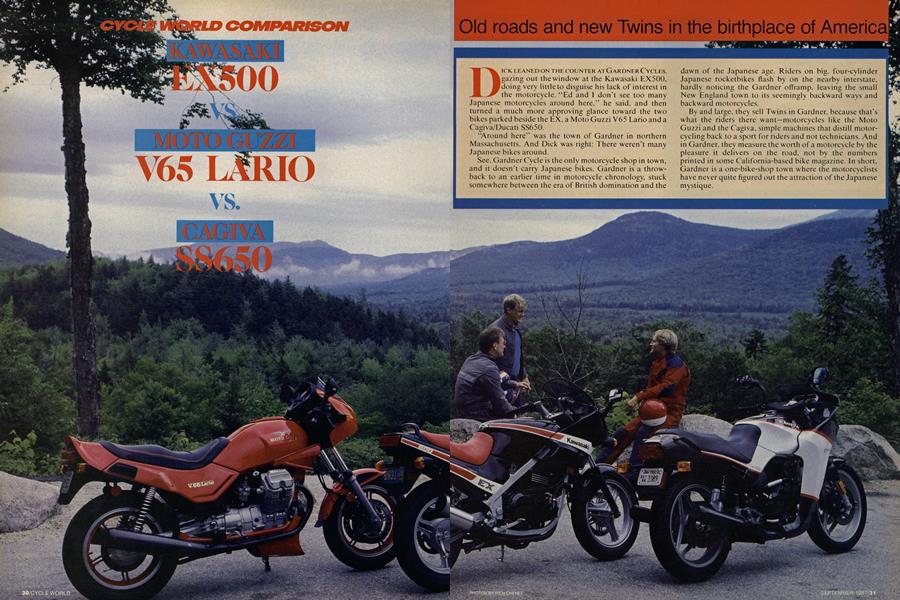

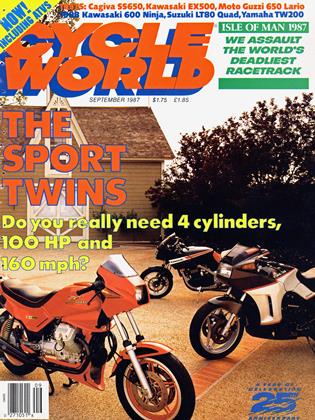

KAWASAKI EX500 VS. MOTO GUZZI V65 LARIO VS. CAGIVA SS650

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

Old roads and new Twins in the birthplace of America

DICK LEANED ON TUE COUNTER AT GARDNER CYCLES. gazing out the window at the Kawasaki EX500, doing very little to disguise his lack of interest in the motorcycle. "Ed and I don't see too many Japanese motorcycles around here,” he said, and then turned a much more approving glance toward the two bikes parked beside the EX, a Moto Guzzi V65 Lario and a Cagiva/Ducati SS650.

“Around here” was the town of Gardner in northern Massachusetts. And Dick was right: There weren’t many Japanese bikes around.

See, Gardner Cycle is the only motorcycle shop in town, and it doesn't carry Japanese bikes. Gardner is a throwback to an earlier time in motorcycle chronology, stuck somewhere between the era of British domination and the dawn of the Japanese age. Riders on big, four-cylinder Japanese rocketbikes flash by on the nearby interstate, hardly noticing the Gardner offramp, leaving the small New England town to its seemingly backward ways and backward motorcycles.

By and large, they sell Twins in Gardner, because that’s what the riders there want—motorcycles like the Moto Guzzi and the Cagiva, simple machines that distill motorcycling back to a sport for riders and not technicians. And in Gardner, they measure the worth of a motorcycle by the pleasure it delivers on the road, not by the numbers printed in some California-based bike magazine. In short, Gardner is a one-bike-shop town where the motorcyclists have never quite figured out the attraction of the Japanese mystique.

But the Kawasaki is at least one Japanese bike that might be able to survive in Gardner. The EX500 fits the small-town mold for how a motorcycle should be. It appears to be Japanese only by some accident of geography, having more in common with bikes like the Guzzi and the Cagiva than it does with the multi-cylinder machines that more typically come from its country.

We made these observations while riding all three of these Twins on the backroads and highways of New England. That ride helped us understand what these verysimilar-but-entirely-different bikes are all about. It also helped us learn quite a lot about the Northeast.

Now, just about the entire staff of CYCLE WORLD is made up of non-native Californians, a few of who have even lived in New England. And each staffer has, at one time or another, owned European metal. But too many years in La-La Land have dulled the memory. We don’t keep change handy for eastern-style toll roads anymore; we tend to forget what annual freezing and thawing does to once-smooth asphalt.

At least the machinery is familiar enough. All three of these bikes are, of course. Twins, but the similarities don’t stop there. All three are targeted somewhere between allout sport hardware and more civil, touring-style bikes. If you had to give them a name, middleweight sport-tourers wouldn't be a bad one.

When it comes down to specifics, though, all three machines take different approaches to arriving at the same destination. The Guzzi is an overhead-valve, 90-degree V with a longitudinal crankshaft and shaft final drive. The pushrod engine is hardly on the leading technological edge, although it does have four valves per cylinder. The advantage of the Guzzi's layout is primarily in simplicity of maintenance—a decent mechanic can have a piston out of the engine and in his hand in about 20 minutes.

The Cagiva is the same tune played to a slightly different beat. It also is a 90-degree V-Twin, but with a transverse crank and chain drive. The Ducati motor is a singleoverhead-cam, two-valve-per-cylinder model, and it's correspondingly harder to service than the Guzzi. The desmodromic valve system does away with valve springs, but while adjusting the valves isn't a mechanic’s nightmare, it’s at least an unpleasant dream.

Kawasaki's approach is a transverse vertical Twin with chain final drive. The EX's only high-tech twists are its four valves per cylinder and liquid-cooling, if you can still call such features high-tech. Rather, the Kawasaki is just a good, solid design, built around an engine that was originally used in the 454 LTD.

Despite their engine-configuration differences, all three bikes share a singularity of purpose. They weren’t built to set new quarter-mile records, and they weren't made to emulate Eddie Lawson’s latest GP bike. The Guzzi Lario, the Cagiva SS and the Kawasaki EX were made for the road. They were made for riding and for the enjoyment of the ride.

And it’s on a long ride where you learn all about what makes this a very special breed of motorcycle. These are bikes you can't ride for just a few miles and hope to understand. You have to experience them for days before you come to terms with their way of doing things. It isn’t so much what these motorcycles do that’s important, but the way they make you feel.

The Guzzi, for example, lulls its rider down the road, playing a bass melody with the gentle loping of its motor. On the highway, the Lario loves to be shifted into high gear and have its thumbscrew-style cruise control locked just a crack above idle. The engine pulses smoothly, and vibration only raises its annoying head above 5000 rpm—and even then, it isn't the high-frequency buzzing that afflicts many four-cylinder motorcycles, but more of a soft shake.

The Ducati motor does its shaking at the other end of the rpm scale. In top gear, it snorts and rattles until you bring it up above 65 mph, where it then begins to smooth out and act more civilized. Both of these Italian bikes are geared tall and appreciate wide-open spaces where they can stretch their legs and run.

No matter what the speed, the Kawasaki’s vibration level doesn’t change much: It’s always fairly smooth. The EX does have more of a buzz than a shake, but it’s still no bother at all compared to what you feel on most modern sportbikes. The engine revs much more quickly than do those in the other Twins, and has the sound and feel of a small, responsive motor. But that’s not surprising, considering that the Kawasaki has the smallest engine of the trio.

The EX500 also has the smallest chassis of the bunch. Compared to either of the V-Twins, the Kawasaki feels tiny, almost toy-like. Nevertheless, its seating position is more spread-out than those on any of the Japanese 600s; by FZ or Ninja standards, the EX has low footpegs and fairly high bars. The seat is rather low, however, so the rider’s legs still are a bit confined. By comparison, the Cagiva is much more spread-out, giving the rider more or less the same amount of room as found on the “standard" motorcycles of the Seventies.

On the Lario, the seat-to-footpeg relationship is almost the same as on the Cagiva, but Moto Guzzi took the GPracer approach to upper-body positioning. The handlebars are clip-ons that cant downward and rearward, putting the rider in a full tuck. Thus, the Guzzi has the least-comfortable rider positioning of the three for highway touring, only because so much of the rider’s weight is on his hands.

And the amount of rider weight that’s on the Guzzi's saddle isn’t all that well cared-for, either. The Lario’s seat is typically Italian—that is, hard, and shaped nothing at all like a human seat. It’s wide, flat and has fairly sharp edges. It's not all that bothersome on a short ride, but by the time you get very far outside of even a small town the size of Gardner, the numbness in the nether regions starts getting more and more aggravating.

About the only good thing you can say about the Guzzi’s seat is that it’s better than the Cagiva’s. While the contour of the SS’s seat looks like it might not put anyone in the traction, the foam is absurdly dense. So once again, by the time you’re ready to stop for dinner, you’re also ready to eat standing up.

Voted most likely not to numb is the Kawasaki seat, with its medium-soft foam and well-rounded shape. It's not the Best Seat Ever In The History Of Things To Sit On, but it seems that way in contrast to those on the Cagiva and Guzzi.

Besides, New England roads aren’t the type that keep you planted in the same part of the seat for hours on end. Variety is what this part of the country is all about. There’s variety in roads, from superhighways to backroads that make the average motocross track seem smooth by comparison. And there’s variety in weather; it seems that by the time you get your rain gear on, it’s usually sunny and 90 degrees, and by the time you get your rain gear oft, you can count on frigid rain.

We also discovered that the backroads of New England have an inordinately high policeman-to-motorcyclist ratio. No wonder riders in these parts scratch their heads and ask why anyone would want a 160-mph motorcycle. By the time you get any bike up to that kind of speed, you’ll have gone through seven small towns and passed seven small-town police stations. There are sheriffs in Maine who have waited their whole lives for out-of-state motojournalists to try any of that road-test nonsense in their county.

Of course, even if all civil sense were suspended, scoring a 160-in-a-35 rap with these bikes isn’t a realistic worry— although all three still are plenty capable of earning their riders a trip to the local traffic court. The Kawasaki is the most powerful of the lot, even if it’s not the torquiest or the peakiest. Torque awards go to the Cagiva, which pulls from way down low with the satisfying, irregular beat that V-Twins do so well. After the initial power burst, however, the power of the Ducati engine tapers off. At high revs (meaning over 6000 rpm), the motor settles down, and more throttle is rewarded with more engine noise, but not necessarily more power.

Turn the Cagiva powerband upside-down and you’ve got the Guzzi powerband. Off the bottom, the Lario just plods lazily along, its heavy-flywheel feel doing little to excite. But once the engine climbs up over 6000, it starts to have some punch. In fact, the Guzzi will easily overrev its 7700-rpm redline unless the rider keeps a careful eye on the tach and shifts right on cue.

Still, even when the Guzzi’s engine is kept near the top of its rather narrow powerband, the Lario won’t run with the Kawasaki. Neither, for that matter, will the Cagiva. The EX has a revvy motor that is light on flywheel and heavy on acceleration, so it just runs away from the others when the need arises.

Another area where the EX excels is in suspension. We came to that conclusion in New Hampshire, which is—by our observation, at least—a suspension tester’s worst fears and dream-come-true all rolled into one. That’s another way of saying that the roads there are rough. It’s as if some malevolent road-wrecker paced off every 20 feet of asphalt in the state and planted a land mine. So, as you can guess (and as riders in that area undoubtedly already know), a brisk pace on a motorcycle there means you spend a lot of time being airborne.

Obviously, such conditions do not favor the two European bikes, which are stiffly suspended. In the case of the Cagiva, road roughness also often results in an unsettling head shake. Along with being too stiff, the Marzocchi fork seems unable to cope with sudden loads; it doesn’t even try to react to those volcano-class New Hampshire bumps. The rear end is better, although still on the stiff side, a condition made less tolerable by the SS650’s hard seat.

Both ends of the Guzzi also are just as stiff. The Lario never does anything heart-stopping as a result, but the miles can begin to take their toll during a long ride on rough roads. But in all fairness, even the Kawasaki suspension is unable to deal with the roughest roads that New England has to offer. It’s the only single-shocker of the bunch, and it’s the smoothest-riding bike of the three, but streetbike suspension technology hasn’t evolved enough to make those kinds of roads seem even remotely smooth.

Motorcycle technology has, however, progressed far enough that you shouldn’t have to put up with things like the Cagiva’s controls. Its grips are hard and shaped poorly, the levers are flat and uncomfortable, and the master cylinder for the hydraulic clutch doesn’t allow full clutch disengagement. The Guzzi and the Kawasaki score much better in this department, both having good levers and grips—and clutches that work properly.

Likewise, the Kawasaki and the Guzzi both outperform the Cagiva in just about all braking maneuvers. Actually, the Cagiva’s Brembo brakes get the job done, stopping the bike neither poorly nor superbly, but they demand that you squeeze hard. The Kawasaki unquestionably owns the best front brake of the bunch, despite having only one disc up there instead of two as the other machines do.

In terms of rear brakes, the Lario excels because of its integrated braking system. When you press on the Guzzi’s rear brake pedal, you’re also activating the front brake to a lesser degree. It’s very difficult to lock up the Guzzi’s rear wheel in a panic stop. Using the rear pedal only, the machine just slows, quickly and effectively. Admittedly, most experienced riders already know how to use the front and rear brakes in the proper proportions, but the Guzzi caters to less-experienced riders, as well.

Any rider, experienced or not, will appreciate the Guzzi’s fine finish. Out of these three motorcycles—and perhaps out of any three bikes you care to mention—the Moto Guzzi is the attention-getter. The quality of its bright, arrest-me red paint is as near to perfect as a production bike is likely to get. And in its engine castings, as well as in the fit of all its component parts, the Guzzi is a beautifully finished machine. The Cagiva also has a smooth, well-seen-to appearance that also allows it to be an attention-magnet—so long as it isn’t parked near a crowd-pleaser like the Guzzi.

These two machines prove that fabled Italian craftsmanship is alive and living in more than one area of that country. In contrast, the Kawasaki goes almost unnoticed when in the company of the two Italian bikes. Its paint is quite good, but its overall finish is marred by all-too-visible seams and welds, causing the EX500 to lack the look and feel of an expensive motorcycle.

That’s understandable, of course, considering that the Kawasaki isn 7 an expensive motorcycle, whereas its two Italian companions are. But on a strict, dollars-for-performance basis, the Kawasaki clearly comes out on top. It’s the fastest, most powerful and most comfortable of the three, with the best ride and the best overall brakes—and it retails for just $2899, compared to the Guzzi’s $5045 and the Cagiva’s $4412.

But the folks in Gardner still probably wouldn’t choose it over the Guzzi or the Cagiva. That’s because those sorts of things just aren’t that important to them. They’d point out that even though the Kawasaki is the most powerful in its class right now, it won’t be in a year or so, and if you then want the fastest, you’ll have to throw away a bike every year. All the other factors can be changed, they’d say. And by the time you’ve replaced the shocks and fiddled with this and that, what you wind up with isn’t Cagiva’s motorcycle or Moto Guzzi’s motorcycle, it’s your motorcycle. And that’s worth the extra expense.

Good points, all. Still, though, for us, the Kawasaki is an easy, quantifiable winner. And you know what? We’re willing to bet that Dick and Ed would like the Kawasaki, too. They just wouldn’t admit it.

CAGIVA

SS650 ALAZZURRA

$4412

KAWASAKI

EX500

$2899

MOTO GUZZI

V65 LARIO

$5045

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe High Cost of Higher Performance

September 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeCoached To Success

September 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1987 -

Evaluation

Evaluation"The Care And Feeding of Your Motorcycle"

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupGrass-Roots Saviors?

September 1987 By Charles Everitt -

Roundup

RoundupShort Subjects

September 1987