VETTER'S BIKE-TO-BIKE INTERCOM SYSTEM

CYCLE WORLD EVALUATION

AN ALTERNATIVE TO PLAYING 55-MPH PANTOMIME QUIZ

ANY TIME YOU GO RIDING WITH A FELlow motorcyclist, what the two of you end up with, to paraphrase Strother Martin in Cool Hand Luke, is your basic failure to communicate. He waves his hands, you gesture back, and neither of you is quite sure what the other is trying to say. But Vetter’s Bike-To-Bike Intercom attempts to solve that dilemma by making communication between riders not only possible, but as easy as breathing.

Vetter’s system requires no wires, cables or hand-utilized switches, only two nine-volt batteries and at least two full-face helmets. Installation takes about 30 minutes. You attach one of the adhesive-backed transmitter units to the back of each helmet, and similarly glue a small Velcro pad to the inside of each mouth guard. The microphone is held to the pad with mating Velcro. A pre-cut foam mold secures the speaker in either ear hole of the helmet, and to complete the installation, you slip a terry cloth chinguard onto the bottom of the helmet to shield the microphone from wind turbulence.

Once you get all of this together, everything works quite simply. The unit is designed with a Voice Operated Transmitter (VOX), so all you have to do is speak; the VOX does the rest, switching from receiver to transmitter automatically. When you and your friend are riding close together, or if a passenger on your bike is wearing the other unit, you rotate the transmitter on both helmets counterclockwise. For distant communication, you rotate the units clockwise. And the further you rotate the dial in either direction, the more you increase speaker volume and decrease microphone sensitivity. Finding the right balance, however, depends on the constantly changing environmental conditions, such as wind and traffic noise.

When you're stopped, the units work well, but the sound crackles more and more as your speed increases. The range on the “near” position is roughly 10 car-lengths, and in the “far” position about one-half mile. The sound breaks up when you out-distance the transmitter.

There are, however, a couple of problems with the system. The first is that there is no way to disconneet the microphone without turning off the whole unit. So every time one rider sneezes, coughs, hiccups or clears his throat, the other rider unceremoniously gets to share the experience. Also, the terry cloth shield can constitute enough of an air-flow restriction to make riding in hot w'eather more uncomfortable. Yet even with the shield in place, the wind activates the unit when no one is speaking, resulting in an irritating outburst of static followed by the hiss and click that occur every time a transmission is complete.

Not only that, the receiver picks up all kinds of alien broadcasts. Highvoltage lines cause so much distortion and interference that you have to turn the units off when riding along or under a powerline. And riding in town is like listening to a rapid spin of an AM dial: You pick up jumbled static and even bits of CB radio conversations.

Ultimately, we concluded that hearing too much of what we didn't want to hear overcame any advantages of hearing what we did want. We also chose to turn the units on only when we had something important to say, rather than leave them on all of the time. If Vetter's system could filter out the interference, and would allow the rider at least some control of the mike, it would be more than a practical item; it would be essential. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

August 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

August 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1985 -

Roundup

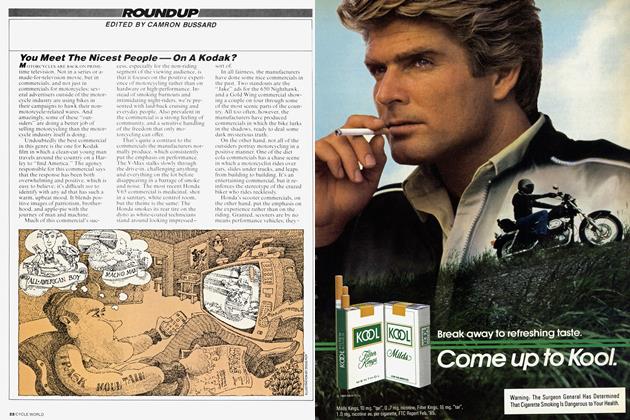

RoundupYou Meet the Nicest People—On A Kodak?

August 1985 By Camron Bussard -

Roundup

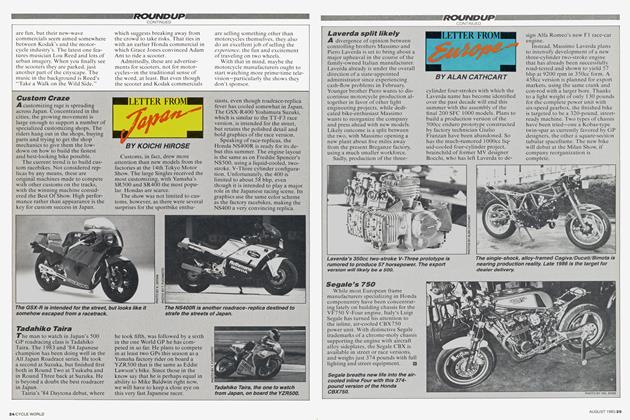

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

August 1985 By Alan Cathcart