THE RIDE

JOHN SURTEES

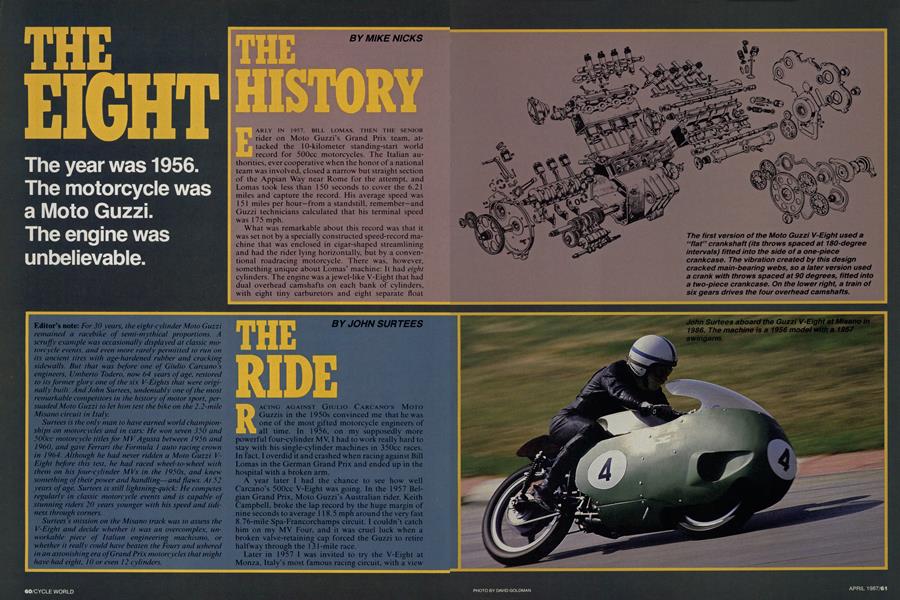

Editor’s note: For 30years, the eight-cylinder Moto Guzzi remained a racebike of semi-mythical proportions. A scruffy example was occasionally displayed at classic motorcycle events, and even more rarely permitted to run on its ancient tires with age-hardened rubber and cracking sidewalls. But that was before one of G iu lio Carca no's engineers, Umberto Todero, now 64 years of age, restored to its former glory one of the six V-Eights that were originally built. And John Surtees, undeniably one of the most remarkable competitors in the history of motor sport, persuaded Moto Guzzi to let him test the bike on the 2.2-mile Misano circuit in Italy.

Surtees is the only man to have earned world championships on motorcycles and in cars: He won seven 350 and 500cc motorcycle titles for MV Agusta between 1956 and I960, and gave Ferrari the Formula I auto racing crown in 1964. Although he had never ridden a Moto Guzzi VEight before this test, he had raced wheel-to-wheel with them on his four-cylinder MVs in the 1950s. and knew something of their power and handling—and flaws. At 52 years of age, Surtees is still lightning-quick: He competes regularly in classic motorcycle events and is capable of stunning riders 20 years younger with his speed and tidiness through corners.

Surtees's mission on the Misano track was to assess the V-Eight and decide whether it was an overcomplex, unworkable piece of Italian engineering machismo, or whether it really could have beaten the Fours and ushered in an astonishing era of Grand Prix motore veles that might have had eight, 10 or even 12 cylinders.

RACING AGAINST GIULIO CARCANO’S MOTO Guzzis in the 1950s convinced me that he was one of the most gifted motorcycle engineers of all time. In 1956, on my supposedly more powerful four-cylinder MV, I had to work really hard to stay with his single-cylinder machines in 350cc races. In fact, I overdid it and crashed when racing against Bill Lomas in the German Grand Prix and ended up in the hospital with a broken arm.

A year later I had the chance to see how well Carcano’s 500cc V-Eight was going. In the 1957 Belgian Grand Prix, Moto Guzzi’s Australian rider. Keith Campbell, broke the lap record by the huge margin of nine seconds to average 118.5 mph around the very fast 8.76-mile Spa-Francorchamps circuit. I couldn't catch him on my MV Four, and it was cruel luck when a broken valve-retaining cap forced the Guzzi to retire halfway through the 131-mile race.

Later in 1957 I was invited to try' the V-Eight at Monza, Italy’s most famous racing circuit, with a view to joining the team as a factory rider for the 1958 season. But the test didn’t take place: I received a phone call just days beforehand informing me of Moto Guzzi's withdrawal from competition.

So I had to wait nearly 30 years before satisfying my curiosity about this extraordinary motorcycle. And even on the morning of the scheduled test session at the Misano circuit, when Moto Guzzi’s little Fiat van drove into the pits, I somehow doubted that they had actually brought the bike. Was I going to get a ride on that tantalizing V-Eight at last?

But there it was, superbly restored to a specification almost identical to its condition for its last competitive appearance at the Italian Grand Prix in 1957. Umberto Todero, the bike’s savior, was there too; the same smiling. bubbly man I remembered so well from the 1950s, and as excited as I was at the thought that the Eight was going to run again. The only major change he had made was to substitute a 19-inch rear wheel for the 20-inch rim the bike had originally used. Suitable 20-inch tires are no longer made, so Todero had fitted 19-inch Pirelli Phantom tires of 3.5-inch widths. In 1957 the Eight ran on a 3-inch-wide front tire and a 3.25-inch rear.

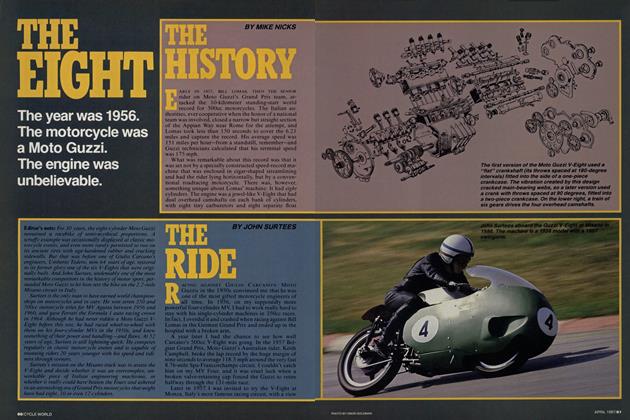

A young motorcyclist of today who knows nothing about the classic era wouldn't find it hard to guess that the V-Eight had come from Italy. It is a work of art just to look at. The engine is dominated at the front by the radiator for the one-gallon cooling system (to prevent the rear bank of cylinders from overheating), at the top by the forest of carburetors, and on the right by the massive, Y-shaped casing that covers the train of six cam-drive gears.

Yet the machine is incredibly compact for an eightcylinder motorcycle. It’s less than a half-inch wider across the flanks of its fairing than Carcano’s 350cc Single racer, and the wheelbase is only 56 inches. The dry weight of the 1956 V-Eight was 340 pounds, although the 1957 version-with a magnesium fairing and engine cases replacing the earlier aluminum components—was said to weigh only 300 pounds.

At Misano, Alfio Micheli, a Guzzi factory tester who had helped with the rebuild of the Eight, took the machine out for a couple of laps to run-in new piston rings and ensure there were no oil leaks or other problems. Then it was my turn to sample the only eight-cylinder racing motorcycle ever made.

I b~rb1ed o~t of the pits at around 3000 revs with the engine running on anything between six and eight cyl inders. I was under strict instructions not to let the water temperature exceed 185 degrees or run the en gine past I 0.000 rpm, so my initial lap was just a get ting-to-k now-you one-a touch of the brakes to see how they reacted, up and down through the five-speed gear box to check the change action (the last thing I wanted to do was miss a shift), all the time keeping to about 6000 revs, with the engine still burbling on seven or eightcylinders.

immediate impression was of the bike’s excep ride quality. Misano is a bumpy circuit, and there lot of nasty ridges on the racing line which often luce wheel patter. But the Eight seemed oblivious to these problems as I took it to 7000 rpm on the second lap and was rewarded with that unmistakable V-Eight sound. It’s very different from the MV, Gilera and Benelli four-cylinders, which are so much louder. The nearest note I recall to this came from one of the first

Ferrari V-Eight race cars in the early Sixties before we went to a megaphone exhaust system.

Now I coul&start increasing~the pace. At 7500 rpm the machine was carbureting nicely and obviously start ing to pull on all eight cylinders. Then. at 8000 rpm. there was a sudden surge of super-smooth power. The engine really takes off at this point, so I had to have a quick dab at the gear pedal to ensure that I didn't ex ceed our agreed-upon test rev limit. ____________~______1 I I `~ r~i~r~ -"

In its day, the engine was redlined at 1Ï Todero told me there was no fall-off in powe 13,000. Here was the secret of the V-Eight’s tremí dous speed: With even carburetion from 7000 rpm, real urge from 8000 to 13,000 rpm, the Eight rider could be sure of finding power every time he went up a gear. Carcano specified a six-speed gearbox for his first V-Eight. fearing that he had created a machine with a viciously narrow powerband. But when he realized the broad spread of power the engine was giving, he went to a four-speed gearbox to save weight and add simplicity. The five-speed box fitted to the test machine was a compromise between the two extremes.

Despite its apparent complexity, the Guzzi demands no more physical effort from the rider than a 250cc machine. Carcano knew that a V-Eight layout would keep the engine narrow and its mass centrally located.

The left-hander in the middle of Misano’s fast back straight is a good test of any machine’s handling. The V-Eight went through impressively, the front fork giving only a slight, sharp shock at the moment of turning. The leading-link fork that Carcano fitted to so many of his racing machines is responsible for much of the VEight’s superb ride quality, and has the added advantage of resisting fork plunge under braking, without the complication of the additonal mechanical, hydraulic or electronic systems found on many modern roadracing bikes.

I wasn't immediately impressed by the front brake, however. It consists of a pair of single-leading-shoe drums 8.7 inches in diameter—typical 1950s’ equipment—but the slippery dustbin fairing allows the bike to glide on, even when the throttle is shut. And the normal racing habit of sitting well up at the end of a straight to act as an air brake has no effect when you’re sheltered behind a dustbin.

A leading-link fork does, however, give the rider the benefit of a properly effective rear brake. Without the massive weight transfer permitted under braking by a telescopic fork, the V-Eight’s rear wheel stays firmly in contact with the ground, and its single drum is probably the best back brake I’ve ever experienced. Carcano helped it work better by using a fully floating brake plate with the torque arm attached to the frame.

Unfortunately, there is also a disadvantage in leading-link forks: They transmit slightly less information from the road suface than that often-criticized compromise, the telescopic fork. The leading-link type copes beautifully with braking, turning and the general ride, but that little element of stiction that the V-Eight produced on Misano’s fast left-hander is typical of their performance. To handle the Eight at 100 percent, you would have to be that much more sensitive to the machine than the rider of a bike with a telescopic fork.

In these days of small-diameter, wide-section wheels on racing motorcycles and many road-going sportbikes, Carcano’s choice of a 20-inch rear wheel with a narrow tire must seem odd; even in the 1950s, his rival designers had moved to 19-inch rear tires. But Carcano’s thinking was sound. He preferred to achieve a good contact patch by means of tire diameter rather than width. What is usually forgotten when wheel sizes are discussed is that a very wide tire generates lift, just like an aircraft wing, as it moves along the road surface. Could this be the reason why some of today’s Grand Prix bikes have actually gone back up in tire diameter from 16 to 17 inches? Weight also counted in Carcano’s reasoning, as every ounce saved was an important factor to him, and he would not have wanted to waste it on a wider, heavier tire if there was no proven advantage.

Would the V-Eight have beaten the Fours if its career had not been prematurely curtailed by the mass Italian retirment from racing at the end of 1957? Well, it did beat the Güeras and the MVs in Italy in 1957, although it never won a world championship Grand Prix.

Undeniably, the bike suffered its share of breakdowns, but more development would surely have found reliability. And much more power could have been obtained from the engine. The eight separate exhaust pipes, each only an inch in diameter, were Carcano’s first effort in this area, and I know from my experience with eight-cylinder car engines that big gains can be obtained from other exhaust layouts.

If Carcano and Moto Guzzi had been able to continue with the V-Eight, they probably could have achieved 100 bhp and 18,000 rpm by the early 1960s. A six-speed gearbox would have been necessary then, to cope with the inevitably narrower power band. And Carcano would have had to use wider tires: In the Fifties, we had already abandoned traditional tram-line riding styles, and were using the power of the Güera and MV Fours to drift through corners in the modern manner.

There is an old car-racing saying that a good Eight will always beat a good Four, and I think that would have applied to the Guzzi. We’ll never really know, of course. But one thing is clear about the V-Eight. It was, and is, a fantastic achievement, and we are fortunate that Umberto Todero’s skills have saved the V-Eight for motorcyclists of this and future generations to admire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

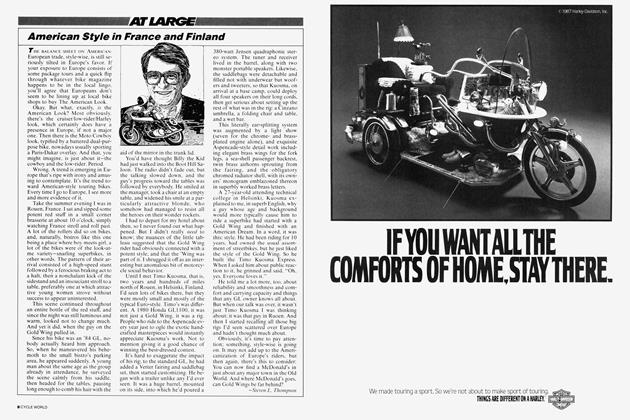

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart