THE DAYTONA COUNTDOWN

Seven days squeezed into 57 laps

RON LAWSON

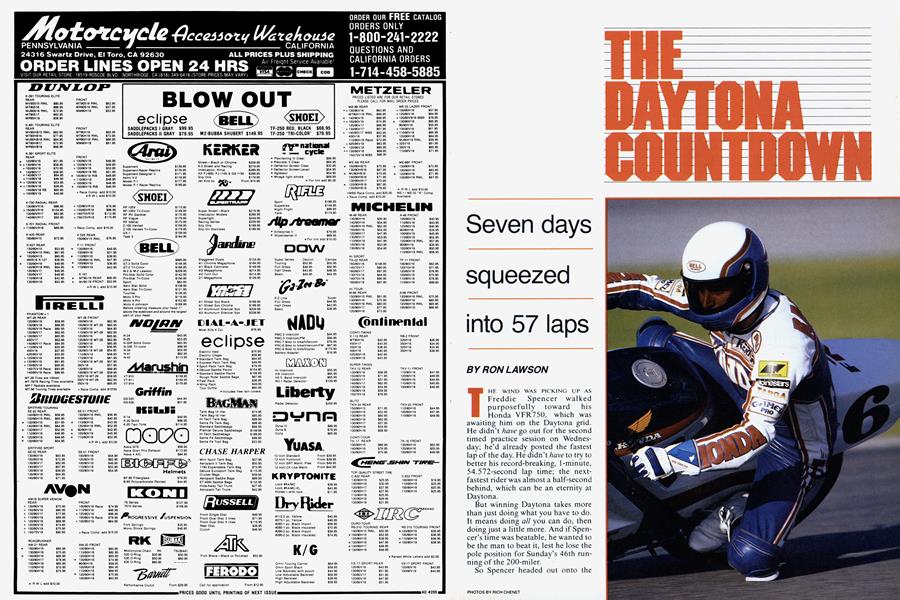

THE WIND WAS PICKING UP AS Freddie Spencer walked purposefully toward his Honda VFR750, which was awaiting him on the Daytona grid. He didn't have go out for the second timed practice session on Wednesday; he'd already posted the fastest lap of the day. He didn't have to try to better his record-breaking, 1-minute, 54.572-second lap time; the nextfastest rider was almost a half-second behind, which can be an eternity at Daytona.

But winning Daytona takes more than just doing what you have to do. It means doing all you can do, then doing just a little more. And if Spencer’s time was beatable, he wanted to be the man to beat it, lest he lose the pole position for Sunday’s 46th running of the 200-miler.

So Spencer headed out onto the 3.56-mile course, picking up more and more speed as the tires warmed. Just as he started to get serious, beginning what might have been the fastest lap any Superbike had ever turned on the famous Florida track, another rider crashed just a few feet in front of him. “I had no place to go,” Spencer would later tell Team Honda boss Udo Gietl. No place, that is, but straight into the downed bike, causing Spencer to crash, too.

When the dust cleared, the other rider, Carry Andrew of Van Nuys, California, was all right, aside from a few scratches. But Spencer was not. He suffered a fractured scapula, and within a day would be at home in Shreveport, Louisiana, under the care of his personal physician. Fast Freddie would not win, nor even

race, at Daytona this year.

But that’s typical fare for Daytona. The Sunday race that Monday’s newspaper tells you about is only a conclusion to the week-long drama that unfolds at the classic 200-miler. As each stage of practice, qualifying and preliminary racing is acted out, the results send out shock waves that affect the 200-mile main event on the last day of Cycle Week. Daytona isn’t just a two-hour race; it’s a 168-hour soap opera.

The adventure begins with lap after lap of practice early in the week. This is when riders learn the nuances of the track while working out things like tire selection and gearing. Then comes timed practice, which deter mines the pole-sitter, as well as who will sit in the first two rows at the start of the 200. But the first actual Superbike racing is seen in the two Arai 50milers held on Friday. These deter mine the remaining positions, and more important, allow the top three finishers from each of the heats to ride in the Camel Challenge, a fivelap dash that takes place immediately before the 200. There's only one thing at stake in the dash: money. The winner takes home $10,000 in cash, and the other five split $7500. All of these stages are part of the Daytona drama, and combined, they can either make or break a rider's ef fort. Satoshi Tsujimoto's week, for example, looked like it would liter-

ally go up in smoke as early as Tues day's practice. The Japanese F-i champion crashed his Yoshimura Su zuki hard in the morning session, and escaped unharmed only to crash his backup bike in the afternoon practice and have the machine burst into flames. Luckily, the Yoshimura team was able to scrounge up another bike. The next day, Tsujimoto turned a 1:55.765 lap time, the fourth fastest. And when Spencer scratched, the Japanese rider ended up starting the 200 third from the pole. Better yet, he won the first of the two Arai 50s, guaranteeing him a place in the Camel Challenge, which he would finish in third place. So for Tsujimoto, the week that had started in disaster kept getting better as the 200 approached.

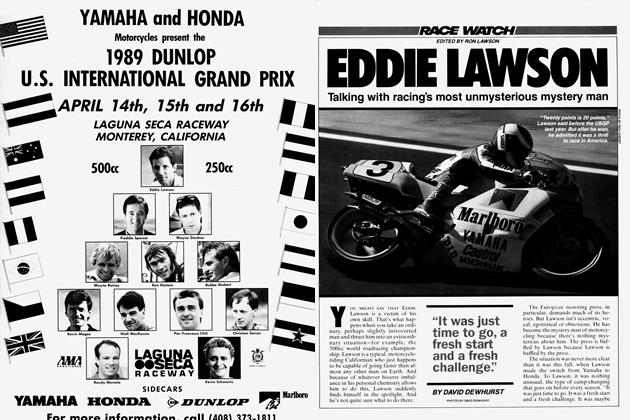

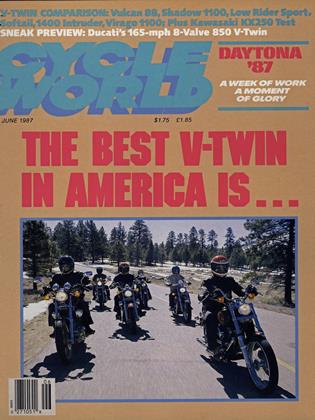

Similarly, Jimmy Filice, the rider on which Team Yamaha’s hopes were pinned, was having a week that was alternately good and disastrous. Yamaha’s presence at Daytona this year was slight—an unusual circumstance for the company that has won 14 of the last 15 200-milers there. With 500cc World Champion Eddie Lawson unable to compete because

of a sponsorship conflict (Lawson is supported by Marlboro, while the Daytona 200 gets funding from Camel cigarettes), Yamaha was putting in only a token appearance. It was a big change of pace for team manager Kenny Clark. “I’m so lowkey here I don’t believe it,” Clark reported. “Usually this place is like 10 days in the penalty box. Now I can actually see what’s going on. No Japanese technicians to get lost, no tire people to consult. After the last 14 years, it’s like a vacation.”

But thanks to Filice’s bike, Clark

still had headaches. It blew an engine on Tuesday, although the replacement motor ran well enough to give Filice a sixth-place starting berth for the 200. Then, in the second Arai 50 on Friday, Felice flew to a secondplace finish behind Wayne Rainey. Things were looking up.

It wasn’t until the day of the 200 that Yamaha’s fortunes hit a sour note. “We broke a connecting rod in practice this morning,” said a disappointed Filice. “There’s no way we can make the Camel Challenge.” So while John Ashmead was racing in Filice’s place in the Challenge, the Yamaha pit was frantic with activity—but to no avail. His hurriedly assembled FZ would be the first bike to pull out of the 200. An extremely bad engine vibration was sending warning signals to Filice, and he pulled in at the end of lap one. His Daytona, and Yamaha’s, was over.

Bubba Shobert, the junior member of Honda’s three-man Daytona effort, had equally tough luck. With Spencer out, Shobert’s role became

more crucial to Honda; and he rose to the task, qualifying fifth-fastest with a 1:56.539—virtually the same as Eddie Lawson’s record lap time in 1986. But Shobert’s experience is as a dirttracker; and while his natural talent as a roadracer is truly phenomenal, there’s no substitute for experience. Pavement experience.

Just before the start of the second Arai 50, Shobert said, “I just plan on following Wayne and seeing what I can learn.” At the start of the race, though, he wasn’t following anyone; he was going for the lead. He slipped the clutch hard off the line, and jumped out front. But within just a few turns, Shobert realized that his banzai start had burned up his clutch and cost him the race. He retired, for-

feiting his chance in the Camel Challenge. But even in the 200, Shobert would be guilty of trying too hard. Shortly after the race started, he dove into a turn too hard, crashing and ending his week. “I went into the chicane too fast, and the front end started pushing. I didn’t know what to do,” he confessed.

Shobert was not the only rider who had to endure a roller-coaster week. But going into the 200, there definitely seemed to be two good-luck stories in the making—one by Honda’s Wayne Rainey, and another by Suzuki’s Kevin Schwantz. In the case of Rainey, it was because he could do no wrong. In the case of Schwantz, it was because he simply would let no wrong get in his way. Schwantz had crashed in practice, but not until he had turned a lap time that was second only to Spencer’s. Rainey didn’t crash, and lapped the track about three-tenths of a second slower than Schwantz. The battlelines clearly were being drawn.

By chance, Schwantz and Rainey were in different Arai 50 races, so the ultimate showdown would have to wait. In the first race, Schwantz’s Yoshimura Suzuki developed a faulty ignition, and wouldn’t rev to redline. But through sheer determination and raw talent, he rode to a second-place finish behind teammate Tsujimoto. Rainey, as unstoppable as ever, dominated his race.

Both riders maintained an air of

unflappable confidence afterward. Without even a hint of worry, Schwantz said of his ignition trouble, “It’s nothing we can’t sort out.” But as he was smiling and demonstrating his confidence for the gathered press, a report of Rainey having mechanical trouble on the line of his Arai 50miler came over the loudspeaker. Schwantz suddenly went silent, listening with intensity and betraying the pressure he was really feeling.

Rainey’s problem was a sticky throttle cable, but his crew fixed it on the line. He then blew to a convincing victory. Afterward, Rainey was just as cool as Schwantz had been. “That was a comfortable pace. I wasn’t really pushing because no one was pushing me,” he said. But then he turned to a Honda technician and asked quietly, “Which race was faster? Mine? By how much?” Under his confident exterior, Rainey, too, was feeling the pressure.

This battle of nerves erupted into a one-on-one conflict when the two were matched against each other for the first time in the Camel Challenge. Rainey had the pole, and he got the lead on the start. Schwantz tucked in right behind, and the two set a blistering pace that slowly opened ground on Tsujimoto, Roger Marshall, John Ashmead and Reuben McMurter.

At first, Schwantz made a few attempts to pass Rainey. But the pace was very fast, and that gave rise to a dilemma that will surely plague the Camel Challenge for the rest of the season. Should Schwantz go all-out, risking a crash that would surely put him out of the 200? Or should he follow Rainey, hoping for a mistake, saving his best riding for the big race? Schwantz apparently chose the latter, going the same speed as Rainey, but never making a serious attempt to pass him.

That strategy changed in the 200, though. This time, Schwantz had the pole position and took the lead on the start. But Rainey passed Schwantz, then Schwantz passed Rainey. And while the two of them continued to trade back and forth, everyone else once again was left behind. Their lead grew even more when Shobert crashed, causing Tsujimoto to slow down momentarily.

As the race progressed, though, it clearly was Schwantz who wanted the win more. He began to pull away from Rainey, and when they got into lapped traffic, he called on whatever magic he had been using all week to slide in and out of lappers, losing virtually no time in the process. The slower riders seemed to baffle Rainey. “There were riders turning where I didn't think they should turn,” he said later with an uneasy laugh. “I bumped into a few.”

Then there was the matter of tires. Schwantz had gone to harder-compound Michelin tires for the 200, while Rainey stayed with the same type of Dunlops on which he had qualified and run the Camel Challenge. Rainey had to change tires on his first pit stop; Schwantz didn’t. Add 10 seconds to Schwantz’s already-growing lead.

Finally, Rainey began to figure out the slower riders. His passing improved and he was beginning to nib-

ble away at Schwantz’s 18-second lead. It looked like it might be a race after all.

By lap 34, Schwantz was still weaving in and out of the lapped riders, if not with the greatest of ease, at least quickly, still using the Schwantz magic to its limits. But going into the chicane on that lap, his bag of tricks came up empty. A fierce tailwind was pushing everyone into that turn faster than usual, forcing them to brake earlier. Schwantz came up to his usual braking point and thought that he might be able to pass one more backmarker before entering the turn. But he couldn’t, and lost the front end, crashing hard. No more lead, no more magic, no more Daytona for Kevin Schwantz. Rainey

rode by, seeing Schwantz nursing a badly injured finger, and immediately slowed his pace. He had Daytona won. The only person who could beat Rainey at that point was Rainey himself.

Tsujimoto took the lead briefly when Rainey pitted, and then relinquished it when he pitted himself. And for the rest of the race, the only drama was in seeing how many riders Rainey could lap. When he passed third-place Doug Polen—the Texan who was putting in an incredible ride on a lightly modified GSX-R750 that had about a 20-horsepower deficit on the leaders—Rainey had lapped everyone except Tsujimoto at least once.

And that’s how it went into the books. Rainey passed the checkered flag in what turned out to be a relatively dull finish. For the latter part of the race, spectators were making trips to the hot-dog stands, buying Tshirts for the kids and even heading out to the car to get a head-start on

the traffic. Because the race had ended on lap 34.

But Daytona is almost always like that. The 200’s finish has rarely been close, which traditionally is the case with most long races.

And after all, the Daytona 200 is one of the longest of the long. It lasts a whole week. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Crash Course In Career Counseling

June 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMil-Spec Motorcycling

June 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart