsets from sic ’em. Never would.

“The average buyer comes in here,” Bill said, “and finds the 400F is in his price range, so he sits on it. He looks puzzled for a minute and then turns to me and says, ‘What’s the deal with these handlebars? Kinda low, aren’t they? And these footpegs are way the hell back.’ Then he goes over and sits on a standard 550 or 750 with the big, wide handlebars and says, ‘Now, this is more like it. How much more do I have to pay for this bike?” ’

Bill and I shook our heads sadly. It was hopeless. Those of us who liked sportbikes were doomed either to buy expensive European exotics like the Ducati Desmo or the BMW 900S, or else re-engineer whatever Japanese bike we bought by throwing the handlebars over the nearest fence and ordering a rearset kit from some address in Southern California (along with our race tires, boots, leathers, headers, number panels, shocks, springs, safety wire, etc.).

The 400F had arrived as a brief ray of sunlight, but the clouds were about to close over once more. For 1977, Honda was giving in to public “taste” and ruining the bike with bucko bars and forward-set pegs. Somewhere in Japan there was probably a young designer (or maybe Mr. Honda himself) as dismayed as we were, tossing back a Suntori at the corner bar and staring bleakly into his glass.

“If I had any sense,” I told Bill, “I’d buy half a dozen of these things and just store them in my garage.”

That was 1976.

Fast forward a few years now, if you will. To 1987. Specifically, to a Wednesday some time in December. That’s when Ron Fawson called me up and asked if I’d like to go riding for two days in the California mountains, to help with a comparison test between four 600 sportbikes: Hurricane, Ninja, FZ and Katana.

“Fet me check my calendar,” I said. “Better yet, let me burn my calendar. I’ll be there tomorrow morning with my helmet.”

So, for two days we rode; up one side of Saddleback Mountain and down the other, through the Valley of Avocados and Gentleman Ranchers, up the west side of Mount Palomar and down the east, descending to the desert floor and back up, assaulting geology with technology. Warm sun shone on the serpentine pavement while birds, I’m sure, sang in the trees, even if we couldn’t hear them, what with all those shrieking engines. And how did the new 600class bikes work?

Fet’s just say that four more-precise tools for the surgical extraction of speed from a mountain road would be hard to imagine (though I’m sure superior replacements are not only imagined, but being tested).

All four bikes were merely phenomenal, generating the kind of road euphoria that may be closer to the dassic Freudian dream of flying than the normal reality of riding. Fast, compliant, balanced and unflappable, they were so much better than the last generation of Japanese sportbikes I rode that they seem separated by decades rather than the passing of a few summers.

The next morning, when I came out of my hotel room into the cool mountain air, I looked down from the balcony and studied the shapes of the bikes. There they were: roadracing handlebars, rearset pegs, tucked-in pipes for better ground clearance, racebike styling; everything the CB400F had, but with good tires, racing frames, horsepower and real suspension thrown in. And the amazing thing was, there was row upon row of these remarkable machines to be pondered and bought in any local dealership. All of our dreams, it seemed, had come true. With a vengeance.

Had the 600s given anything up in pursuit of all this excellence?

Yes. Versatility. They had evolved into pure road weapons, while the 400F was much more successful as an Only Bike. It had a comfortable seat and slightly less radical bars and pegs (I took a 3000-mile tour on mine after a season of Box Stock roadracing). You could also carry a passenger without making a life-long enemy, and the bike was far simpler and cheaper. A great motorcycle, the CB400F. Wish I had one or two in my garage right now.

Still, I’m glad I didn’t buy half a dozen of them, acting on t íe brilliant theory that 1976 would go down in history as the last year of the pure Japanese sportbike. The genre, in fact, appears to be alive and well. Either that or rumors of its death, like Twain’s, are greatly exaggerated.

Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue