THE OTHER SIDE OF THE TRACKS

The case 0f Scott Gray vs. Daytona

RON LAWSON

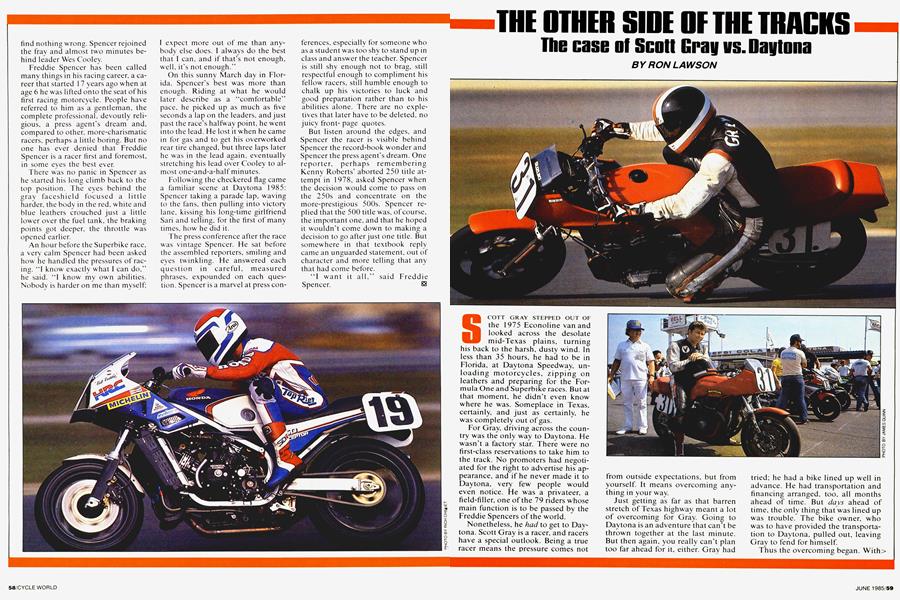

SCOTT GRAY STEPPED OUT OF the 1975 Econoline van and looked across the desolate mid-Texas plains, turning his back to the harsh, dusty wind. In less than 35 hours, he had to be in Florida, at Daytona Speedway, unloading motorcycles, zipping on leathers and preparing for the Formula One and Superbike races. But at that moment, he didn’t even know where he was. Someplace in Texas, certainly, and just as certainly, he was completely out of gas.

For Gray, driving across the country was the only way to Daytona. He wasn't a factory star. There were no first-class reservations to take him to the track. No promoters had negotiated for the right to advertise his appearance, and if he never made it to Daytona, very few people would even notice. He was a privateer, a field-filler, one of the 79 riders whose main function is to be passed by the Freddie Spencers of the world.

Nonetheless, he had to get to Daytona. Scott Gray is a racer, and racers have a special outlook. Being a true racer means the pressure comes not from outside expectations, but from yourself. It means overcoming anything in your way.

Just getting as far as that barren stretch of Texas highway meant a lot of overcoming for Gray. Going to Daytona is an adventure that can't be thrown together at the last minute. But then again, you really can’t plan too far ahead for it, either. Gray had tried; he had a bike lined up well in advance. He had transportation and financing arranged, too, all months ahead of time. But days ahead of time, the only thing that was lined up was trouble. The bike owner, who was to have provided the transportation to Daytona, pulled out, leaving Gray to fend for himself.

Thus the overcoming began. With> the help of his sponsor, Jim Williams, Gray pieced togther another Superbike in a matter of days. He borrowed a well-used van—one that purportedly had made the Daytona trek years earlier hauling Eddie Lawson—and he slowly reassembled the shattered remains of his plans.

The van was discouraging in itself. Despite its heritage, it was less than ideal for the trip. The '75 Ford had been sitting in a backyard for nine months, and now contained cobwebs, bugs, even several pounds of dried-up dog food. It didn't look like it could travel across the street, much less across the country. But it would have to carry Gray, his crew, his bike, his equipment and whoever he could get to share expenses, all the way from Santa Rosa, California, to Daytona Beach. Florida.

That trip would be crowded as well as long. The van would also carry Vince Costa, another racer driven by the same need to compete at Daytona, and Gray’s two mechanics, Paul LeBrett and Karl Wahlman. Then there was T.J. and his wife, Baby. T.J. is a biker at heart, a 200pound, Harley rider who had to see, feel and taste for himself Daytona’s famous gathering of the H-D family. So T.J. agreed to act as Costa’s wrench, paid a third of the expenses, and loaded up his FLH between the two superbikes on the trailer. T.J. and Baby brought the van’s occupancy up to six people, four motorcyles (including Fuzzy The Moped), a green lounge chair, four extra engines, assorted toolboxes, sleeping bags and suitcases, and a foam-rubber pad to act as a bed. They were ready for Daytona.

Whatever happened on the trip, they would overcome it: This they knew after already repairing so many plans. So as Gray walked around the gasless van on that desolate Texas highway, there was no frustration; he simply focused on how to overcome and continue. After calculating the options and his time schedule, Gray unloaded Fuzzy The Moped, strapped on a five-gallon gas can, and sputtered down the road in search of the nearest town while Vince, Karl, Paul, T.J. and Baby waited.

Before reaching their destination, they would run out of gas again—the van had a broken fuel gauge and a hearty thirst for petrol—they would endure severe fog in Mississippi and add uncounted quarts of oil to the van's weary engine. They would switch off driving, while whoever was trying to sleep in the green lounge chair or on the foam rubber pad would be periodically slapped in the head by a hanging garment bag. They would even unload the FLH and alternately ride it behind the van, just for diversion on the long road and as relief from the close living quarters. Finally, after nearly 4000 miles and 67 hours of driving, they reached the promised land. Now the really tough part would begin.

Monday morning at nine a.m., Gray coasts off the track, gets off his Suzuki and begins the long push back to the pits. The cam chain had broken. starting a disastrous chain-reaction of snapped rocker arms, bent valves and broken pistons. Within a fraction of a second, the expensive, highly tuned GS750 engine had transformed itself into so much twisted and fused scrap metal.

Gray isn’t fazed. “One down, three to go,” he grins, gesturing toward the spare engines lined neatly in a corner of the rented garage.

The next two days are spent feverishly trying to make one of the spares run properly. It resists. Alternately, it will run on two cylinders, or three cylinders, or not at all, and time is running out. Thursday morning and Friday morning offer the only qualifying sessions for the Superbike race, and Thursday afternoon is Gray’s only shot at a spot in the F-l race. Like most privateers, he needs to run in both races—not for extra profit, but to minimize the loss for the trip.

As Thursday’s qualifying session comes to a close, the Suzuki is still resisting, so the Superbike qualifying attempt will have to wait until the last session on Friday. Finishing up the machine for Formula One qualifying takes top priority now. The problem is traced to the ignition, and an entirely new system is bolted in place. Meanwhile, the first group of riders, the group that Gray is supposed to be in, takes to the track. But a sympathetic track official assures Gray that he can go with the third group. When the Suzuki is finished and rushed to the starting grid, there are the expected mix-ups (“Sorry, you missed your session. Who said you could go with this group?”), but Gray finally makes it onto the track in time to get in just three laps of practice.

The problem now is that in order to qualify for Daytona’s F-l race, a rider, during his qualifying session, has to average at least a minimum designated speed for three continuous laps. So Gray, whose total Daytona experience consists of the six laps he took on Monday before ruining his first engine, now finds himself on the unfamiliar banking once again, riding a machine that was pieced together overnight and that has never run for more than a few minutes. Every lap has to count.

Every lap does. He can only qualify for the second wave, but he does qualify. He overcomes.

On Friday morning, things are looking up. Gray goes fast for Superbike qualifying—fast enough, in fact, to make the first wave. But first comes the F-l race.

“By then I have almost 20 laps of practice on the track and I'm ready, I’m racing,” Gray says later. “The first wave leaves and it seems like forever waiting for the second wave to get flagged off. But I get a pretty good holeshot, I’m third, and I pass second and first, so I’m leading the second wave and everything is looking good, everything is perfect. Somewhere about the eighth lap or so, Spencer comes around to lap me. It was great. You see, with no practice all week, I had just been watching Spencer, and consequently I was using all his lines. On the banking I’m the only one in his way. He shifts to the inside and just flashes by. By the time I get to the braking marks for the chicane, he’s through the chicane. Then he just says ‘see ya,’ and it’s like he has three extra gears. But everything’s still going good for me. The only problem is my left boot. The sole starts coming off, and this big flap is dangling under my shifter.”

Paul, one of Gray’s pit crew, recalls how the boot-sole problem was dealt with. “Scott comes roaring into the pits and we’re all ready to gas him up, but he’s screaming about his boot. I look around and there is nothing to cut that flap off with, so I just grab it and start yanking. It’s a miracle that I don’t break his leg. But I tear the flap off and Scott takes off, full of gas and with nothing but his sock between him and his footpeg—which was missing the rubber part anyway.”

“Now we’re in 28th position and I’m pumped,” Gray recounts. “Everything is working great. But then the bike starts running a little funny. Then it’s running even more funny. Then it quits.” One lap after gassing up, Gray comes back into the pits, his second engine blown. Nothing can be done; his race is over.

Daytona never leaves enough time for regrets, or for feeling sorry, though. There’s only enough time to get ready for the next race. The F-l race isn’t even over before Gray’s crew starts pulling out the Suzuki’s motor. The Yoshimura team let Gray borrow one of its engines for the 200, and Gray and company spend all Saturday preparing the bike.

Sunday is the 200. That’s the race, Daytona’s reason for being. To a privateer like Scott Gray it makes little difference if the 200 is F-l or Superbike: He’ll run the same bike in either case. And the factory riders will go faster no matter what. How much faster is the only difference.

But once the race is underway, the factories aren't the heroes. At the end of the first lap, Fred Merkel is out of the race and Spencer isn't even in the top 50. Scott Gray is. He starts off at the very end of the first wave, and soon he’s in the top 20. Then he’s in eighth and still catching up. This is what motivates all racers, what makes them overlook the foggy Mississippi nights, the long drives and the endless hours of work. It's something in the racing, in overcoming all the odds to perform at your best.

But for Scott Gray, it wasn’t to last. In the infield on lap 10, another privateer with the same ambitions and visions cuts underneath Gray. They bump, they crash, they tumble. No more eighth place, no more personal best, no more Daytona. It's over and there’s nothing more to overcome.

When the dust cleared, Gray had broken his collarbone and smashed his Suzuki. While Spencer was cutting through the pack to win his first 200, Scott Gray was in the emergency room at Daytona Beach General. The total bill for the week in parts, pain and labor was enormous; the start money wouldn’t begin to offset it. Gray left Daytona with his arm in a sling, a destroyed motorcycle and a record that showed one disaster after another. The only thing left to do was what almost every other racer at Daytona would be doing over the next few weeks.

Scott Gray went home and started making plans for next year’s Daytona. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

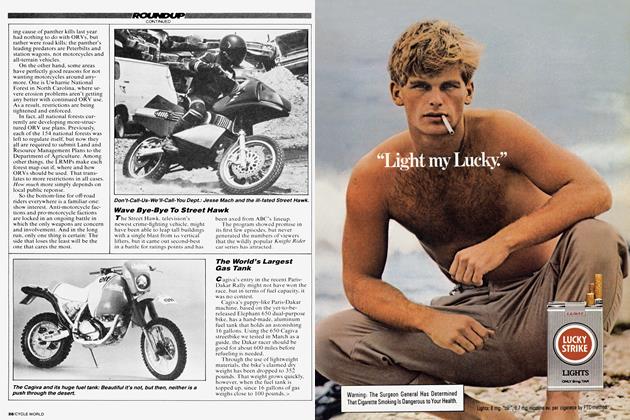

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985