Raised Standards

AT LARGE

AS THE BRITISH AIRWAYS BOEING climbed out from Munich airport headed for London, I looked down on the tidy German countryside and wondered about the trip just past. Sometimes a motorcycle ride is just a ride, not a transcendental experience, and sometimes the bike is just a machine.

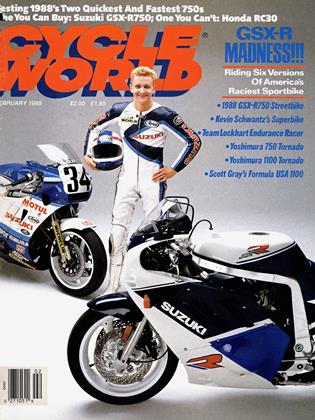

Not this time. This time, the ride was the Over the Hill Gang’s Alpine Adventure II; and while the five days of riding in the Dolomites wasn’t exactly transcendental, it surely wasn’t just a ride, either. Obviously, it would take some time for the real meaning of what the 16 of us had done together to clarify. You don’t mix up middle-aged motorcyclists from America, Holland, Sweden and Spain, put them aboard bikes spanning the spectrum from Honda CX500 to full-blown Harris-Kawasaki Magnum Three and not expect some wild times. And wild times there had been. But what made the trip memorable for me was the bike I rode, and what I realized it meant about the state of the art.

The bike was a BMW K75C. And it took me until the fourth day of riding to understand that what it meant was wholly new standards for “standard” motorcycles.

You remember “standards.” They were the bikes that filled our showrooms and garages until only yesterday; bikes like the Triumph Bonneville, built and sold to us by guys who understood that the final touches that made them ours would be put on not by a dealer accessory package or a manufacturing robot, but by us. After the purchase. We’d buy the thing and maybe have half-a-dozen different guises for it; when we felt roadracy we’d fit Clubman bars, sticky tires, rearset footpegs, a different exhaust and on and on until our budgets ran out. Then, after we’d ground off some metal and scared ourselves silly, maybe, we’d bolt on taller bars, buy a fairing and go touring, taking off the fairing when it got simply too hot, around August.

Just about everybody remembers these kinds of bikes. Their disappearance within the last five years has been cause for much public discussion in bike shops and magazines like this one. Older enthusiast and newer both seemed to recognize the unique attraction of a universal motorcycle; but, beseiged by today’s specialized hardware that performs in each category better by far than any of the old standards, what were any of us to do, save grumble and buy an old bike to supplement the highly focused wonderbikes? There seemed, in the new-bike array, no satisfactory alternative.

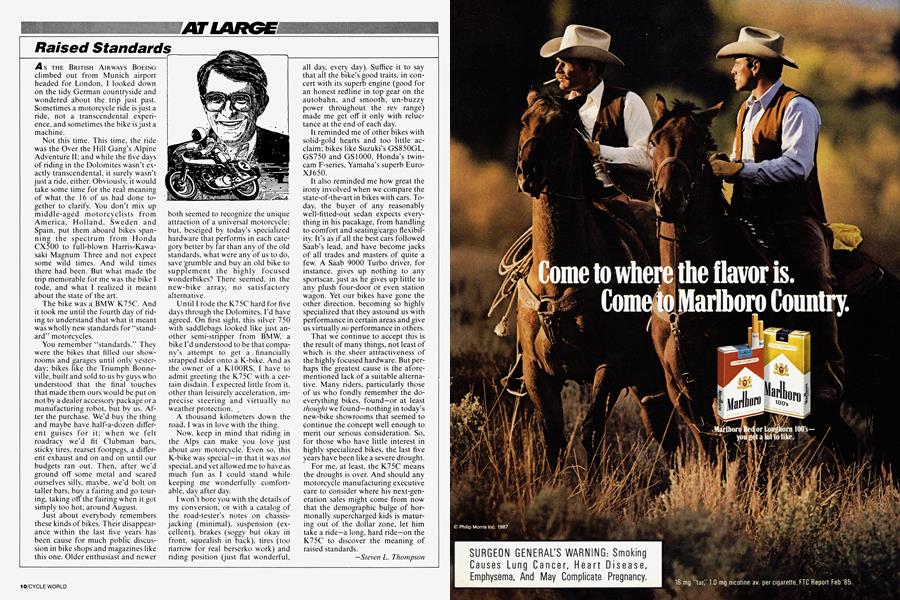

Until I rode the K75C hard for five days through the Dolomites, I’d have agreed. On first sight, this silver 750 with saddlebags looked like just another semi-stripper from BMW, a bike I’d understood to be that company’s attempt to get a, financially strapped rider onto a K-bike. And as the owner of a K100RS, I have to admit greeting the K75C with a certain disdain. I expected little from it, other than leisurely acceleration, imprecise steering and virtually no weather protection.

A thousand kilometers down the road, I was in love with the thing.

Now, keep in mind that riding in the Alps can make you love just about any motorcycle. Even so, this K-bike was special—in that it was not special, and yet allowed me to have as much fun as I could stand while keeping me wonderfully comfortable, day after day.

I won’t bore you with the details of my conversion, or with a catalog of the road-tester’s notes on chassisjacking (minimal), suspension (excellent), brakes (soggy but okay in front, squealish in back), tires (too narrow for real berserko work) and riding position (just flat wonderful,

all day, every day). Suffice it to say that all the bike’s good traits, in concert with its superb engine (good for an honest redline in top gear on the autobahn, and smooth, un-buzzy power throughout the rev range) made me get off it only with reluctance at the end of each day.

It reminded me of other bikes with solid-gold hearts and too little acclaim; bikes like Suzuki’s GS850GL, GS750 and GS1000, Honda’s twincam F-series, Yamaha’s superb EuroXJ650.

It also reminded me how great the irony involved when we compare the state-of-the-art in bikes with cars. Today, the buyer of any reasonably well-fitted-out sedan expects everything in his pacakage, from handling to comfort and seating/cargo flexibility. It’s as if all the best cars followed Saab’s lead, and have become jacks of all trades and masters of quite a few. A Saab 9000 Turbo driver, for instance, gives up nothing to any sportscar, just as he gives up little to any plush four-door or even station wagon. Yet our bikes have gone the other direction, becoming so highly specialized that they astound us with performance in certain areas and give us virtually no performance in others.

That we continue to accept this is the result of many things, not least of which is the sheer attractiveness of the highly focused hardware. But perhaps the greatest cause is the aforementioned lack of a suitable alternative. Many riders, particularly those of us who fondly remember the doeverything bikes, found—or at least thought we found—nothing in today’s new-bike showrooms that seemed to continue the concept well enough to merit our serious consideration. So, for those who have little interest in highly specialized bikes, the last five years have been like a severe drought.

For me, at least, the K75C means the drought is over. And should any motorcycle manufacturing executive care to consider where his next-generation sales might come from now that the demographic bulge of hormonally supercharged kids is maturing out of the dollar zone, let him take a ride-a long, hard ride-on the K75C to discover the meaning of raised standards.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Rounup

RounupDestinations

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Van Zuyle