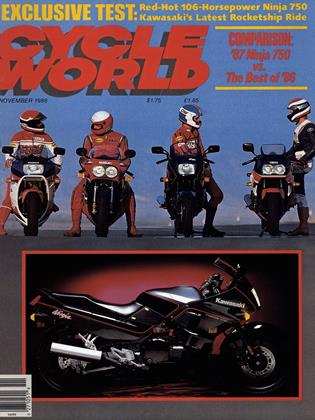

Comparing the 750s

The Ninja is the newest; is it the best?

At top speed

Seven-fifties are it. Because of legal limits on displacement in Japan, because of 100-horse power restrictions in Germany and Holland, because of 750cc Superbike racing in the U.S., 750s have become the world's premier sportbike class, the one that no Japanese manufacturer can ignore. Now, with the introduction of the Ninja 750, no manufacturer is ignoring the class. There's a full complement of contenders for 750 sportbike honors, perhaps for the first time ever. That's reason enough to compare Yamaha's FZ, Suzuki's GSX-R and Honda's VFR to Kawasaki's latest Ninja. We've looked at how they perform in some specific performance tests, and then in more general road use. One caveat is required, however. Only the Kawasaki is a 1987 model (though an early release); the others are 1986 versions. So these comparisons reflect performance rankings onl y as of early fall, 1986. Even as high as these standards are, they may be raised further before the 1987 model year is over.

MORE THAN 30 YEARS AGO, A VINCENT BLACK Lightning, tuned to that era's limits for metal and oil, bellowed across the Bonneville Salt Flats. As it streaked past the timing lights, it set a new U.S. speed record for motorcycles: 150 mph. In 1986, two 750s, the VFR and the Ninja, will match that 150-mph top end, but without the strain. They do it in showroom stock tune, with mirrors attached, while meet ing 80 dB noise limits. Yamaha's FZ. at 149 mph, runs right with them, while Suzuki's 139 mph GSX-R is still a fast three-quarter liter machine.

Perhaps more amazing than the speeds these 750s can reach is the poise and stability they have near two-and-ahalf miles per minute. The Honda and Suzuki are dead stable at their highest speeds. The Ninja and the FZ only hintat moving about above 140 mph.

At the dragstrip

AMLRI'ANS FIAVI LONG J1~LX~ED SPORI1NG MOTORCY cles on their quickness in covering 1320 feet. To establish which of these four would win that con test, and to push their times down to their physi cal limits, we enlisted the services of drag-race ace Jay Gleason and Carlsbad Raceway. Because of Jay's light weight and incredible skill, these times are better than the (Y('LF WORE 1)-stafi-generated numbers found in our previ ously published tests.

First place was a tie: the Yamaha FZ and the Suzuki

GSX-R both stopped the lights in 11.10 seconds. The Suzuki was traveling slightly faster at the end of the quarter, 121.45 mph versus the FZ’s 120.00 mph, but the most significant difference was in the ease of riding these two bikes. “The GSX-R,” said Gleason, “is the most difficult bike to launch I've ever ridden.” He explained that the Suzuki's clutch has a very narrow engagement span, and that it was all too easy to bog the engine with too quick a clutch release, or to over-compensate with more throttle and spin the rear tire. Accordingly, his times on the GSXR varied by a tenth of a second or so run-to-run. which was less consistency than he prefers. The FZ, in contrast, couldn’t have been more predictable: Gleason's last three runs all had perfect, front-wheel-skimming launches, and all three produced the same 1 1.10-second time.

The Honda VFR launched almost as easily, but finished half an eyeblink slower at 1 1.17 seconds and 120.80 mph. The rest of that eyeblink back came the Ninja with a 1 1.20second run at 121.78 mph. A power deficit didn't put the Ninja there: its clutch did. The Ninja's fastest run was its second, on a still-fresh clutch and while carrying a full fuel load. The other bikes produced their best times on their second set of runs, after they had been relieved of twenty five pounds or so of gasoline. But while perfectly adequate for any street-use. the Ninja’s clutch wasn't up to to the extreme abuse imposed by multiple, full-throttle,

8000-rpm dragstrip launches; it became grabbier on each successive run, and cost Gleason time.

On the racetrack

DESPITE four sportbikes THEIR RACY, are intended RAKISH APPEARANCES, for street use. THESE But there’s almost a contradiction there; All four perform so well that it’s simply not possible to plumb their limits on the street. For that, a racetrack is a necessity.

In this case, limit-plumbing required the use of Willow Springs Raceway. To make certain we would be testing bikes and not tires, we fitted all four machines with raceproven Michelin Hi-Sports. To ensure that the rider tested the bikes and not the reverse, in-house racer Doug Toland—who has held production-class lap records at Willow—did the timed laps. Feature Editor David Edwards and Technical Editor Steve Anderson came along as controls; both are good street riders more than racetrack aces, and were there to see if their perceptions differed from those of a national-class rider.

The slowest 750 was the most surprising: the Suzuki GSX-R with a 1:36.8 lap time. This racer-replica was let down by its rear shock, w'hich faded away after the first timed lap. Toland liked the GSX-R’s non-twitchy steering

feel and good brakes, but simply couldn’t go faster without rear-suspension damping. In fact, people who race the GSX-Rs almost universally change to an aftermarket rear shock. As for the two editors, both would have liked more leverage than provided by the Suzuki’s clip-ons; they are joined in this by Kevin Schwantz, who runs higher and w ider bars on his Yoshimura Suzuki Superbike than come standard on GSX-Rs.

Third fastest was the FZ Yamaha, which cut a 1:36.1. For Toland, the FZ was a little twitchy, shaking its head over a fast, turning rise. But he liked its power out of corners, and the ease with which it handled left-right-left transitions. Anderson and Edwards liked it more: At their slower pace, the FZ felt reassuringly stable, and its wide powerband meant they had more leeway in gear selection.

A second-best 1:35.6 was set by the Ninja, and Toland thought it felt better than the Yamaha as well. Never letting it fall below 8000 rpm, he was impressed with its acceleration, and also with its front brake, which required the least effort and offered the best feedback. The Ninja's front end shook over the fast rise worse than the FZ’s. but that didn't upset Toland; he liked its stability under transitions on the rest of the track, and the way the front tire stuck instead of pushing. He also thought the Ninja would respond well to suspension tuning, particularly stiffer fork springs. The two editors liked the power and the brakes as

well but were less impressed by its quick steering, and the way it moved around the most on the fast corners. While the Ninja didn’t scare them, they preferred a more stable platform.

Fastest of the fast was Honda’s VFR, with a 1:34.2. With Toland aboard, the exhaust header pipes touched hard on both sides, which required rear spring preload to be boosted to the maximum setting. That left the back end over-sprung and the front fork relatively soft, but the VFR still felt much more stable than either the Yamaha or the Kawasaki. It also felt bigger, and the front brake required more lever pressure, but neither factor slowed it down. The editors concurred, finding the Honda the easiest to ride and most stable.

On the street

THE FINAL TEST WAS A TWO-DAY, 500-MILE STREET ride that covered fast and twisty mountain roads, slow and winding canyon roads, and a fair span of JI’. interstate highways. This was the acid test for these sportbikes.

The first to fall out of the running was the GSX-R. Wonderfully competent in most performance categories, it simply is not a very good streetbike. Its bars are too low, its footpegs too high: We could always recognize the GSXR rider on the freeway by his left elbow planted on the gas tank, trying to relieve some weight from his arms. In hot weather he would also be baking from the heat pouring off its engine.

Little, if any, performance advantage has resulted from the Suzuki’s racer-replica aspects. On tight roads, the clipons offer insufficient leverage to toss the Suzuki about; riding hard becomes hard work. The Suzuki’s topweighted powerband requires concentration on gear selection as well. That’s fine if you’re in a mood to attack, but the other 750s can go as quickly in attack mode without falling as far off the pace in cruise.

Once past the GSX-R, the rankings became much more difficult. By a small margin, the Yamaha earned third place. Once again, the motorcycle was very competent, and its engine marvelous. But the Yamaha was let down by an uncomfortable seat, an occasionally hair-trigger throttle, brakes that needed more feel, and by its overall greater weight. The FZ is an excellent bike, but these small faults place it behind the Ninja and the VFR.

Between those two, though, any decision blurs. As a pure street machine, the Ninja may have the slightest of edges. It has the best seat, the best control of engine heat, slightly more mid-range power, and light, quick handling that makes it feel more like a good 600 than a 750. The VFR feels like a larger motorcycle, with a noticeably higher center of gravity. At times, though, its slower handling can be reassuring. But all these differences between the VFR and Ninja are subtle.

One that isn’t subtle is engine character. The Ninja has a wailing inline-Four, always urging its rider on; the VFR, with its 180-degree V-Four crank, has a syncopated beat that can be relaxing at cruise, or soul-stirring as the revs rise. On this one subject there was unanimous agreement: The VFR engine simply felt the best.

In the end, both the VFR and the Ninja are so good that choosing between them almost comes down to taste. Do you like a V-Four beat? Do you like a larger-feeling machine? Then it’s the VFR for you. Do you like to pile on miles in sport-touring? Do you like Kawasaki styling? Then the slicker, slightly more comfortable Ninja may be your bike.

Whatever your decision, you can’t lose. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

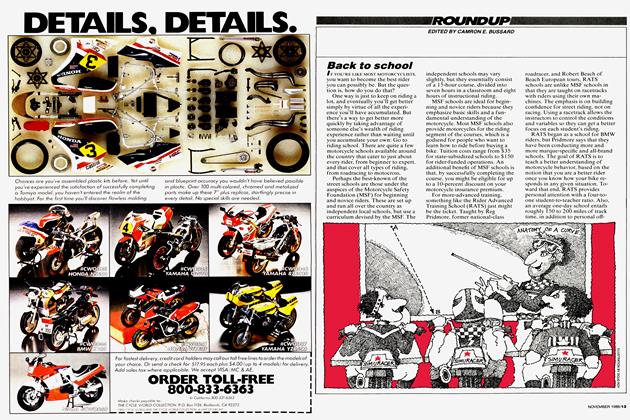

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart