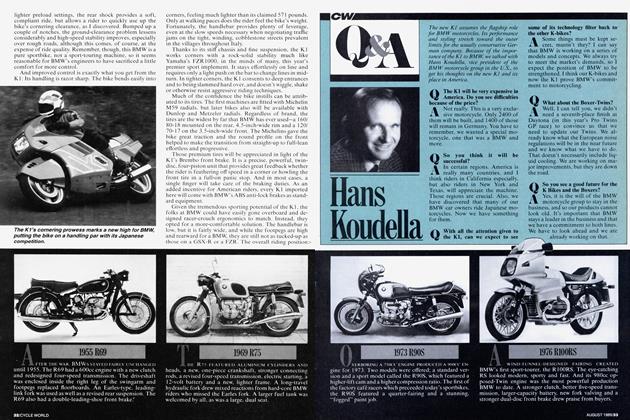

OLDIES BUT GOODIES

Not all of the world’s great music is on records, tapes and compact discs

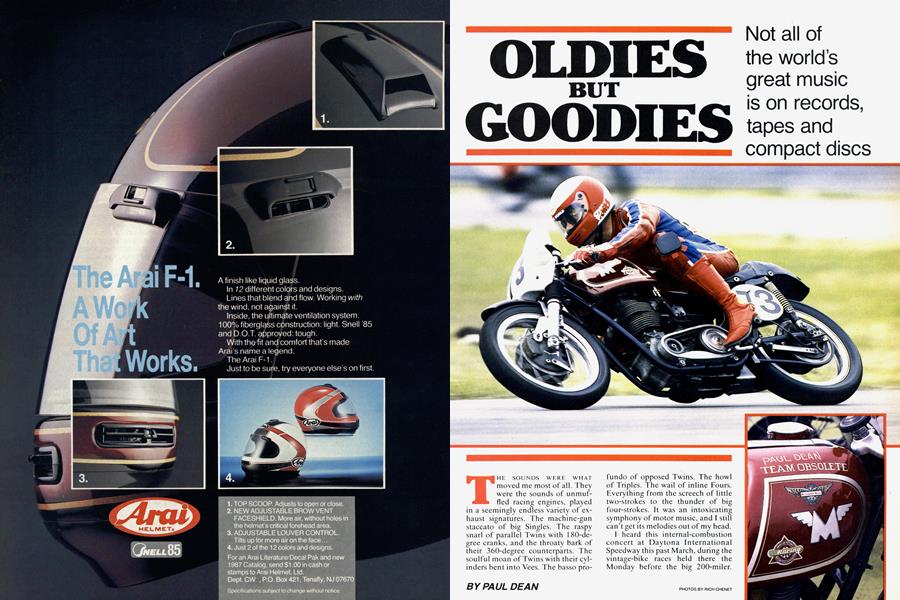

THE SOUNDS WERE WHAT moved me most of all. They were the sounds of unmuffled racing engines, played in a seemingly endless variety ot exhaust signatures. The machine-gun staccato of big Singles. The raspy snarl of parallel Twins with 1 80-de-gree cranks, and the throaty bark of their 360-degree counterparts. The soulful moan of Twins with their cylinders bent into Vees. The basso profundo of opposed Twins. The howl of Triples. The wail of inline Fours. Everything from the screech of little two-strokes to the thunder of big four-strokes. It was an intoxicating symphony of motor music, and I still can’t get its melodies out of my head.

I heard this internal-combustion concert at Daytona International Speedway this past March, during the vintage-bike races held there the Monday before the big 200-miler. I’ve been deeply involved with all kinds of motorcycles for more than 30 years, so I was no newcomer either to vintage roadracing or to all of the many and varied exhaust notes that go along with it. Indeed, I first heard some of those engine sounds back when many of these now-old bikes were brand-new.

PAUL DEAN

But this Daytona encounter was different. Because there, for the first time, I was competing in vintage racing. Actually, it’s now called historicbike racing, because this current breed of old-bike competition incorporates a broader spectrum of older machines than vintage racing. Whatever its name, I was right down in the middle of the action, experiencing all of this marvelous old machinery at close range in the pits and on the track. And that gave me a perspective on this fascinating type of racing— and all of its deliciously different sounds—that I couldn’t have gotten any other way.

My close encounter of the old-bike kind began when Rob lannucci, the impresario of Team Obsolete, asked me if I’d like to ride one of his Matchless G50s in the Daytona historic program. Now, understand that Team Obsolete is to historic-bike racing what Team Yamaha once was to bigtime roadracing: the biggest and most dominant operation in its particular area of the sport. Which means that riding a Team Obsolete bike in a historic race is the equivalent of riding a factory bike in a GP or Superbike race. It was an offer I couldn't—and didn’t—refuse.

Iannucci’s ultimate goal was publicity—not just for his team, but for historic-bike racing in general. This year’s Daytona historic event, formerly sanctioned by the AMA, would be the first under the auspices of the newly formed American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA); and lannucci felt that putting a moto-mag editor on a competitive machine in the most prestigious of AHRMA’s 12 separate classes would be an excellent way to get national exposure for this usually overlooked form of roadracing.

He was right, of course. So a few weeks later, I found myself trying to become friends with a Matchless G50—not in Daytona, however, but some 230 miles to the north at Roebling Road Raceway, a nice little roadrace circuit on the outskirts of Savannah, Georgia. Every year just prior to Daytona Bike Week, lannucci rents Roebling Road for a few days so his riders and mechanics can shake-down the team's numerous racebikes. The New York-based group works all winter preparing its machines, but doesn't have much chance to try them out before heading to Daytona; it’s kind of tough to fine-tune a fleet of roadracing bikes on the streets of Brooklyn in six inches of snow. So a brief diversion to Savannah en route to Daytona is immensely helpful to the team’s effort.

It also was quite helpful to mine, for it allowed me to get familiar with the G50—particularly its right-foot, up-for-low gearshift and left-foot rear brake—before arriving in Daytona. Hadn’t ridden a bike with that arrangement in eons. But I needn’t have worried; the Matchless was so user-friendly that I started feeling right at home on it almost immediately. Even the upside-down-andbackwards gearchanging drill became second nature after about a half-day of practice.

That was just the first of many pleasant surprises the Matchless had in store for me. Iannucci calls it his stock G50, but “stock” in his glossary of terms means something different than in mine. The 1961 machine does use the original frame, swingarm and single-overhead-cam 500cc engine, but its non-stock components include a powerful, four-leading-shoe Fontana front drum brake; a special magnesium-case, close-ratio six-speed gearbox built exclusively for Team Obsolete by Rod Quaife in England; a Gilmer-belt primary drive and dry clutch by Bob Newby Racing, also in England; and 18-inch wheels fitted with Michelin HiSports tires. And like all Team Obsolete bikes, this machine—one of only about 200 G50s ever built—is prepared as thoroughly as are most toplevel modern racebikes. Like I said, “stock.”

Still, I was really surprised at how briskly the 26-year-old engine whisked the 300-pound G50 (plus my 200-pound heft) around the Roebling Road circuit. No current Single, save for some Wood-Rotax racer special, maybe, could stay with it in stock form. More amazing was how easily and rock-steadily the bike handled, even when the 1961 chassis was stressed with the cornering forces and lean angles allowed by sticky 1987 racing rubber. No wonder G50s were considered ahead of their time back then.

Besides that machine. Team Obsolete had to ready six other bikes for Daytona, including three G50s that were a little more highly modified. One of those three would be ridden by Dave Roper, the reigning king of historic-bike racing in the U.S. Another was assigned to Iannucci’s partner in Team Obsolete, Jeff Elghanayan, who races under the name Marco Polo. Also aboard a G50 would be John Cronshaw, one of Great Britain’s top-ranked vintage-bike racers, who finished third last year at Daytona on the very same Matchless I would ride this year.

Elghanayan would also compete in the 350 class aboard a rare 1954 AJS 7R Single, nicknamed the “tripleknocker” because it has three overhead camshafts (one for the single intake valve and two for the dual exhaust valves). Just four of these AJS works racers were ever made, and Team Obsolete's is the only complete, running unit still in existence. Roper, meanwhile, would ride two other machines: a later, single-cam, two-valve AJS 7R in the 350 class; and in the Formula 750 class he would race the very BSA 750 Triple on which Dick Mann had won the 1971 Daytona 200.

But Iannucci didn't just bring Dick Mann’s racebike; he brought Dick Mann. The legendary, two-time National Champion (1963, 1971 ) has served as tuning consultant to Team Obsolete for the past several years. Mann’s vast hands-on knowledge of all aspects of racing, coupled with his expertise with G50s (which he raced with great success in the Sixties) and BSA Triples, has made him a priceless asset to the team.

He certainly was invaluable to me during my learning period with the Matchless. He helped me understand how best to use the G50’s taut chassis and fairly narrow powerband, and he kept downplaying the near-stock condition of the bike, insisting that it was the team’s most dependable racer. “It’s slower than the other G50s,” he said, “but not by very much, and it never breaks. So just go out there and wear ’em down, and you’ll have a good finish.”

By the time we got to Daytona, then, I felt ready for anything the track could throw at me. But I was not at all ready for the machinery that would greet me there. I had expected a few decently restored old motorcycles, but nothing of real bike-show nobility. As 1 stood in the tech-inspection garage, though, and eyeballed the magnificent bikes being wheeled in and out, I thought maybe I had mistakenly ended up at a concours d'elegance judging rather than a race meeting. Meticulous Nortons abounded. Spotless Gold Stars and G50s were everywhere. I saw Harley KR flatheads restored to better-than-new. Highly polished BSA and Triumph Twins that glittered in the sunlight like Las Vegas casino marquees. Pristine Ducatis. BMW Rennsports. A couple of CR750 Honda Fours. Bultacos, Benellis, a smattering of Indians. Even an immaculate Vincent 500cc Single with a full dustbin fairing. More than 200 entries in all, ranging from stone-stock to terribly trick, and there probably weren’t a dozen dogs in the lot.

My next shock came when I learned who I'd be racing against. In AHRMA programs. Matchless G50s compete in the Premier 500 class, which is the longest race of the day and the one that generally has the biggest concentration of fast riders and hot bikes. And the starting lineup for that event read like the who’s who of historic racing: Roper, Cronshaw and Polo, plus 1964 Grand National champ and threetime Daytona 200 winner Roger Reiman (who won the Premier 500 class at Daytona last year) on a potent KR Harley; David Pither, a British vintage champion on a customframed G50; East Coast BMW legend Kurt Liebmann; Alan Cathcart, CYCLE WORLD’S European Correspondent who also is an accomplished vintage racer, on another of Liebmann’s Beemers; Frank Mrazek, a 50-year-old Canadian hotshoe who rides a fast Honda 500 Twin (based on a 450) like an aggressive 20-yearold.

The list went on and on. And I remember shaking my head and asking myself out loud, “What the hell am I doing in this race?”

Right about then, everyone began warming up their engines in preparation for practice. And that was when I first became enchanted by the element that is missing in just about every other type of modern roadracing: the aforementioned variety of exhaust sounds played so magnificently by all the different types of engines. Until that very moment, I never realized just how much character roadracing has lost over the years because of monkey-see, monkey-do racingengine development.

I didn’t get much practice simply because there wasn’t much of it to get; I compiled just enough track time to figure out where the course went and which lines definitely didn’t work. Anyway, my plan was just to ride at my own pace and try to finish. With all of the fine talent and equipment in the event, I figured that finishing anywhere in the top 10 would be a major accomplishment for me.

My game plan went right out the window, though, when I blew the start of the race. I let the clutch out too quickly with too few revs, causing the revs to fall right into an absolute dead spot at around 5500 rpm—a classic case of “megaphonitis,” as old four-stroke racers call it. The engine bogged so badly that the bike almost stopped, while the rest of the field whizzed past so quickly that I felt like I was going 100 mph in reverse. I had gridded 19th out of 39 starters, but by the time I got moving and into the powerband, I was almost dead-last.

In a perverted sort of way, though, that made the race more fun for me, because I got to dice with a lot of riders. And by about Lap 7 or 8 of the 18-lap event, I had caught and passed more of them than I’d thought possible—not because of riding talent but mostly because of the sheer competence of the G50. Compared to the big, four-cylinder production bikes I’m more accustomed to riding, the Matchless banked into corners at the mere thought of turning, and I felt I could lean it over until the gas cap dragged. And although a lot of other bikes in the Premier 500 event had more powerful engines, they didn’t seem to have much of a top-speed advantage, even flat-out on the Daytona banking.

I was beginning to think I was hot stuff when Alan Cathcart blitzed past me coming down off the banking into the infield. He somehow had gotten an even lousier start than I had, and it had taken him this long to catch me. But that, too, had its benefits, because I tucked in behind his BMW and tried to keep up with him, which forced me to quicken my pace. I was just beginning to entertain thoughts of pressing even a bit harder and seeing if I could dice with him when he threw up his left hand and pulled off the track. Some mechanical gremlin had gotten the upper hand.

A few laps later, a similar situation arose when I came up behind Marco Polo. I was surprised at how quickly I had reeled him in, but when I got closer I detected the sputter of a G50 engine gone sour. Sounded electrical to me. Just as I got up beside him, he, too, raised his left hand and pulled off the track. And a few laps after that, I spotted Cronshaw’s G50 parked in the grass with a flat front tire.

Hmmm. If enough riders drop out, I thought, maybe . . ..

My delusions of grandeur were rudely vaporized by the thunder of Roper and Reiman blasting past, nose-to-tail in a take-no-prisoners battle for the lead. Rats! I had hoped to finish without getting lapped. Well, at least it was done in the latter stages of the race, and by two of the best in the business. I got some measure of consolation when I started lapping riders I had passed earlier.

As the race wound down to its final laps, I was having some serious fun. I had eased into a fairly fast but quite controllable rhythm, and the bike was working perfectly. When the checkered flag finally fell, a feeling of great disappointment came over me as I realized that my good time had ended.

I hadn’t the foggiest idea where I had finished. But, I thought to myself as I slowed down, I hadn’t ridden too badly once off the start line; and since many of the faster riders had dropped out, maybe a 10th-place finish wasn’t out of the question, despite my godawful start.

As I completed my safety lap, I saw Cathcart still sitting alongside the track, so I pulled over to ask what had happened. As I approached, he had a big grin on his face and was giving me an emphatic “thumbs-up” gesture. What’s he so happy about, I wondered.

“Congratulations,” he said, still beaming as I pulled alongside.

“For what?” I asked.

“For fourth place,’’ he said.

“Bloody good ride.”

“Me? Fourth? Are you sure?”

“Well, that’s what the announcer has been saying. You took over fourth near the end of the race.”

I was speechless. Pleased as hell, but speechless. And as I cruised back to the pits, I was convinced it was all a big mistake.

It was not. A jubilant Iannucci greeted me at the Team Obsolete pit and confirmed that, yes, I had indeed finished fourth. In truth, most of his glee was over the fact that David Roper had won, the third time that day the lanky New Yorker had done so. Reiman had thrown a chain in the closing laps while dogging Roper, and Pete Johnson, the eventual second-place finisher on a 500cc Honda Twin, was too far back to challenge for the lead. Roper had also lapped Frank Mrazek, who wound up in third place.

Still, Iannucci did seem genuinely pleased that the guest-riding journalist had managed a respectable placing-and had not wadded his expensive G50. Dick Mann offered his congratulations, too, subtly reminding me of the wisdom of his earlier “wear ’em down” advice. He just smiled his boyish Dick Mann smile and said. “I told ya.”

As I squirmed out of my leathers inside the team’s big Iveco van, I couldn’t help thinking about the wonderful time I’d had during my first encounter with historic racingand it wasn’t wonderful just because I had managed a better finish than I’d hoped. Granted, coming home fourth had added a lot to my enjoyment, but I also knew full well that most of my good fortune had been due to the bad luck of quite a few better riders on faster bikes.

No, there was much more to my enjoyment than that. For one, I learned why Matchless G50s are so highly regarded by vintage-bike enthusiasts: they're magnificent

racebikes. And Team Obsolete’s G50s are the cream of the remaining crop. I also found it refreshing to return to a type of roadracing I thought no longer existed—grass-roots, do-itfor-the-fun-of-it racing.

Out here in Southern California, at least, even amateur production racing—allegedly roadracing’s “entrylevel”-has gotten to be a fiercely competitive, dog-eat-dog affair in which most of the riders act like every race is for the national championship. Many are excellent racers who go real fast, but they don’t act like they’re having much fun. The people in historic racing, though, seem to be there for the pure sport of it all, for the camaraderie, for the neat old bikes-for the fun. It’s serious racing, yes, as all racing should be; but the riders aren’t in it for the big bucks or the factory contracts or the lap records, because none of those things are up for grabs. Instead, it’s a pure labor of love.

And in AHRMA events, there’s something for everyone, ranging from classes for the serious racer with a sizable budget to the entry-level rider with only a few bucks to spend. With such broad appeal, you have to wonder why this type of racing is usually overlooked.

But it isn’t likely to be overlooked for long. In talking to Gary Winn, the executive director of AHRMA, I learned that historic racing is the fastest-growing type of motorcycle competition in this country today. And the same phenomenon currently is sweeping across England and Japan,

I didn’t know that. But I do now, and I also know why. It's affordable. It’s fun. And the sounds alone are enough to keep people like me hooked forever.

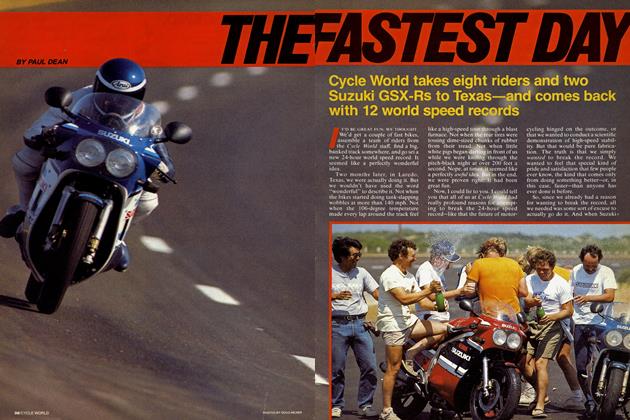

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSummer of '47

August 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1987 -

Departments

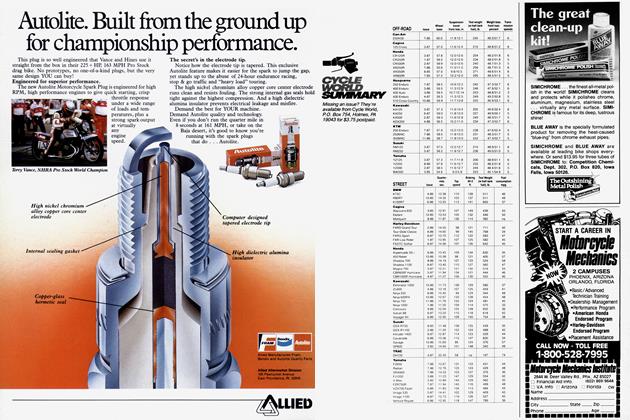

DepartmentsSummary

August 1987 -

Roundup

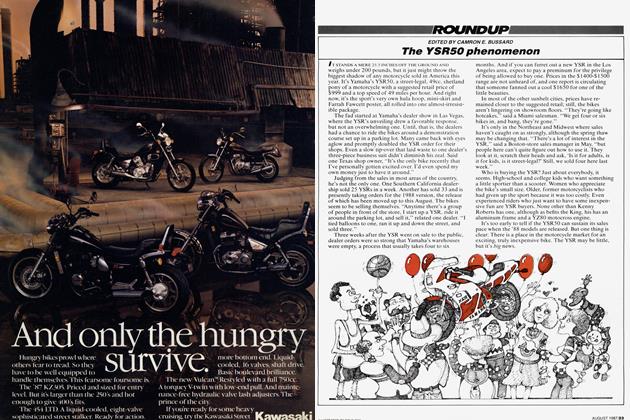

RoundupThe Ysr50 Phenomenon

August 1987 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Performance of the 400s And Into the Price of the 750s

August 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupVelocettes Live Again

August 1987